Through a fortuitous series of work-related bookings in the second half of 2022, I’m about 14,000 points away from AAdvantage Gold status on American Airlines. Of course, with the deadline only two months away and insufficient work travel (or compulsion to open another credit card) to reach it, I’ll likely watch my chance at premium cabin upgrades slip away from the middle seat in row 28, knees pressing into the seat in front of me as I sip $10 industrial Merlot.

Calling economy airline travel abysmal feels increasingly like an understatement each time you find yourself in the irritable tin of sardines that is coach. Seats have shrunk, legroom reduced, and more of the services that were once standard have become chargeable extras. Aside from a few exceptions, drinking tends toward well liquors and commodity beer and wine.

Meanwhile, if you’re flying first class on, say, Emirates Airlines, as of this summer you can partake in vintage Dom Perignon and all-you-can-eat Persian caviar, in possibly the most unrelatable “bottomless” deal ever unveiled. The airline has also secured exclusive rights to be the sole carrier serving Moët & Chandon, Veuve Clicquot, and Dom Perignon onboard. That’s on top of interior upgrades, including more, and roomier, premium economy seating — yet another rung for the non-wealthy, non-business traveler to climb.

How did we reach this glaringly lopsided state of affairs? It’s not as if we suddenly lost our taste for the airborne piano bars, carving stations, or Don the Beachcomber-themed flights that defined the glamorous Jet Age. In fact, a lesser-known combination of factors conspired to make coach all but intolerable, starting with the deregulation of the American airline industry in the 1970s, which freed up competition and fed the burgeoning economy class. But perhaps the most consequential development of that era was the introduction of a new currency, frequent-flyer miles, which exploits consumers’ insatiable penchant for freebies in the guise of rewarding loyalty. Turns out, we’ll pay almost anything — and even sacrifice comfort and the pleasures of palatable food and drink — to get a free flight.

The First Taste of Luxury

The first-ever alcoholic drink served in the air was in December 1783, hovering above French soil in a hot air balloon designed by brothers Jacques-Etienne and Joseph-Michel Montgolfier. A physicist named Jacques Charles popped a bottle of Champagne and poured a glass for fellow passenger Nicholas-Louis Robert to toast the balloon’s pioneering ascent. This is according to Richard Foss, journalist and author of “Food in the Air and Space: The Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies.”

One could argue that this first in-flight service set the precedent for lavish tippling in the skies, but it merely reflected the privilege of those invited to fly from the outset.

“The first people to fly at all were scientists and aristocrats,” Foss tells me. “These members of the cultural elite expected to live as close as possible to the way they lived on a typical day. So of course they’re going to take china and fine food and Champagne up with them. What else would they do?”

Passenger air travel didn’t begin in earnest in the U.S. until the mid-1920s, after the Postal Service turned over airmail carriage to contractors, which would end up being the commercial airlines as we know them. Airlines in those days made all their money transporting mail, so they carried very few passengers, and tickets were expensive. They offered one cabin and one style of service, which was pretty basic.

Booze was illegal on domestic flights, due to Prohibition. But people found ways, traveling with hip flasks or sneaking liquor into bottles with medicine labels, claiming it was tonic for their nerves when confronted. And who could blame them?

“People were, frankly, being bounced around in the sky in the 1920s and ‘30s; air sickness was a problem,” says Bob van der Linden, curator of Air Transportation and Special Purpose Aircraft and a supervisory curator in the Aeronautics Department at the National Air and Space Museum. Aircraft were loud and barely broached 1,000-feet elevation, making flights unnervingly turbulent as they contended with competing up and down drafts.

The introduction of aircraft like the DC-3 in the mid-1930s changed everything. Their pressurized cabins could carry more passengers faster, farther, and in more comfort at higher elevation. Still wary of the patchwork of state laws in effect post-Prohibition, U.S. carriers didn’t offer drink service in American airspace until the late ‘40s, when alcohol became a major differentiator for the growing commercial airline industry.

