No one knows for sure when Rossi’s Liquors opened on State Street in Chicago’s River North neighborhood. Suffice to say that this 7 a.m. tavern and bottle shop with the heavy metal door and curved green awning has been around for at least 50 years.

If I stand across the street, squint at the low-slung, whitewashed brick facade that houses the bar, then multiply it in my mind’s eye, I can get a sense of what this river-hugging stretch of Chicago looked like then — whenever then was. I’m following the instruction of historian Bill Savage, a professor of English instruction and academic advisor at Northwestern University. He tells me the neighborhood would’ve been all industry, rail, and newspaper production back then, which, naturally, “meant a whole lot of thirsty guys.”

As the Near North Side neighborhood around the bar evolved, trading factories and rail lines for swanky hotels and soaring office and condo buildings, Rossi’s ever remains a no-frills joint to pop into for a cheap, cold beer and a chat. These days the bar attracts as many hipsters and tourists looking for an “authentic” Chicago experience as it does the after-work crowd of tech company employees and the now post-industrial overnight shift workers from nearby hospitals and hotels. Being nonspecifically historic, plastered with incidental “decor” like randomly slapped-on stickers, old photos and signs seemingly plays to its advantage. As does the bracing dose of cheek one can expect from proprietor Dennis McCarthy and the bartenders, themselves the affable incarnations of the small framed sign hanging above the register that says, “cheer up f*ckface.”

“Places like Rossi’s have to be lucky and smart to survive,” Savage says. “But they also must be providing something people want or they would be shuttered. Rossi’s motto, about being there when you need them, is a two-way street: If people weren’t buying what they are selling — the booze and the ‘atmosphere’ and the attitude of ‘we are what we are; tough shit if you don’t like it’ — no amount of luck or brains would keep the doors open.”

Many of the 8,000 Chicago taverns in existence around the time Rossi’s opened have long since closed — casualties of the natural processes of cities: changing demographics, economics, and drinking habits; gentrification; and, in the case of the Daley mayoral dynasty, some hostile policy making. Now a little less than 900 bars remain. Many of them look worlds different — the motley offspring of the bar subgenres that first arrived post-Prohibition and now peddle every concept imaginable, from molecular mixology to shuffleboard.

Scarcity has an upside, though. This shrinking cohort of old joints represents something authentic that links their customers to what the neighborhood once was — whether real or imagined.

The ‘Stuart Little’ of Long Island City

The cocktail bar Dutch Kills is also a stout brick structure with an industrial door, set among kindred brick and clapboard facades. Standing across the street and squinting at this stretch of Jackson Avenue will create a similar “Stuart Little”-esqe feeling, if one breaks from mentally rebuilding the Long Island City of yore and looks up. Glass towers rise on all sides like glittering spaceships.

“Buildings are going up faster than you could imagine, and filled with… God knows who lives in these places,” says Shan Nicholson, a documentary filmmaker and Long Island City resident since 1979. “Literally you’re like, ‘I never thought this would happen in my lifetime.’ But what should take 50, 60, 70 years transpired in 10, and it’s still happening.”

On the whole, the story of Long Island City and the 14-year-old cocktail bar that Richard Boccato and the late Sasha Petraske opened there in 2009 shares few similarities with that of Rossi’s. One could plausibly even claim that Dutch Kills helped the gentrifying winds of change blow into this once-blighted area of northwestern Queens. But like Rossi’s, Dutch Kills represents a link to an authentic, increasingly scarce, slice of New York history all its own.

