Warehouse X doesn’t sound like somewhere you wanna be. Whether you’re talking superhero universe or regular non-spandexed human life, warehouses are generally reserved for angry foreman hauntings and terrible, glow-stick thrusting raves. Another alternative: they never quite named the place, but we’re pretty sure Warehouse X is where they took Mel Gibson’s character in Conspiracy Theory. (Captain Picard was never more terrifying.)

The only place in the world where anything good has, or will, ever come out of a “Warehouse X” is Kentucky. And that’s because said warehouse belongs to distilling behemoth Buffalo Trace. We knew they were successful; bold enough to make a partnership to revive the saintly ghost of Pappy Van Winkle. But we didn’t know they were also a bunch of adorably lab-coated whiskey geeks, brave enough to, well, mess with a good thing.

Though we should all be thankful that they are, since Warehouse X—just a letter designation in Buffalo Trace’s alphabet soup of buildings—is where expert distillers get together to tinker with the finicky, nuanced elements of bourbon production.

Buffalo Trace has never been shy of innovation—they’ve mucked around with everything from mash bill components to char levels and beyond. But Warehouse X serves an entirely different, specific purpose: testing the impacts of the environment, complete with four distinct “chambers,” on the maturation of bourbon. The major goal is nothing less than to find the “Holy Grail” of bourbons because, according to the company, “so far the perfect bourbon has yet to be made.” (Pappy fans, chill, this might benefit you, too.)

There’s a certain similarity between the philosophy at Warehouse X and the meticulous, hyper-specific perfectionism that drives the evolution of Japanese whisky. Whereas Scotch and Irish whisk(e)y abide by certain unalterable traditions—and after a certain point absolutely do not interrupt or “tweak” the process—Japanese whisky isn’t bound by embedded tradition, obsessing over a Darwinian whisky ideal rather than a trusted or beloved archetype.

Buffalo Trace is doing something kind of exactly in between—respecting the fundamentals (if you’re just a bourbon maverick, you’re irrelevant, or irreverent, possibly both) while making space for innovation. And that eventual step to establish Warehouse X was partly the result of a tornado. BT folks had been mulling establishing an experimental bourbon playground for a while, but, like most progress, it would’ve been a bit expensive. It wasn’t until a tornado tore the roof off of Warehouse C (less terrifying sounding, right?) and the surviving bourbon aged, very successfully, for 6 roofless months that the crew re-invested in some serious environmental experimentations.

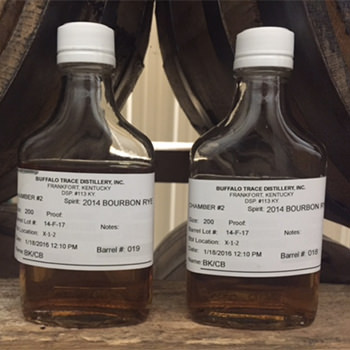

Hence Warehouse X and its four “independently operating chambers,” plus open-air patio and Microstill. The building (the first that Buffalo Trace has built new in about 60 years) has intentional and carefully monitored variations in “natural light/UV,” “temperature,” “humidity,” and “airflow.” (Sorry, the quotes must must seem like we don’t actually believe in stuff like temperature. We do. We really do.)

Said X-periments (again, sorry) will take place over 20 years, segmented, with successful 2-year experiments getting longer follow-ups. And those time periods are fairly essential, given the long-term influence of climate. Remember, Bourbon can be made anywhere in the country, but there are many who reasonably claim the climatic influence of Kentucky is essential to the proper maturation of a fine, succulent, porch-sippin,’ pontificatin’ bourbon. Which is to say, manipulating the basic atmospheric influences within classic bourbon country could yield something really damn tasty—like that accidental Warehouse C tornado whiskey—or, eventually, the perfect Holy Grail bourbon?

Which, yeah, none of us will be able to buy. Not least because Buffalo Trace isn’t actually looking to sell out via climate kitsch (like “Hey! This is bourbon that got hailed on! Pay extra?”) What they’re absolutely willing to do, however, is share the progress of current experiments (this one is slated to be done in June) with their audience. The idea really is to examine if and how (and to what degree) the basic elements of a yearly climate impact the character, and greatness (which is not to say the perfection, necessarily) of a bourbon. Which should, in theory, help Buffalo Trace—and bourbon experimenters the whiskey world over—better influence outcomes in the game of risk that is wood-aged corn whiskey.