In case you haven’t heard, tequila is having a serious moment in the U.S. According to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS), the nation’s tequila volume has grown by 180 percent since 2002, increasing by an average of 6.2 percent year-over-year. The spirit’s explosive stateside growth has given mezcal a boost, and fellow agave-based spirits like raicilla and bacanora are getting more attention, too.

Despite this rise, many agave drinkers don’t actually know what makes each spirit different. (Just think of the last time you heard mezcal described as “tequila, but smoky.”) Similar to protected wine regions like Bordeaux or Prosecco — which have guidelines from their respective governments outlining how each wine must be produced — many agave-based liquors are also protected with Denominacion de Origen (DO) status from the Mexican state. These DO safeguards restrict not only which regions these spirits can be produced in, but how they must be produced and which agaves they can be produced from.

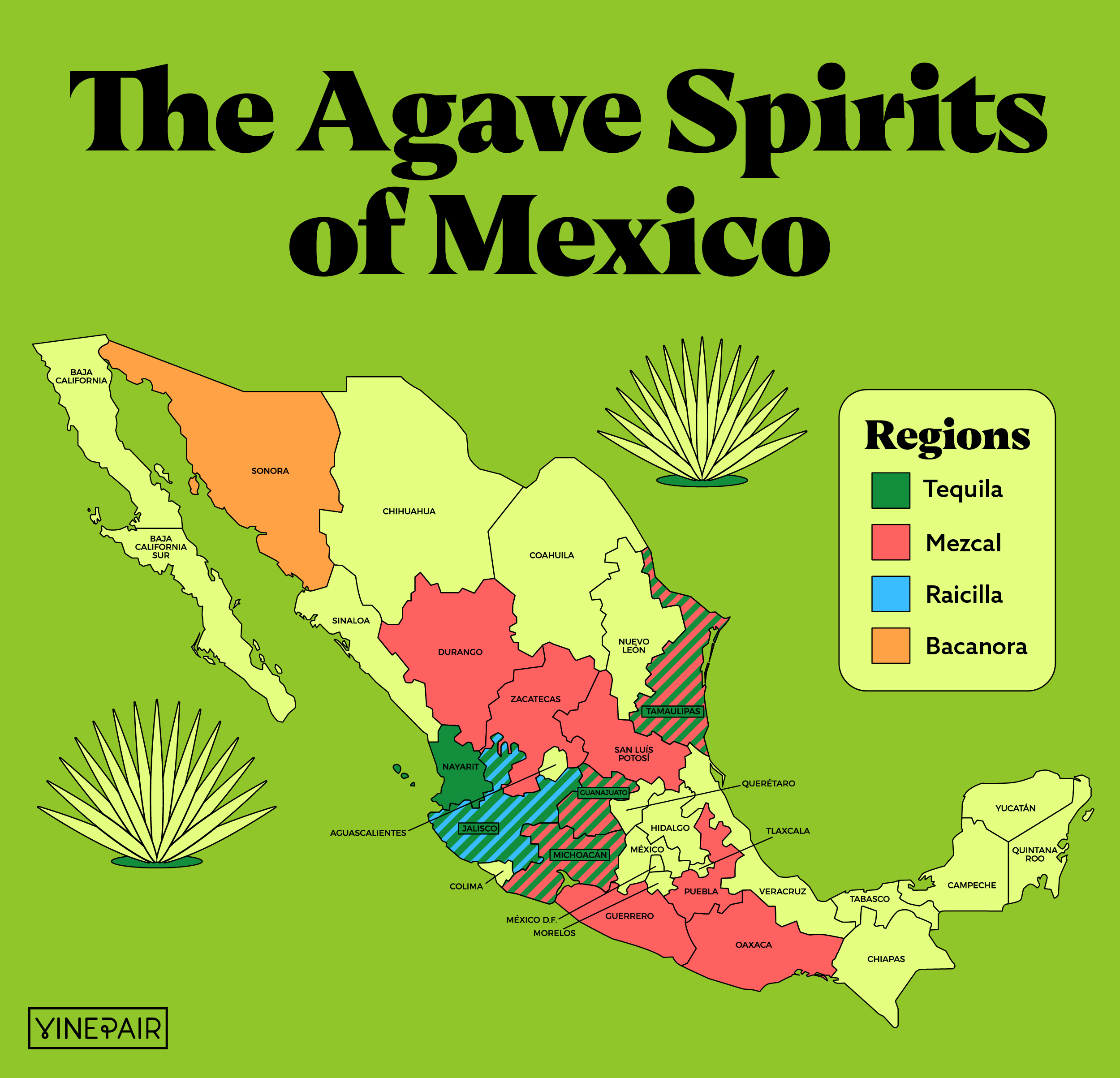

Tequila, for example, must be made from Blue Weber agave in the state of Jalisco or parts of Guanajuato, Michoacán, Nayarit, and Tamaulipas. While drinkers may encounter other agave spirits from other regions that taste strikingly similar to tequila, they still can’t legally be called tequila. The same premise holds true for less ubiquitous agave spirits.

Here, we take a look at the most popular agave spirits from Mexico and share our visual guide of where they’re made.

Tequila

For a spirit to be labeled “tequila,” it must come from one of five Mexican states: Jalisco, or specific municipalities in Guanajuato, Michoacán, Nayarit, or Tamaulipas. Beyond regional restrictions, the Mexican government — which awarded tequila with its DO status in 1974 — requires the spirit to be distilled from 100 percent Blue Weber agave, and it must be proofed between 35 and 55 percent ABV. If the spirit does not meet these exact specifications, it must be labeled as mezcal or the more general “agave spirit” depending on its origin.

In terms of production, all tequila is produced by cooking agaves’ cores, or piñas, via slow-roasting and steaming in above-ground ovens. The resulting juice is then fermented with yeast, distilled, and aged, depending on what type of tequila its distillers are aiming to produce. Throughout the maturation process, aged tequilas like reposado and añejo will commonly take on flavors like vanilla, honey, or baking spices while still allowing the spirit’s signature herbaceousness and vegetal notes to shine.

Mezcal

