The best parts of being a beer writer are self-evident. And to be honest, there aren’t really any hidden downsides. It’s a pretty soft gig. But if there’s one thing that inches my beer research ever so slightly closer to “job” than “hobby,” it’s the constant pressure to try new things. Of course it’s fun to see what’s out there, and if I didn’t like to stretch my tongue as far as possible I’d have opted for the ditch-digging life that the guidance counselors recommended, but it’s still a bit stressful to make so many of my beer choices based on their potential to lead to a good story rather than simply a good time.

But even though the quest for novelty complicates my beer life, it ultimately enriches it. If I didn’t always need new stuff to talk to you guys about, I probably wouldn’t have tried a coffee-infused, 100-percent brettanomyces IPA last week. It was just as good as it was weird (full report to come), and it served as a useful reminder of how great these days are for American beer drinkers in general and for writers in particular. So I was in high sprits when I headed out to the local Whole Foods last Friday afternoon to see what surprises the beer aisle might hold.

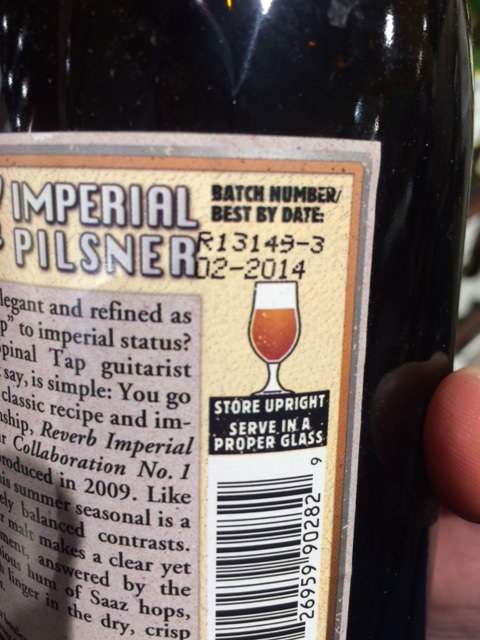

There was a ton of good stuff, as usual, and at some of the best prices in town. My eye was drawn in particular to a bottle of Boulevard Reverb, an imperial pilsner from the Kansas City brewery’s acclaimed Smokestack series. I love Boulevard and I love pilsner, and the imperialization of a normally humble style makes for good article fodder, so I was ready to happily drop $10 on the 750-milliliter bottle until I spun it around and saw this ghastly sight:

Alas, in addition to there being a ton of good stuff out there, there’s also a ton of used-to-be great beer languishing on shelves waiting for some poor sucker to come along and give it a better home than it deserves, i.e., his unsuspecting gut rather than down the drain.

America’s 4,200 breweries produce at least 10 times that many different beers each year, and while not all of them hit retail distribution, more than enough do to fill our oversubscribed beer aisles with way too many once-promising bottles that are long past their prime. And buying local is no guarantee of freshness. It’s hard for newer and smaller operations to predict demand, and local distributors and retailers are eager to give their neighbors a shot, which can lead to shelves full of IPAs with low carbon footprints but high dust accumulations.

The typical craft beer aficionado despises Anheuser-Busch InBev as much as she adores her Russian River Brewing hoodie and her golden retrievers, Simcoe and Sierra, and while I tend to agree from a flavor perspective, I still hold one huge soft spot for the world’s largest beer conglomerate. Budweiser should be forever applauded for their decision to introduce “born-on dates” to their retail packaging in the mid-90s. Nearly every beer produced gets demonstrably worse as it ages, and while Samuel Adams gets credit for freshness dating their beer as far back as the mid-80s, it wasn’t until AB followed suit that freshness became a front-and-center issue that even casual drinkers began to notice.

Stone’s Enjoy By Series of double IPAs has taken freshness transparency to another level, with each beer named after its expiration date, which is 35 days after it’s bottled. This is fantastic in the obvious ways and also because it leads to comical farces such as the beer store closest to my house still trying to get $9 for a beer called Enjoy By 12/25/15 on 1/13/16 (and counting). But when the best-by date is hidden on the back of the label in small print, old beer is no joke.

The price [of beer] is rising as fast as the quality. And that’s perfectly fair, as long as all three tiers of the distribution system—brewery, wholesaler, and retailer—are dedicated to providing consumers with fresh beer.