Alcohol as a Marketing Gimmick

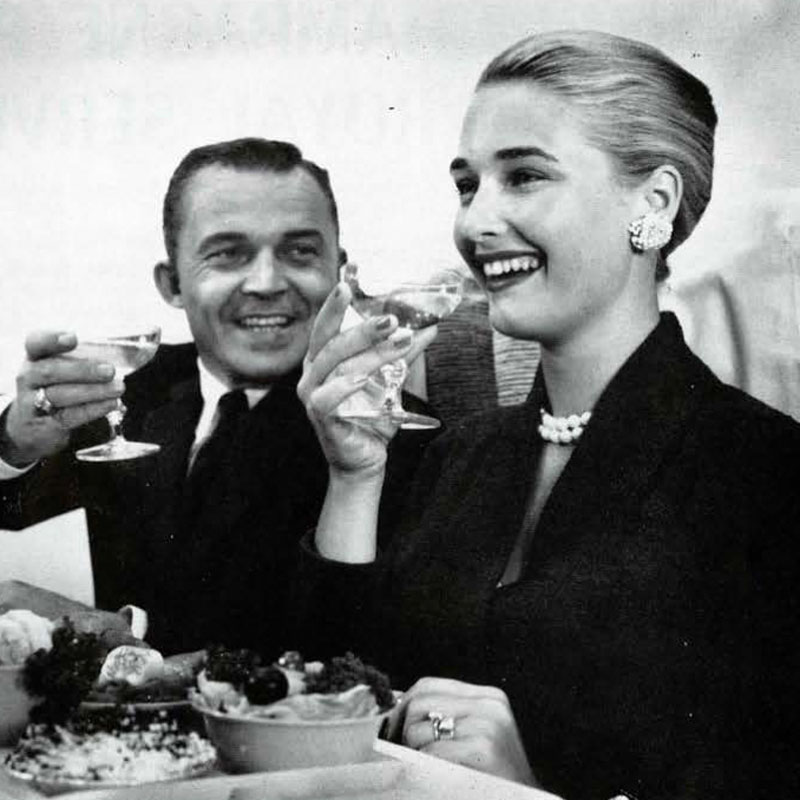

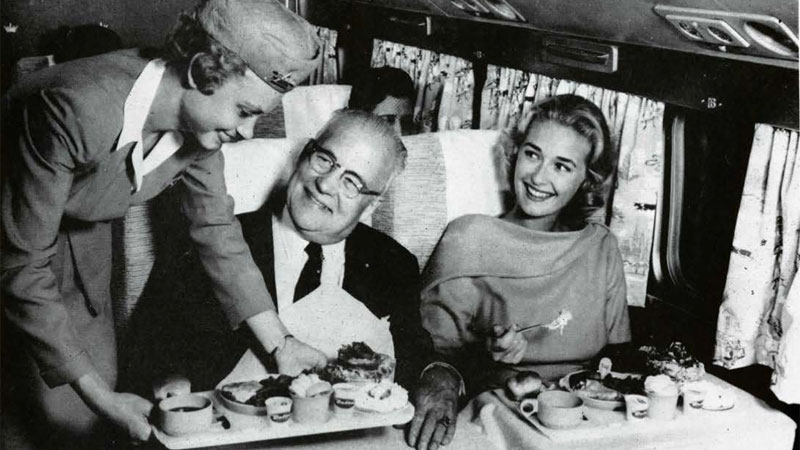

The Civil Aeronautics Board controlled ticket prices and seating plans since the first days of commercial aviation, meaning airlines were instead forced to entice customers with deluxe amenities, like coursed meals and free-flowing alcohol — a.k.a. the best available in-flight entertainment in the pre-screen era.

“Because airlines owned their own kitchens, they were afforded a high degree of individuality,” Foss says. “Alcohol was an aspect of that. In fact, some carriers advertisements featured pictures of people pouring cocktails on flights.”

