Each country has its own system for categorizing and labeling wines based on the specific region it’s from. In historic winemaking nations like France, Italy, and Spain, there are strict rules that the wines have to follow in order to be included in one of the more prestigious designations. For example, Italy’s classification system includes several levels that the wine can be labeled under including Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT), Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) and the most prestigious, Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG). In order for a wine to achieve DOCG status the grapes must be grown in a very specific region and the producer has to follow the regulations denoted in the appellation law, which can range from farming practices to blend or aging requirements.

Since the restrictions are so tight in these classification systems, you usually know what to expect from a wine when you buy a bottle with that specific designation. We do things a little differently in the U.S.: Our classification system is broken down into specific American Viticultural Areas (AVAs), which denote the region within the U.S. that the wine is from. To be formally recognized as an AVA, a region must demonstrate geographic or climatic features that impact how the grapes are grown, which distinguishes it from other surrounding areas. Unlike under many European systems, there are no specific restrictions on what varieties can be used or how the wine is made in order to put the AVA on a wine’s label — only that at least 85 percent of the grapes are grown within that AVA.

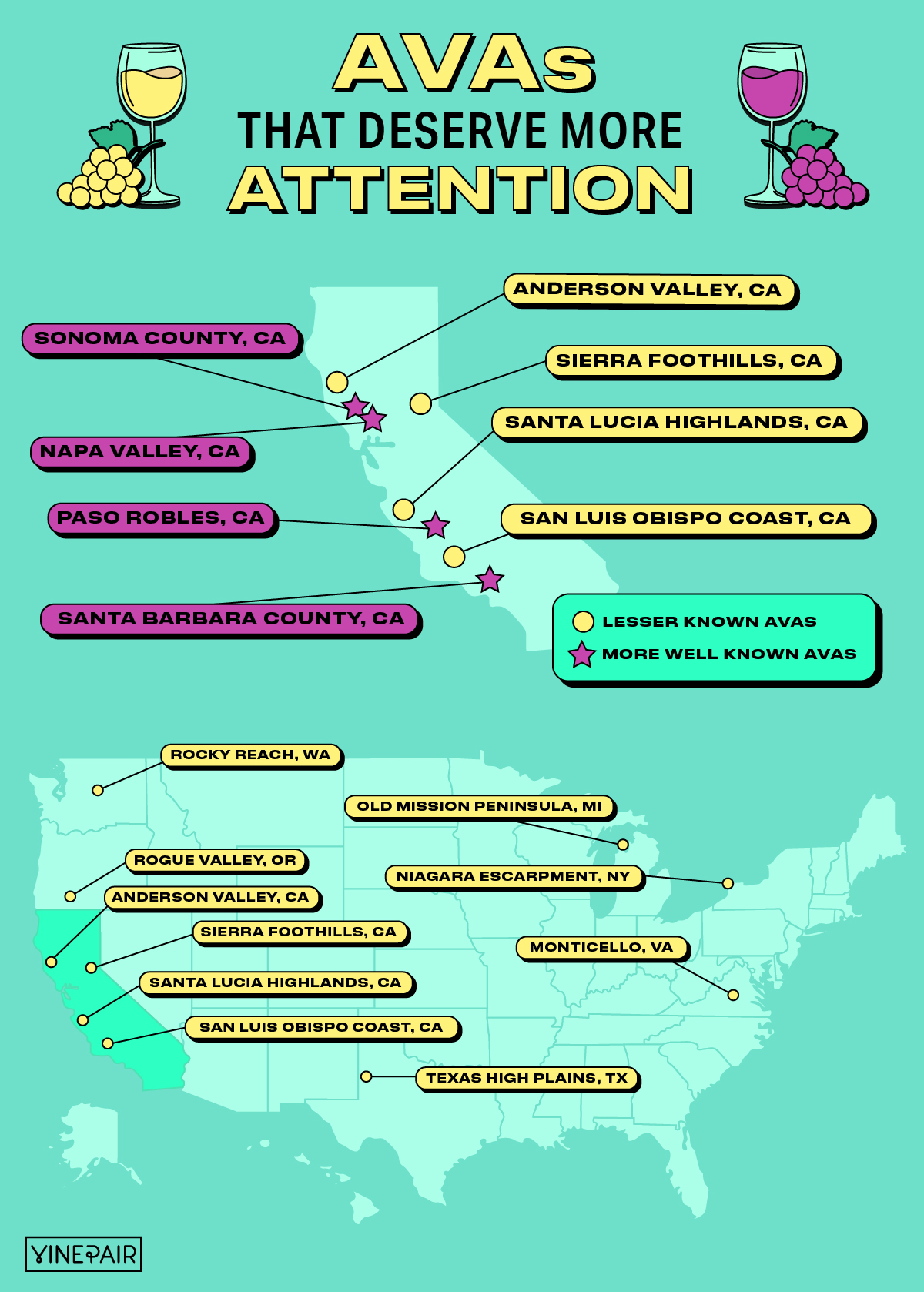

The AVA system receives some criticism for its lack of regulations and constantly growing number of additions, but its flexibility can help small wineries gain recognition and let consumers know where their wine is coming from. While prestigious AVAs like Napa Valley, Sonoma, and the Willamette Valley have achieved widespread fame for their outstanding quality, previously underappreciated wine regions like the North Fork of Long Island, Santa Barbara County, Paso Robles, and the Finger Lakes are now thriving having benefited from being recognized as distinct growing regions with their own specific terroir. So, what are the next AVAs to keep an eye out for?

Here are 10 AVAs that deserve more attention.

Anderson Valley AVA

When you go to pick up an American Pinot Noir, chances are you’re looking for a region known for high-quality bottles — think the Sonoma Coast, Russian River Valley, or the Willamette Valley. Well, Anderson Valley deserves to be ranked among the rest of this category’s major players. The Anderson Valley is a small area within the larger Mendocino County area, which lies just above Napa and Sonoma. Its location in Northern California and its unique position in a valley that draws in the ocean breezes and fog from the Pacific make it one of the state’s coolest wine regions. Therefore, cool-climate varieties — particularly Pinot Noir — thrive here. In terms of white wine, you can expect elegant Chardonnay as well as some less traditional expressions of Riesling and Gewürztraminer.

Monticello AVA

