Two years from now, it will have all seemed inevitable. You will want wine, and instead of going to your local brick-and-mortar store, you will log onto your Amazon Prime account, do a quick search, compare prices, glance at ratings, and order. It will be delivered to your doorstep.

For free.

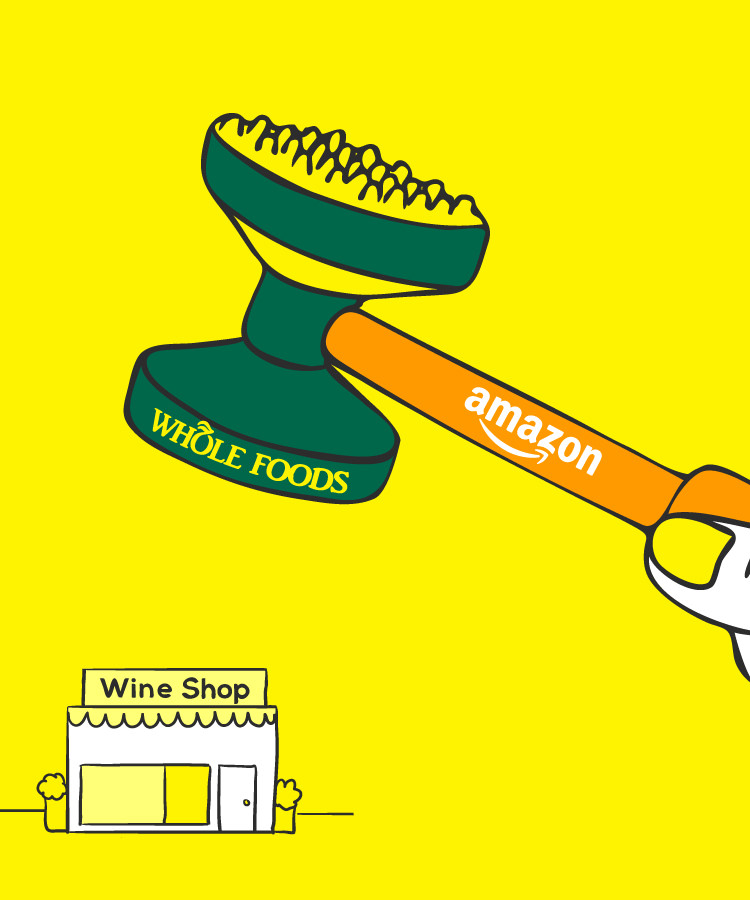

Industry observers and consumers see what some wine retailers fail to: Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods spells doom for small-scale wine shops.

In the next few years, brick-and-mortar wine stores will slowly become havens for the elderly, fringe radicals who insist on living their life “off the grid,” and hardcore connoisseurs whose need for small-batch, obscure regional varietals cannot be met by a corporate behemoth like Amazon.

Amazon + Whole Foods

As Scott Galloway, a professor at the NYU’s Stern School of Business and founder of L2 Inc., a business intelligence firm, put it on CNBC’s Squawk Alley shortly after news of the buy became public: “You just gave Amazon entree into the wealthiest households in the wealthiest urban centers in the world. This is a frightening day for every retailer that is not Amazon.”

(And yes: At this point, the reality of Amazon delivering wine right to your doorstep is still hypothetical in most places. We discuss the rings of fire it must – and has already begun to – jump through to make this a go across the country below).

Consumers have been gravitating toward online wine delivery for years. Online sales of liquor reached an estimated $614 million last year and reached an annualized growth rate of 11.7 percent over the past five years, according to market research firm IBIS. Apps like Drizly, Thirstie, Swill, and Saucey have been raising millions and expanding their reach. Delivery is available in virtually every city in America, often by virtue of partnerships between the operators and brick-and-mortar stores. The partnerships help everyone by padding the stores’ bottom lines and allowing the online delivery services to bypass different state regulations on distribution vehicles and purchasing licenses. These services charge a fee, of course, most of the time in the single digits.

The news that Amazon was buying Whole Foods for $13.7 billion makes an accelerating trend seem like an unavoidable reality, with much further-reaching consequences.

Prime Wine

Amazon will essentially bypass the maze of app-store partnerships with Whole Foods, essentially created a built-in distribution center that will allow it to legally deliver wine across the country. And if Amazon follows its current Prime model, delivery will be … free.

Now that Amazon will make it possible for people to order a bottle of $16 Pinot Grigio (that sells for $18 at their local) along with diapers and books? Game changer.

“As someone who has utilized Amazon Prime for six years, I’d love to finally make the move from diaper delivery to wine and beer delivery,” Tara Gutman, an attorney for Geico and mother of two school-age boys tells VinePair. “I would certainly go to the store for some items, depending on Amazon’s stock and price. However, being able to have good wine delivered would be an invaluable service. These days there isn’t always time to get everything done and knowing good wine could be waiting at your doorstep when you arrive home from a long day would be lovely.”

