Depending on your age and tolerance for prerecorded laugh tracks, the name “Cheers” either brings to mind a much-beloved barroom sitcom that launched legendary actors’ careers, or a commercial-crammed network show that your parents watched before you (and Netflix) were born.

What it probably doesn’t make you think about are grotesque robots and the United States Supreme Court. But “Cheers,” which aired on NBC from 1982 to 1993, inspired maybe the oddest gimmick in bar history and one of the strangest cases in American legal annals.

In September 2000, after seven long years in litigation, Wendt & Ratzenberger v. Host International & Paramount Pictures finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court. At stake: whether a baker’s dozen airport bars in places like Charlotte and Cleveland could continue to have the animatronic likenesses of George Wendt and John Ratzenberger sitting on their stools, cracking jokes to bored business travelers and flummoxed frequent fliers.

Of course, Wendt and Ratzenberger were better known to television viewers as Norm and Cliff; and these cheesy airports bars were meant to resemble the iconic “Cheers” set.

You see, in the early 1990s, the height of “Cheers”’ popularity was such that co-producer Paramount decided to create an unprecedented, justice-system-stumping partnership. The resulting facsimile bars that featured the ghostly apparitions of TV viewers’ favorite “Cheers” regulars would appear in airports from 1991 to 2001.

But their mere existence speaks to a country that was spreading its literal and figurative wings. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, airfares were finally becoming cheaper and more accessible, bringing American travelers off the interstates and onto the tarmac in massive numbers. The airports’ desire to provide quality amenities for travelers was likewise improving. The problem was, airports didn’t quite know what travelers truly wanted and, early on, were, for lack of a better phrase, “throwing shit against the wall and hoping it stuck.”

These Norm and Cliff animatronics were goofy, kinda freaky, and charmingly low-tech by today’s standards. Still, the ghosts of “Cheers”’ most famous barflies haunted airport terminals for a full decade, offering questionably witty banter and a vision of our tech-obsessed, frequent-flying, up-in-the-air futures. And then, just like that, they were gone and are now almost completely erased from history.

*

In the early 1990s, Paramount was licensing out “lots of film and TV for ancillary usage,” Tom McGrath explains. He was the executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Viacom Entertainment Group at the time. (Viacom acquired Paramount in 1994.)

Paramount licensed the “Cheers” name to retail products like Bloody Mary mix, and to Vegas slot machines. It also issued a merchandising license, in 1989, to the Bull & Finch Pub in Boston, whose exterior had long been used as an establishing shot for the TV series.

By 1990 the bar was attracting half a million tourists a year, enabling owner Thomas Kershaw to open a ground floor gift shop. He sold “Cheers”-branded T-shirts, shot glasses, and ashtrays. Those products and more were bringing in some $3.5 million per year, about the same amount of revenue as the bar’s food and drinks.

Something was clearly working. Where some might have seen just a television-theme restaurant, McGrath saw greater possibilities. “Only a handful of adult-oriented properties can really make any money,” McGrath says. “’Cheers’ wasn’t a James Bond or ‘Star Trek,’ of course, but being set in a bar, we saw the potential for some opportunities.”

Luckily, at the same time, “there was a sea change going on in airport environments,” Sam Novack tells me. “The late-1980s was the first time you started seeing major food brands like Pizza Hut and Taco Bell adding airport locations — and generating more revenue than their street-side locations to boot.”

At the time, Novack was the vice president of concept development for Host International, a Delaware-based Marriott subsidiary and then-largest distributor of airport food, beverage, and merchandise worldwide. (Today the company is known as HMSHost.)

“[Host] had asked me to take a look and see what I could do with the adult category,” Novack says, “But there was really no specific adult beverage brands that had the awareness that these food brands had.”

Except “Cheers.” In 1990, “Cheers” was at the height of its popularity, in the eighth season of its 28-Emmy- winning, 11-season run on NBC. Novack had been negotiating a merchandising deal with Paramount to sell “Cheers” gear in Host’s airport gift shops. Why not develop a “Cheers”-based bar concept, too?

And so they did. The first “Cheers”-themed bar debuted in February 1991 in the J.M. Davey Terminal of Detroit Metro Airport. A second one came to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport a week later. (“In airports it’s an opportunistic business,” Novack says of the decision to launch in two decidedly secondary markets. “If an opportunity was available, that’s where we took advantage.”)

In a June 1990 statement announcing the venture, Francis W. “Butch” Cash, a teetotaling Mormon and then president of the Marriott Service group, issued a statement: “’Cheers’ has become the quintessential neighborhood bar and that is the atmosphere we want to create for the traveling public in these new bars and lounges.”