Monticello is often referred to in the context of history: It’s Virginia’s oldest AVA and named after the estate of famed wine enthusiast Thomas Jefferson. That said, it rarely gets the appreciation it deserves for the wines being grown there in this century. The growing region benefits from warm summers and the protection that the Blue Ridge Mountains offer from the wind, making it ideal for viticulture. While cold winters and springs present a threat to the vineyards, many producers have selected sunny sites with southeast exposure on the mountain slopes.

Monticello has had great success with popular grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay, and has also made a name for itself with stand-out Viogniers and Nebbiolos. Some producers to try include Barboursville, Pollak Vineyards, and Blenheim Vineyards.

Niagara Escarpment AVA

While New York regions like Long Island and the Finger Lakes have firmly established themselves in the U.S. wine scene, it’s time to pay some attention to the newest AVA in the Empire State. The Niagara name might have you thinking of Canada, and though this appellation is associated with Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula, this AVA is firmly rooted in New York. The other part of its name comes from a landform: an impressive limestone ridge that runs more than 650 miles through Ontario, New York, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The massive landmass plays an important role in the area’s climate, helping to trap the warm air coming off of Lake Ontario, which is necessary in the cool climate where grapes would normally struggle to ripen. Producers like Arrowhead Spring Vineyards, Leonard Oaks Estate Winery, Tawse Winery, and VineLand Winery aim to craft elegant cool-climate Chardonnay, Riesling, Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Franc in the region, but one should also keep an eye out for the delicious ice wines.

Old Mission Peninsula AVA

While Michigan’s AVAs aren’t exactly new — the Old Mission Peninsula AVA is the state’s youngest, and was granted in 1987 — many consumers are just beginning to explore the range of wines Michigan has to offer. Similar to those in the Finger Lakes, Michigan’s wineries benefit from glacially deposited soils and the warming “lake effect” from Lake Michigan, which turns a normally inhospitable area into a thriving pocket of viticulture. Surrounded by water on three sides, the Old Mission Peninsula has a maritime climate. As Michigan’s coolest AVA, it is at risk of the impacts of unseasonal frost. Expect cool-climate varieties like Chardonnay, Riesling, and Pinot Noir as well as some hybrid grapes like Chambourcin and Vignoles, which are currently seeing a spike in popularity among adventurous wine drinkers.

One standout producer is Left Foot Charley, which sources its grapes from local growers on the Old Mission Peninsula. The winery works with the typical grapes of the region as well as experiments with more unconventional grapes like Kerner and Auxerrois. If you want to stray even farther off the beaten path, check out Neu Cellars, where you will find delightful Riesling pét-nats and skin-fermented wines.

Rocky Reach AVA

Awarded in 2022 as Washington State’s 20th AVA, Rocky Reach exemplifies how the AVA system helps areas with distinct terroir differentiate themselves. Rocky Reach is located within the larger Columbia Valley region of Washington, but the area has demonstrated that it deserves independent recognition and allows for further appreciation of the complexity of Washington State as a wine region.