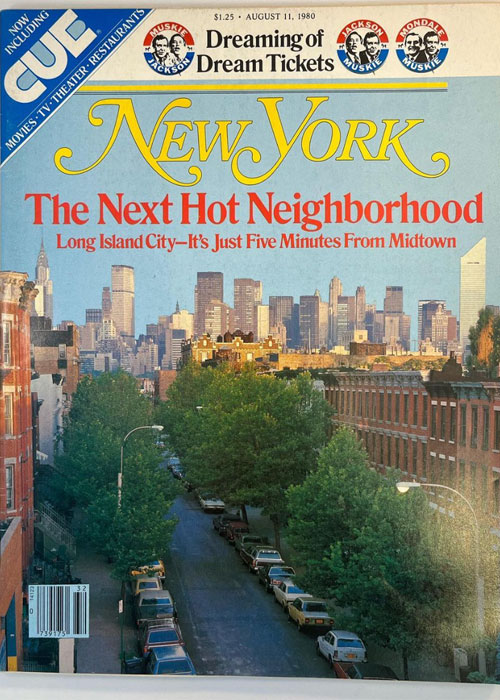

Like River North, Long Island City’s roots are predominantly industrial — dotted with small residential pockets housing blue-collar families. By the late 1970s the promise of space so close to Manhattan was already luring artists like Nicholson’s parents. In fact, a year after his family moved there, “New York” magazine featured Long Island City on its cover. “The Next Hot Neighborhood: Long Island City — five minutes from downtown.”

“It’s something that grows and mutates, by proximity of that original gentrification point to other cool places. So gentrification that starts on the Lower East Side … grows and goes over the bridge into Williamsburg. Then to Greenpoint and Bushwick, then Long Island City.”

“It took about 40 years for that cover story to come to fruition,” laughs Nicholson, who’s made such New York-centric documentaries as “Downtown Calling” (2009) and “Rubble Kings” (2015). “Growing up it was like an industrial wasteland, for the most part — some functioning factories, but also a lot of abandoned buildings. People stealing cars would, like, strip them in the alleyway. You know what I mean? Sometimes vans would roll up and doors would swing open and people just threw an old couch or fridge on the street. As kids, we were like, ‘Oh shit, let’s go play on it!’ It was part of the fun.”

Nicholson’s childhood friend Boccato often came from South Brooklyn to Long Island City “to play on the subway tracks, write graffiti, and break bottles — like the untamed wild youth we were,” Boccato recalls.

In his 20s Boccato moved to Long Island City, where he lived for eight years while cutting his teeth downtown at Petraske’s trailblazing, pre-Prohibition-style cocktail bars, Milk & Honey and Little Branch. Boccato’s apartment stood a few blocks from where Dutch Kills is now on Jackson Avenue, where rubber supply, auto transmission, and hardware stores formed the commercial backbone of an otherwise blighted stretch. The sole edifice that stood much higher than two stories was the Citibank building, which arrived in the ’80s.

“You’d see mattresses on the corners; it was not uncommon to see arson — all the textbook signs of urban blight that many of our city officials and agencies have since tried to eradicate,” Boccato says.

Writing’s on the Wall

Development had indeed arrived in the neighborhood, but it was concentrated along the waterfront on Center Boulevard. When Petraske asked Boccato if he’d like to open a cocktail bar in his neighborhood, the two briefly entertained the idea of opening the bar closer to the East River, on the already heavily saturated Vernon Boulevard, before opting to go off the beaten track. So in 2007 Boccato started building his bar on that rundown stretch of Jackson Avenue. Dutch Kills opened in May 2009, with similar — “maybe better” — cocktails as Milk & Honey, featuring hand-cut shards of crystal-clear ice, for half the market price so as “not to alienate our constituency,” Boccato says.

Nicholson told his friend this was crazy, of course — that “there’s nobody over here, there are no good buildings,” he says. “The Citibank building was the closest to any sort of activity, but it’s an office, so it’s dead after 5.” He recalls taking his now wife there on their first date: “She was like, ‘Where are you taking me? This place is shady!’”

“There was a community in Long Island City. Now people who come stay for five or 10 years; they don’t live here for generations and generations and raise families. That’s just lost.”

Yet the writing had long been on the wall for this future residential hotspot, much like other gentrification centers Nicholson has studied and made films about.