To accomplish this metaphysical feat, Novack spent a year on the Paramount lot, working with the sitcom’s set designers to create airport locations that would look exactly like the “real” “Cheers” bar. They outfitted both spaces with a signature square bar surrounded by round, no-back stools. On their walls, a framed Red Sox jersey once “worn” by Ted Danson’s Sam Malone character. Near the entrances stood an iconic cigar-store Indian and a Wurlitzer jukebox. Staff was even required to pass an acting class, perhaps even affect a “Bawston” accent, which they would use to perform for customers.

“Everything here in the bar was meant to remind the American traveler not of home, but of a series that appears each week on television,” wrote Bob Greene in a November 1992 Chicago Tribune review of the Kansas City location. The menu continued this schtick, with items named after the characters, like Sam’s Submarine Sandwich, Woody’s Polish Hot Dog, and, of course, steins of Norm’s Big Brewski. That was great for Paramount, as it got a percentage of food and beverage sales at each location.

“And why would a traveler possibly want to step into a TV series?” asked Greene.

Because, as Host spokesman Richard L. Sneed explained to him, “People are sitting at home when they watch ‘Cheers.’ So the characters in the ‘Cheers’ barroom become a part of many Americans’ families.” This was, according to Greene, “art imitating life imitating art imitating life, on into infinity.”

*

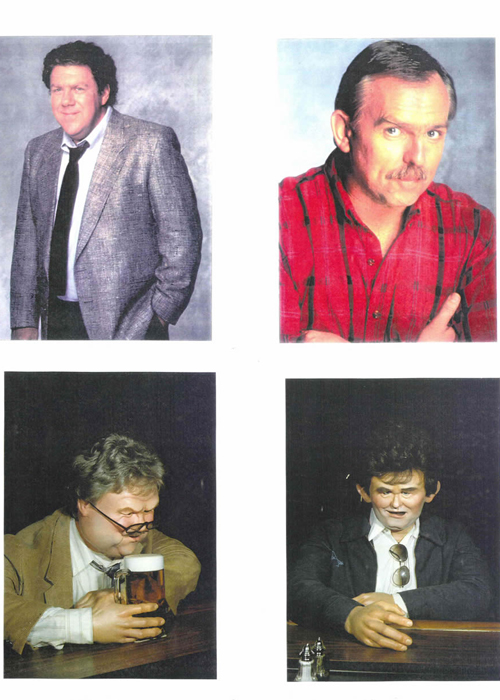

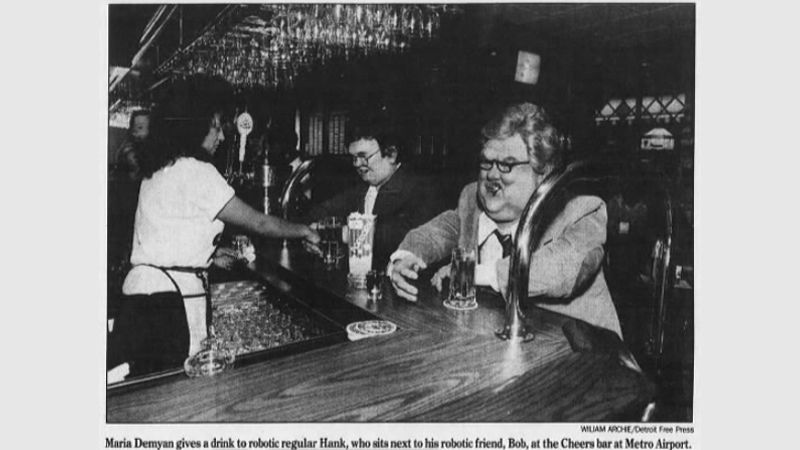

With, of course, one distinct, if not completely insane difference: Bob and Hank.

Two oversized, animatronic beer guzzlers who looked like warped versions of Norm and Cliff were commissioned to belly up to the “Cheers” bars using then-cutting-edge technology. They were called Bob and Hank because, well, naming them Norm and Cliff would have probably destroyed any legal footing.

“I was approached by a company out of New Hampshire who developed these kind of animatronic things for arcades and theme parks,” Novack says. “So I said, ‘Let’s give it a shot and see what happens.’”

Novack hired a Hollywood screenwriter to draft a script, some 30 lines of banter for the two robotic clods sitting at the end of the bar. Those pre-programmed conversations included such bon mots as:

HANK: “Didn’t the doc tell you to watch what you eat?”

BOB: “I am. I’m watching to make sure I don’t eat anything healthy.”

Whenever a customer sat near them, the animatronic characters would spring to life. Bartenders could also intentionally get the pair yapping if they were particularly swamped with drink requests and needed to create a diversion.

“[T]hey sort of slump forward at the bar, and then every few minutes they sit up straight, look at each other and have jovial conversations,” Sneed remarked in 1992.