Pan Am rolled out vast food and drink menus with coursed meals and a wide range of fine wines, served on proper dinnerware. Delta Air Lines’ Royal Service featured free Champagne, and afternoon canapes and cocktails passed out by three — instead of the usual two — flight attendants. Then-novel mini booze bottles were handed out like Tic-Tacs, goading a generation of collectors who took them home as souvenirs, often nicking extras off the roving drinks cart.

Silly, booze-soaked themes proved profitable. Stuck with aging DC-3 aircraft in 1960, New York-based Mohawk Airlines outfitted them to look like old rail cars with gold-filigree wallpaper and lace headrests. Stewardesses dressed as dance hall ladies doled out free beer, cigars, and pretzels to passengers. Two years and over 31,000 cans of free beer later, the airline earned enough money to buy new aircraft.

With the onset of the Jet Age and rising disposable income of Americans, airlines leaned into the sense of wonder and luxury associated with air travel. When ever-innovating Western Airlines introduced routes to Mexico, flights featured pseudo-Mexican fare and Margaritas. Continental Airlines tapped the soaring popularity of Polynesian-style tiki bars with Don the Beachcomber-themed in-flight service, complete with Mai Tais and Dungeness crab with tropical fruit and curried vegetables.

Aircraft innovation played a big role in the increasing creativity, with cabin configurations and in-flight service. The 747 could carry some 400 passengers, two-and-a-half times more people than the 707.

“Initially, the airlines thought they would attract people by putting amenities on planes,” van der Linden says. “So a lot of them put in lounges with bars. The Boeing 377 Stratocruiser had a spiral staircase leading to a downstairs lounge with a cocktail bar. And American Airlines, shoot, they put in a piano bar — with an aluminum piano, which must’ve sounded horrible.”

Alas, the lounges and piano bars proved short-lived, as did the 747’s domestic flights. The giant aircraft — moved to longer, trans-Pacific flights — was quickly supplanted stateside by smaller DC-10s and DC-11s.

More importantly, van der Linden notes, “airlines realized that as nice and comfy as a lounge and bar were, they’d make a lot more money replacing that with seats and paying passengers.”

Turning Seats to Dollars

The concept of economy class first emerged in the 1940s with so-called coach services, which were offered on separate flights that made more stops or carried freight or mail as well. It wasn’t until the mid-’50s that two-class cabins became standard on larger airlines. But they weren’t very popular. The number of U.S. passenger miles flown in economy class didn’t exceed that of first class until 1961, according to commercial aviation news site Simple Flying.

“It was a rare day when the airplane was full,” van der Linden recalls wistfully of flying in the 1970s before deregulation. “You always had leg room, even in six-across seating. Usually in a row of three, at most there’d be two people, so you could spread out and go to sleep if you wanted to.”

While 65 percent capacity was great for passengers, it wasn’t so for the airlines. Before long, the lounges, beds, and other amenities expected in first class started disappearing as airlines focused on fitting more seats in both cabins. Meanwhile, lower-cost carriers like Texas-based Southwest Airlines emerged on the scene, competing regionally with lower fares that forced other carriers to drop their prices. Amid the so-called “$13 Fare War” with bitter rival Braniff International Airways in 1973, Southwest briefly became the largest distributor in Texas of premium liquors including Chivas and Smirnoff, when it offered a promotion of a full-fare ticket for $26 that included a free bottle of premium alcohol.

But the expansion of economy hadn’t even really begun.

All Bets Are Off

Starting with the Nixon Administration in the late 1960s, both sides of the political aisle began advocating for regulatory reforms that decreased federal involvement in America’s largest industries — from energy to rail to airlines — to stimulate economic growth. This culminated in 1978, when Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act, which undid all federal aeronautics controls that had been in place since 1938. This meant carriers were finally free to set their own prices and openly compete for routes and airports. What was supposed to inspire a “flowering of creativity,” as Foss calls it, instead became a race to the bottom.