As most economists will tell you, women hold the nation’s purse strings. Researchers estimate that women make 85 percent of the purchasing decisions in the U.S.

And as Tara noted above, women (and men) seem busier than ever these days, and look to Amazon Prime as an easy way to cut through the time-sucking tasks of schlepping and shopping. More than 70 percent of American households with annual incomes of $112,000 or more were Prime subscribers as of 2016. About 40 percent of all Prime subscribers shell out $1,000 per year on Amazon.

In a recent podcast, Galloway predicted that Amazon will increase its average household spend on Prime with this acquisition and others, up to roughly $7,000 a year, and in the process, wipe out mom-and-pop and big-box retail stores by the thousands.

“The winners are consumers and Amazon shareholders,” he said. “But the losers are the retail ecosystem, which includes 11 million cashiers, which includes the 40 million households that have a share of Gap or Walmart. You’re effectively seeing this giant sucking sound out of the entire retail ecosystem into a small number of players.”

While Tara and other consumers cite convenience as a factor, oenophiles in geographically challenged or remote regions are slavering over the expected colossal selection and free delivery. There are challenges, to be sure, and Amazon may need to get creative in order to have this colossal selection, but if anyone can figure it out, they can. (Many renowned retail stores and wineries offer to deliver high-caliber wines, but there’s always a steep delivery fee. And wine-of-the-month clubs sometimes offer free delivery, but the selection rarely meets cork dork standards).

“I will absolutely order from Amazon if they find a way to deliver wine within proper temperatures in Florida,” said Laura Laytham Zaki, a Manhattan-to-Florida transplant, media consultant, mother of two, and a shameless lover of stupendously pricey Bordeaux. “The wine selection in Florida stores is abysmal. I’d never go again.”

According to a recent study from 1010data, of the consumers who shopped more than once at a Whole Foods over the past year, 81 percent were members of Amazon Prime. And Amazon Prime members are big spenders at Whole Foods. Regular WF shoppers who are also Prime members spent an average of $1,371 at the store, $306 more than non-Prime members. In addition, Whole Foods fans are more likely to shop for groceries (10 percent use delivery) than Kroger or Albertsons shoppers (5 percent and 6 percent, respectively, use delivery).

Amazon began rolling the wine delivery program out in earnest months before the acquisition of Whole Foods was announced. In March, Amazon announced that its Prime Now offered one- and two-hour delivery for wine and beer in Cincinnati and Columbus. Popular brands like Chateau Ste. Michelle, Bud Light, Great Lakes Brewing Company, Rhinegeist and Veuve Clicquot were available. Two-hour delivery is free, one-hour delivery is $7.99. Delivery is also available in Seattle and Washington.

Where We Are Now

So when will you be able to order your wine on Prime? Here’s where things stand now:

In June, Amazon announced its intention to buy Whole Foods for $13.7 billion. The size of the deal – 10 times bigger than any other acquisition they’ve made – was enough to raise eyebrows.

Under the terms of the deal, Whole Foods Market will continue to operate stores under its own brand and “source from trusted vendors and partners around the world,” the company said. John Mackey will stay on as CEO.

The transaction is expected to close this year.

In fiscal year 2016, Whole Foods had sales of $16 billion with more than 460 stores in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

Amazon, of course, has a grocery biz in place. In 2007, it launched a grocery delivery system called AmazonFresh. While the company has attempted to modernize the process of food delivery and sorting via machine learning (programming robots to decipher the difference between moldy and fresh food, drone delivery, etc.), the going has been tough.

Amazon has about 100 million square feet of space in its fulfillment and data centers. About 3 million of that is dedicated to AmazonFresh and Prime Pantry grocery programs. Whole Foods has more than 1 million square feet of warehouse space just for distribution to its markets. So Amazon just increased the reach of its grocery and beverage arm by one-third.

There does appear to be a step missing in Amazon’s use of Whole Foods to leapfrog into the business of selling limitless wine options to Prime customers. Amazon will still be constrained by laws that vary by state limiting the sale and transport of wine, and the limits of a particular Whole Foods’ current wine selection. For example, Whole Foods has one location in Iowa. Yes, they could use that one location to ship anywhere within the state, but will the selection meet cork dork standards? Amazon has not shared its wine marketing plans with the world yet, but one could speculate that it will ensure that every Whole Foods carries a core base of highly regarded, nationally available wines that oenophiles like. In other words, relatively big-batch wines that have earned Wine Spectator’s stamp of approval. But that’s just speculation.

Also worth noting, Amazon has been lobbying Washington for years on a number of subjects, including its liquor-shipping laws. Last year, it spent $11.3 million on lobbying. Compare that to Anheuser-Busch InBev SA, the beer industry’s biggest lobbyer, which only shelled out $5.7 million.