Boulevard is to be commended, though. I was able to dodge the Reverb grenade because the brewery respects its customers enough to print the best-by date clearly, in dark ink on the white label. Other breweries, such as Lagunitas, make it a bit harder, printing a Julian date code (in which the “267” equals September 24th, the 267th day of the year, for instance) in dark ink on the neck of a brown bottle. Still others, such as Rogue, don’t even give the consumer the opportunity to hunt down and decipher a date puzzle. (Freshbeeronly.com is an excellent resource for figuring out which breweries use which codes.)

There’s some disagreement over who bears the responsibility for old beer. Breweries are legally mandated to contract third-party distributors to sell their beer to retail stores and bars. Once this Reverb left its Missouri birthplace sometime in late 2013, Boulevard had very little influence over where it ended up—or when it got there. Peter McCann, Wine and Beer Buyer at Whole Foods Market of Greater Boston, could only tell me that it was “unusual to find something that far out of code” and that he “had no idea how it happened.” He was apologetic and concerned, and I have no doubt he’ll rectify the situation. But no one’s explained to me how it happened in the first place, or how it’ll be prevented from happening again. Calls to Burke Distributing, which handles Boulevard sales in metro Boston, were unreturned.

One thing is certain: Freshness matters. I asked Jenny Pfäfflin of beer-education pioneer Cicerone.org just how much it matters, and she told me the following: “Packaged pasteurized beer that’s been taken care of (i.e., refrigerated and kept out of direct light) can keep for up to 6 months, but you may see flavor degradation in as few as 90 days. For IPAs, you may experience a drop-off in hop aroma by the 90-day point; for a beer style like a wee heavy or an import lager, it will probably be fine at 6 months.”

With all due to respect to Pfäfflin, who knows more about beer than I know about spelling my own name, I’d say that those guidelines are, if anything, on the patient side. One of Portland, Maine’s, new hoppy ale darlings told me last year that his beers are best between their 4th and 6th days out of the tank. Now, that guy’s clearly nuts, and I wish I could remember what he claimed undermined the first three days—a temperature issue, perhaps?—but he makes great beer, and I agree that it’s better within the first month.

Use extreme caution when dealing with breweries that refuse to provide any hint as to when their beer was born.

This all varies from beer to beer, of course, and from drinker to drinker. To get a feel for how a conscientious brewery handled best-by parameters, I asked Boulevard Ambassador Brewer Jeremy Danner to walk me through how their process works:

“Boulevard has employed some form of code dating for 15-plus years. In the earlier days, it was as simple as using a bandsaw to cut a notch on a label to indicate the best-by month and has evolved to printing two dates on each bottle as well as any exterior box or carton. The first date indicates the date and time the beer was packaged as well as the bright tank from which the beer came. The second date printed on the label is a best-by date. Our best-by dates are based on real-time results from our tasting panel, which tastes bottles from our library as they age. We use the best-by date to indicate when we feel the beer is no longer an excellent example of our intentions. Our more delicate or hop forward beers have the shortest shelf lives, while higher alcohol or barrel-aged beers receive best-by dates that are up to two years out from the packaging date.”

Light, oxygen, heat, and time are fresh beer’s most troublesome opponents. Improved packaging has helped eliminate a lot of the light-shock problems that plagued the clear-glass-bottle era, and oxygenation tends not to be much of an issue for canned and bottled beer unless something goes drastically wrong. But few stores have the cooler space to keep all beer as cold as it ought to be, which accelerates the expiration date ahead of whatever might be printed on the label.

Beer’s getting better all the time, but the price is rising as fast as the quality. And that’s perfectly fair, as long as all three tiers of the distribution system—brewery, wholesaler, and retailer—are dedicated to providing consumers with fresh beer. That’s not always the case, and even when it is, logistics sometimes undermine good intentions.

That means it’s up to we humble drinkers to be vigilant about checking for freshness before we buy beer from a retailer. If a beer’s out of date, tell someone: the store, the brewery, social media. And use extreme caution when dealing with breweries that refuse to provide any hint as to when their beer was born. I don’t need to see my president’s birth certificate, but when it comes to something as important as beer, I need proof.