It was like some Chuck E. Cheese from hell, where the characters come off the stage and loudly occupy coveted space in a packed layover bar. When the bar got busy or space crowded, the characters on the stools would “crack wise,” wrote Entertainment Weekly’s Ty Burr, “under the apparent assumption that drunks will watch anything.”

Apparently, that assumption was correct.

The Detroit and Minneapolis-St. Paul locations were huge hits. By January 1993, Bob and Hank were being replicated at airport bars in Cleveland, Kansas City, St. Louis, Anchorage, and, oddly, Christchurch, New Zealand. Additional locations eventually popped up in airports in Washington D.C., Boston, Las Vegas, Savannah, Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky, Memphis, and Vancouver.

“Most airport bars are just anonymous watering holes where people simply waste time while waiting for their flights,” Sneed said. “People feel like strangers in most airport bars. Here, they feel like they’re somewhere they’ve been before.”

Even if that “somewhere” was inside a TV set, it clearly worked — each location was doubling revenue from the airport’s previous tenant.

Sadly, there are no photos of the robotically-rendered duo on the internet. This was a pre-Instagram age, of course; searching the stacks for historical Bob and Hank coverage finds only one old local news report out of New Zealand. In it, a Kiwi bartender admits he opened up one morning and immediately heard voices inside — his first thought was he had locked some customers in overnight.

(To me, that would have been better than what he actually had to deal with every single day of his bartending life.)

“The animatronics were cute,” counters McGrath.

Really? Not creepy and annoying?

“People were only there for limited amounts of time,” McGrath says. “It’s an airport bar. If you were there for a long time like a normal bar it would be repetitive and annoying. Just passing through, stopping for a drink, it was fine.”

Fine, that is, to everybody but George Wendt and John Ratzenberger, who had never agreed to be Bob and Hank in the first place, and certainly weren’t compensated for it.

“It’s our contention that the license from Paramount does not address bringing in robots that take on these characters,” the actors’ lawyer T. Patrick Freydl said in January 1993, just a few months before 84.4 million people watched the “Cheers” series finale. “We’ve had ongoing discussions with them about this, and now this is the next step.”

That next step was to file suit in the Central District Court in Los Angeles against Host International. Amazingly, the actors didn’t win. While local California law gave performers the rights to control their images, federal copyright law gave the studios legal rights to use the characters they created. Thus, Paramount Pictures successfully argued that it, not the actors, held the copyright to the visages of “Norm” and “Cliff” and could use them as they pleased.

“This is a huge issue for Hollywood,” another of the actors’ lawyers, Dale Kinsella, said. “If a studio acquires the right to license an actor’s image cloaked in the outfit of the character, then Warner Bros. could use Harrison Ford’s face to sell cigarettes or beer as long as he was dressed as Indiana Jones.”

After a series of appeals, by October 2000, this now-landmark case had reached the United States Supreme Court. The highest court in the land, in turn, rejected Paramount’s claim. Wendt and Ratzenberger were finally free to bring their lawsuit in front of an L.A. jury. By June 2001, Paramount settled, ending a decade-long legal battle.

*

By this point, the airport “Cheers” bars were beginning to shutter anyway. Not because of the lawsuit; the fervor for them had simply petered out. A decade is quite a long time for any airport bar to exist, Novack explains, especially one based on a long-finished sitcom. By then, airports had started moving into higher-end fast casual and even fine dining. The most popular sitcom on the air in 2000 was “Friends.” (And no one wants a Ross animatronic.)

Kershaw, ever the entrepreneur, opened a second outpost of his “Cheers” bar in Boston in 2001; a Piccadilly Circus location appeared in London around that time as well. In 2002, Kershaw’s Bull & Finch was officially renamed Cheers Beacon Hill.

McGrath and Novack moved onto bigger and better things, too. The former had even greater licensing success by spinning off Forrest Gump into the Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. The chain currently has 42 locations around the world. McGrath also went on to win one Emmy and seven Tony Awards for such shows as “Hair” and “War Horse.” Novack is now an executive with Sammy Hagar Restaurants, which counts six Cabo Wabo Cantina locations in North America, including one at, yes, Las Vegas’s McCarran Airport.

To people besides McGrath and Novack, though, the airport “Cheers” bars remain a vague memory. A memory where you’re trying to drink a Bud Light before your boarding call and creepy robots are hollering over you, “Hey, Woody, a refill and some more pretzels.” A memory that probably seems like a nightmare. A memory of one of the strangest gimmicks in bar history. A memory that, though it seems hard to believe, actually worked! As Novack tells me:

“You know, I’ve really never heard of animatronics being done before or since at any other bar.”

Cheers to that.