Mezcal is also protected by DO status. According to the Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM), the organization that certifies the spirit, mezcal must be distilled in the states of Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Puebla, Michoacan, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. From there, restrictions loosen slightly: Unlike tequila, which can only be made from one type of agave, mezcal can legally be distilled from over 30 varieties of the plant, the most common including Espadín, Tobalá, Tobaziche, Tepeztate, and Cenizo. Once the agaves are harvested, the vast majority of mezcal is produced by cooking the plants in underground pits before fermentation and distillation, which provide the spirit with its signature smoke-soaked profile.

Raicilla

One of the most recent agave-based spirits to be granted protected status is raicilla, which received its DO in 2019. Made exclusively in 16 Jalisco municipalities and one in Nayarit, the spirit is a regional type of mezcal produced in one of two styles: de la Sierra (from the mountains) and de la costa (from the coast). Producers may opt to use a variety of agave strains in raicilla production, with Agave maximiliana the most common in mountainous expressions and Agave angustifolia the most popular among their coastal counterparts. Given the spirit’s relatively new protection, there is no regulatory body overseeing and certifying production yet, though methods for how the spirit is to be distilled were outlined in the DO declaration.

The statement allows for the cooking of agaves in autoclaves and extraction via roller mills and permits fermentation and distillation in stainless steel, methods similar to those used in industrially made mezcal. However, many raicilla producers opt for more artisanal or ancestral distillation practices, cooking agaves in pits or above-ground ovens and distilling in more specific vessels. Less smoky than mezcal, raicilla often delivers floral, fruity, or mineral flavors that are highly dependent on terroir. Raicillas hailing from the coast will lean on the drier side, while those from the mountains may taste slightly sweeter.

Bacanora

Although bacanora has been distilled in Mexico for over 300 years, making the stuff was actually illegal until 1992. Just eight years after production was made legal, the spirit was granted DO status, which restricted production to eastern Sonora. Guidelines for the spirit are vague, though according to law, it must be distilled from only Agave angustifolia (more commonly known as Agave pacifica). While some distillers roast their agave piñas in underground pits, others steam-cook the plants before crushing, fermenting, and distilling the resulting liquid. Meeting somewhere between tequila and mezcal flavor-wise, bacanora is often vibrant and washing the palate with vegetal and floral notes along with a hint of smoke.

*Image retrieved from Stephan Hinni on Unsplash