Amid ruthless competition to cut ticket prices, airlines suddenly needed to fill every seat in order to remain profitable. Plane maps were reconfigured to cram more people into coach, and airlines carved out a new business class from the upper end of the economy cabin.

“Airlines don’t make money off of coach; they make their money in first and business class,” van der Linden says. “But without coach back there, they can’t break even.”

Perhaps the most consequential move post-deregulation was the emergence of frequent-flyer programs, which “rewarded” customers for staying loyal. The premise is if you spend your money with one airline, it will give you miles or points to redeem for free flights, better seats, and other upgrades. In effect, these programs exploit the perception of savings and longing for status to make users want to earn, which in turn requires them to spend.

“Suddenly, people have loyalty to airlines they never had before,” Foss says. “Prior to frequent flyer miles, if you needed to go to Cleveland, you checked what airline flies to Cleveland nonstop. Now the question becomes, ‘How do I get to Cleveland with the airline I want to fly to get a vacation for free? If it takes two stops, I’ll take two stops.’”

Amenities no longer had the same pull; moreover, following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, airlines largely stopped in-house meal service in economy and contracted out snacks and drinks. The new landscape led to a rash of consolidations and bankruptcy filings.

Wisconsin-based Midwest Express, beloved for its ample legroom, leather seats, and gourmet meals that included warm chocolate chip cookies (baked in-flight!), was bought out by Frontier Airlines in 2010. Foss likewise recalls an earlier casualty, Texas-based Muse Air, whose excellent in-flight food was no longer enough to tempt consumers with its premium ticket prices by the late ‘80s, when it sold to another carrier.

“The thing that killed them both was frequent flyer miles,” Foss says. “People will almost always go for the deal.”

As points have matured into their own form of currency, intermediary sites like The Points Guy have swelled into profitable businesses simply through helping consumers navigate the complicated web of airline deal-chasing. Since its launch in 2010, The Points Guy has written tens of thousands of blog posts covering everything from points-maximizing travel routes to rewards programs’ fine print. The site will even sign you up for premium co-branded credit cards like Citi and AAdvantage, which allow you to spend your way to elite status without even stepping foot inside an airplane. (This, by the way, is how the site makes money, per The New York Times.)

For airlines facing ever-tighter competition and seesawing oil prices, selling rewards has become more reliable and profitable than flying people from place to place. Banks win by recruiting new customers. Consumers win, too, with free trips and luxurious upgrades.

Which brings us back to the sad state of affairs in economy — a not-so-subtle hint that our only way out is to play the rewards game, or as Foss puts it, “The more prison-like you make economy, the more likely business travelers who are not cost-conscious will demand to be in the front cabin.”

Meanwhile, the rest of us have credit cards to open and strategic, convoluted travel to plan.

Then again, as all points programs start to look alike, it would make sense to once again care about the swill in our plastic cups, right? Delta Air Lines would argue that they are, in fact, competing in economy-cabin amenities, via recently upgraded offerings aimed squarely at Gen Z and millennial travelers, like Topo Chico Hard Seltzer and Miss Vickie’s kettle chips, women-owned Une Femme Wines, farmer-direct tea company Thrive Farms, and Black-owned Du Nord Spirits. The company is actively seeking to double its spend with Black- and minority-owned businesses and doing the legwork to make it happen.

“Delta worked alongside Du Nord for over a year and a half to ramp up their capabilities to provide us with the products we need for our volume of customers,” a Delta spokeswoman says. “It was a truly special moment when their 50-milliliter bottles were put in production for the first time. It was emotional.”

Would a decent cocktail or all-I-can-drink-Dom poured on another airline with its own confusing path to free trips and luxurious upgrades be enough to lure me away from my current, albeit elusive, path to the lowest premium tier on American? The five open tabs on my browser, including a piece called “14 Ways to Earn Loyalty Points on American” by The Points Guy, would suggest otherwise.