The defining factors here are the geology and the soil. Rocky Reach is the only site in Columbia Valley that diverges from basalt bedrock, and is instead composed of metamorphosed sedimentary and igneous rocks. These rocks are rich in silica and minerals like quartz and mica. Also, in addition to the typical sand and silt soils found throughout Columbia Valley, Rocky Ridge has cobblestones and gravels as a result of historic glacial floods. These points of differentiation all lead to the area’s distinct wine-growing terroir. The wines grown in this region — mostly red grapes including Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah — are all thought to have a special minerality as a result. Pick up some wines from Rocky Pond Estate Winery, a leader in the region, to see if you can taste the rocky soils yourself.

Rogue Valley AVA

Rogue Valley is both the southernmost and highest-elevation AVA in Oregon. The region’s climate is uniquely impacted both by its proximity to the Pacific Ocean and its placement at the intersection of three mountain ranges: the Cascades, the Coast Range, and the Klamath Mountains. Due to the variable climates and soils throughout the region, you can find a wide range of warm-climate wines from grapes such as Merlot, Tempranillo, Malbec, and Syrah. In areas with higher elevation and coastal influence, you will find more cool-climate grapes like Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Riesling. Sub-AVAs within the Rogue Valley, including Applegate Valley and Bear Creek Valley, help in denoting the different areas. Foris Winery’s Riesling and Gewürztraminer are great examples of the region’s potential for aromatic, cool-climate varieties. There are also some interesting biodynamic wineries in the area like Cowhorn and Troon Vineyard.

Santa Lucia Highlands AVA

With the growing demand for elegant, cool-climate Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in the U.S., it’s no wonder why producers are turning their attention to more regions with coastal influence. One of these areas is the Santa Lucia Highlands, an eastern-facing mountain range in the larger Monterey County. This AVA actually has one of the longest growing seasons in California due to the cooling breezes and fog provided by the Pacific Ocean. The wind actually reaches such high speeds that it slows the growth of the grapes and causes them to grow thicker skins. The long hang time on the vine leads to wines with fresh acidity and more complex flavors. Pinot Noir is king here, but watch out for some incredible examples of Chardonnay and cool-climate Syrah from this region, too.

San Luis Obispo Coast AVA

Speaking of the increasing appeal of coastal regions, California’s latest addition to the AVA system is the San Luis Obispo (SLO) Coast, which was appointed in 2022. The AVA cites its proximity to the Pacific Ocean as its defining feature, with 97 percent of vineyards planted less than six miles from the water. In addition to the ever-so-popular cool-climate Pinot Noir, Syrah, and Chardonnay, the region is experimenting with coastal expressions of Albariño, Grüner Veltliner, and Riesling. Make sure to check out the elegant wines from Scar of The Sea winery and Talley Vineyards.

Sierra Foothills AVA

The Sierra Foothills is not necessarily a new AVA, but as an often underappreciated region compared to its neighbors to the west (Napa Valley and Sonoma County), it remains a region for innovation and opportunity. The vineyards lie on the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range at up to 3,000 feet, creating an interesting terroir for vines in an otherwise hot region. There are a lot of old Zinfandel vines throughout the area, which contribute to some seriously complex wines. There are several sub-AVAs to pay attention to here as well, like El Dorado. The area’s name is a reference to the influx of inhabitants during the Gold Rush, when gold was discovered in the county in 1848. We have been impressed by a few great producers in the area this year, including Lava Cap Winery and Miraflores Winery. Producers like Forlorn Hope are also experimenting with uncommon varieties in the high altitudes of the Sierra Foothills like Trousseau, Graciano, and Muscat.

Texas High Plains AVA

The VinePair tastings department has been seriously impressed with Texan wines this year. While many of them are from Texas’s largest AVA, Texas Hill Country, the state’s second-largest AVA is one to watch. Texas High Plains is located in the High Plains area of the larger Great Plains, named for the area’s 3,500-foot altitude. While much of the state is considered too hot to grow grapes, the diurnal temperature variation this altitude allows for cools down the vineyards at night, slowing ripening. The region produces a large proportion of Texas wines, with many wineries across the state sourcing from this AVA. Popular varieties in the region include grapes that can stand up to hot weather like Cabernet Sauvignon, Tempranillo, and Grenache, and many wineries are having success with blends. Look for wines from C.L. Butaud, William Chris Vineyards, and Kalasi.

*Image sourced from Sergei – stock.adobe.com