Combining Whole Foods, with its penchant for sensing and marketing to the zeitgeist currently occupying the wealthiest class of consumers, and Amazon, with its talent for disrupting and then revamping new markets, even with only a sliver of the market and at least one big question mark regarding the supply chain, they’ve created a powerful force in the market that is making competitors – from big-box stores, to mom-and-pop wine shops, to farmers – very nervous indeed.

Courting Small-Batch Cork Dorks

Amazon even appears to be courting the very cork dorks who might eschew Amazon’s selection on principle. One winery, King Estate in Oregon, sees Amazon’s reach as a huge opportunity to reach oenophiles it never could have marketed directly to before.

“We approached Amazon to develop a wine for them specifically,” Jenny Ulum, senior director of communications for the winery, tells VinePair. “We created a sub-label, King Vintners, to showcase distinctive growing regions in the Pacific Northwest. We will be launching five brands and each one will highlight a different growing region in Oregon. The goal is to bring the Oregon style of wine to a national audience, and we loved the idea of working with Amazon to sell it directly to consumers.”

The debut collection – dubbed NEXT – includes a $20 Pinot Gris, a $30 red blend and a $40 Pinot Noir. The initial run was about 1,500 cases per varietal. Across all of its brands, King produces between 350,000 and 400,000 cases per year, so while this only constitutes 1 percent of their production run, King is “thrilled” to get their wines to consumers who may not have been able to access them otherwise, Jenny says. The brand launched in June and sales have been fantastic so far, she says.

Still. While the wine market may be full of thirsty moms living the 9-to-5 baby juggle struggle, many of them are avowed wine snobs who aren’t going to trust their precious snifter of sanity to a bot.

“I would utilize both,” said Martha Fitzgibbons, a marketing director and mother of two. After a long day at the office followed by a crowded commute from Manhattan to New Canaan and the rigors of putting a toddler and preschooler to bed, Martha definitely deserves a glass of bubbly, no matter how it arrives. “For things I have been drinking a long time and know I like I would be inclined to sometimes order from Amazon,” she said. “What the local wine store brings is the chance to find something new. I would be more likely to trust them than a suggestion for Amazon. Not sure algorithms can replace actually trying the wine.”

Astor Wine & Spirits, for one, isn’t flummoxed at all by the news. Astor is one of the largest and, perhaps more importantly, highly regarded wine stores in the country. And yes, they’re online.

“A huge part of our business is shipping wine to Seattle or California,” Lorena Ascencios, the head buyer for Astor, explains. “We’ve been doing it for 15 years at least.” (Shipping is free over a certain threshold within New York, but they do charge to ship elsewhere).

But their established online business isn’t the reason Lorena finds little to fear in Amazon’s move online.

“There is no way Amazon can replicate what we have built,” Lorena says. “We don’t stock Yellowtail or any of the other large commercial wineries that do big volume but aren’t high quality. We love working with small producers because they’re interesting and often far superior to many larger-scale wineries. Often, we’ll just buy 25 cases from a winery. Currently, we carry 3,000 different wines, 2,000 of which are smaller producers that are hard to find elsewhere. We have been purposefully skewing our selection to be artisanal and we’ve been thriving.”

Lorena argues that Amazon will never be able to specialize to the degree that a smaller, more nimble store like Astor – with highly trained wine professionals on staff – can.

But more importantly, she believes that Amazon faces a logistical issue that a company relying on machines will never be able to overcome.

“What do they do if a wine is corked? Will they even know?” Lorena asks. “We are constantly sampling and testing our wines to make sure they are of the highest caliber. We have winemakers in every day to hold tastings and talk to our customers. That helps us, the customers and the wineries. Being able to touch, taste the wine, speak with the maker? You simply can’t replicate that online.”

The Inevitable

Shortly before announcing the acquisition of Whole Foods, Amazon released a promotional video advertising a $20 gadget called the Dash Wand. In the video, a middle-aged couple wanders around their beautifully appointed kitchen chatting with Amazon’s voice assistant Alexa. They’re preparing – as rich white middle-aged people do – for a fabulous dinner party the next day.

Rummaging through her fridge, she finds shrimp. She requests a recipe and then orders the ingredients she’ll need to complete her dish. While cooking the meal on the night of the party, she realizes she finished up her white wine. Whoops! “Order white wine from Prime Now,” she intones calmly.

The vaguely Orwellian video, in addition to being somehow spooky and boring at the same time, seems prescient.

Retailers like Astor Wine & Spirits – one of the most beloved and well-established stores in the world – are probably safe, just like indie bookstore juggernauts like The Strand still are, despite the fact that Amazon’s move into selling books single-handedly revolutionized (many would say decimated) the brick-and-mortar retail market. But everyone else? They should, as Galloway pointed out, be very frightened indeed.

It’s prime time for Amazon wine.