Any industry that marries the existence of experts, the spending of cash, and the words “acquired taste” as exquisitely as the wine industry does is bound to intimidate the uninitiated. But how far will people go to sell anxious to impress consumers of wine its paraphernalia? Pretty far, it turns out.

Riedel glassware has made a killing selling the claim, now widely embraced by wine establishment, that the shape of a glass can improve the taste of the wine deposited therein. “Perfectly designed glassware enhances the aroma and the flavor of all aromatic beverages,” claims the brochure of Riedel, a $350 million glassware company that sells gorgeous and pricey “grape varietal specific” glasses and decanters (varietal specific means specific glasses for different wines like Merlot, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet, etc.). “Riedel has researched the grape varietal sensation, leading to the conclusion, on which the world’s wine experts agree; that the enjoyment of aroma, taste, texture and finish of a wine, is maximized by using the right ‘WINE TOOL’,” boasts the brochure. Also included are supporting quotes from the likes of leading U.S. wine critic Robert M. Parker Jr: “The effect that their glasses have on fine wine is profound. I cannot emphasize enough what a difference they make;” and also French critic Michael Bettane: “RIEDEL makes it possible to fully appreciate all the nuances of aromas and tastes from the best wines of the world.”

The brochure goes on to suggest helpful ways to maximize your wine experience, such as this helpful hint about financing your glassware: “Plan to invest in ONE glass as much as you spend on average for a bottle of wine,” and this helpful hint about why you need to buy so many Riedel glasses: “One glass is not ideal for all styles of wines… A wine will display completely different characteristics when served in different glasses,” and this pseudo-scientific hint which should further convince you to buy even more glasses: “Grape varietals carry in their DNA unmistakable flavor profiles, which add to the importance of selecting the appropriate glass.”

But is it true? Do different wines really need different glasses? Does the shape of a glass actually affect taste? Or is this a new kind of snake oil being sold to the aspirational set eager to convince others of their olfactory prowess?

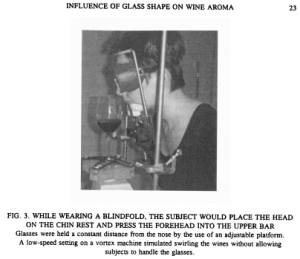

In 2000, two scientists set out to test the hypothesis and the proceeds were published in 2002 in the Journal of Sensory Studies. Jeannine Delwiche and Marcia Pelchat of the Monell Chemical Senses Center gave subjects four glasses to smell and drink from with the same wine in them: a square-shaped crystal water goblet, a standard, cheap restaurant wine glass, a Riedel Chardonnay glass, and a Riedel Bordeaux glass.  They created a nifty blindfold out of goggles, to prevent the aesthetics of each glass from interfering in the way the subjects judged the smell and taste of the wine, and they also created a chin-rest, to control for distance from the glass.

They created a nifty blindfold out of goggles, to prevent the aesthetics of each glass from interfering in the way the subjects judged the smell and taste of the wine, and they also created a chin-rest, to control for distance from the glass.

Their conclusion was not good news for Riedel. “For the intensity ratings of most attributes, no significant difference was found between the glasses,” they write. (There was, bizarrely, a difference between the way men and women rated the “mustiness” of the wines; women rated it higher than the men.) Otherwise, “The only significant finding was that likers of red wine gave higher liking ratings than did dislikers of red wine, which is as one would expect.” There was a small difference in intensity that the subjects registered—the aroma of the wine from the Bordeaux glass registered as “less intense,” probably because it is taller, and the wine further from the nose. But overall, they concluded, “None of the correlations are significant.”

It seems that the effects of the Riedel glassware are psychological more than scientific. As Pelchat put it when reached by phone, “A table set with seven different Riedel glasses just looks beautiful. I appreciate it as a work of art. Do you really need to have them? Maybe not.”

Pelchat says she and Delwiche paid for the study themselves. “Mr. Riedel visited and we asked if he wanted to fund the research and he said, ‘Yes, as long as you don’t find anything negative about the glass,’” she recalled. “As a scientist, I couldn’t take on that kind of research.” (Riedel did not respond to requests for comment about this statement, though another scientist present at the interaction between Pelchat and Riedel confirmed the comment was made.)

But the research seems to have made little dent in the way experts in the wine industry write about Riedel and the importance of different wine glasses. New York Times writer Eric Pfanner wrote in 2012, “While I have also seen research that questions the validity of this thesis, Riedel glasses do seem to make wine taste better.”

Another study may help explain this curious phenomenon. It turns out, the psychological effects of wine tasting extend even beyond the shape of the glass. In 1998, Frédéric Brochet, a neurophysiology researcher at University of Bordeaux, gave subjects of a study two glasses of wine to choose from, telling them that one was very expensive and one very cheap, when in fact, they were the same wine. The subjects overwhelmingly described the “expensive” wine as good, and the “cheap” wine as bad.

“Expectations have an enormous impact,” Brochet told Gourmet’s Daniel Zwerdling in 2004. “People can, in fact, tell the difference between wines. But their expectations—based on the label, or whether you tell them it’s expensive, or good, or based on what kind of wine you tell them it is, the color—all these factors can be much more powerful in determining how you taste a wine than the actual physical qualities of the wine itself.”

Zwerdling concluded that “Riedel and other high-end glasses can make wine taste better. Because they’re pretty. Because they’re delicate. Because they’re expensive. Because you expect them to make the wine taste better.”

How much money you want to pay for that placebo, and how many different glass options you want to have, is up to you.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer. She lives in Brooklyn.

Header image via Shutterstock.com