“It’s something that grows and mutates, by proximity of that original gentrification point to other cool places,” he says. “So gentrification that starts on the Lower East Side [the not so coincidental site of the original Milk & Honey], which was probably the big one in the late ’90s, grows and goes over the bridge into Williamsburg. Then to Greenpoint and Bushwick, then Long Island City.”

Dutch Kills quickly became a destination — less for the cocktail and food aficionados from Manhattan, who were “too lazy or too scared to come to Long Island City then,” Boccato says. First came the creatives, drawn to parties and art exhibits at MoMA’s PS1 in Court Square, not unlike Nicholson’s parents in the ’70s. The tourists and everyone else followed, until Boccato was serving a steady cohort of regulars. Meanwhile, many of the blue-collar families Boccato and Nicholson knew growing up moved away, bought out by developers taking advantage of friendlier rezoning. Entire blocks of clapboard and brick structures were razed to make way for soaring condo buildings. A Chipotle opened down the block from the bar.

“The problem is gentrification displaces people,” Nicholson says. “There was a community in Long Island City. Now people who come stay for five or 10 years; they don’t live here for generations and generations and raise families. That’s just lost. It’s hard for an average blue-collar guy to survive in New York. You can’t just have a normal type of job and live in the neighborhood, not in Long Island City, at least.”

Authenticity as Currency

Yet even as 80-story glass towers spring up all around him, Boccato, who rents, isn’t concerned about the bar’s future, largely because its status as an “authentic” neighborhood attraction lends coveted distinctiveness.

“The developers have taken pains to keep buildings like ours and those close to it, to create amenities for tenants — a bookstore and interesting restaurants,” he says. (Indeed, the bar has secured air rights to prevent building directly on top of it.) “So in that sense, we have a captive audience we never had. Things like that are due to a tremendous amount of luck but also foresight on the part of the developers who understand there’s less charm in something in the lobby of a glass tower than good old-fashioned brick and mortar with a steel door.”

“By going there, people are embracing something about the city that makes it unique and interesting, not just another chain in a shopping mall.”

Brains, luck and scarcity — especially when combined with owning one’s building or signing a long, favorable lease — offer a powerful kind of currency as big swaths of cities increasingly resemble playgrounds for the rich. It may partly explain why every time I call Rossi’s to request an interview with McCarthy, I get some version of “f*ck off” in reply — whether through incredulous refusal or lack of response. Savage assures me that this bodes well for the health of the bar, while keeping with its “tough shit” MO: “We don’t need your press!”

I still remember the first time I walked into Rossi’s around age 24 — having passed it a handful of times too intimidated to open that formidable metal door. Seventies rock blared on the jukebox; the crowd was a mix of old timers, hipsters, and tech bros and gals. I watched a few people grab beers from the cooler and pay at the bar before mustering the courage to copy them. Even then, the bartender gave me shit for not having cash. But said beers were blessedly cheap; friends and I crammed ourselves around one of the small tables where we camped out happily for three more rounds, shouting back and forth while we waited for our jukebox picks to play. Why had I waited so long to come here?

“By going there, people are embracing something about the city that makes it unique and interesting, not just another chain in a shopping mall,” Savage says. “What used to be here gets talked about way too much in these old places. On the upside, people new to the neighborhood will learn about it. It’s nostalgia for the old timers and excitement for the newbies.”

With $17 craft cocktails ($14 during Happy Hour), Dutch Kills never quite fit into the realm of a “third place” in the sense of being affordable to all, like a neighborhood tavern. But both joints occupy the shared space of linking new generations of city-goers to a near or distant past. Because Dutch Kills has indeed aged into the realm of being historic, as a bar built by a kid who grew up hanging out in the neighborhood, who knows its streets, who learned how to make craft cocktails from a legend at the start of New York’s craft cocktail renaissance. This seems to carry more weight now that many iconic cocktail bars that opened during the pioneering decade of 1999–2009 have since faded away.

“It’s an attraction that keeps with the integrity of the neighborhood,” Nicholson says. “It’s authentic New York history that you can walk into and have a great cocktail and great conversation; he really got it right with that.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!