Beer production in East Asia may actually be older than we thought.

According to a new study published in “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” archaeologists have uncovered evidence of rice beer dating back approximately 10,000 years at the Shangshan site in China’s Zhejiang Province.

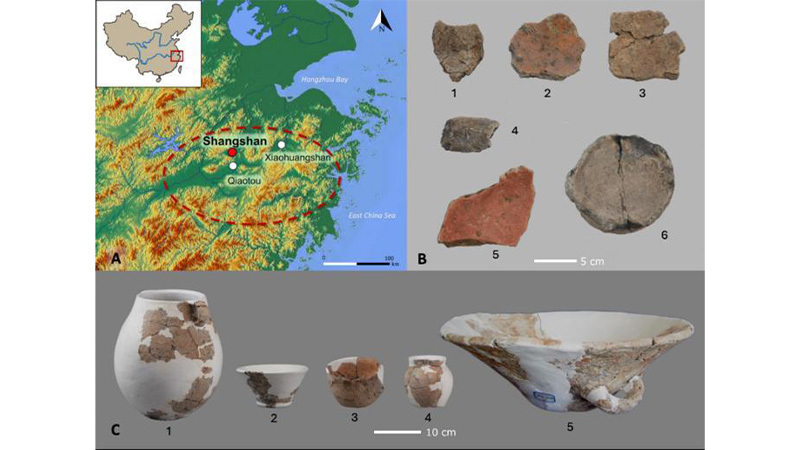

The study — carried out by researchers from Stanford University, the Institute of Geology and Geophysics (IGG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (ICRA) — was designed to better understand the origins of rice domestication and alcoholic fermentation in China. To do so, the researchers analyzed microfossil remains on pottery vessels that would have been used for fermentation, serving, storage, or cooking.

According to Stanford University professor and first author Li Liu, researchers focused on identifying phytoliths, starch granules, and fungi to provide insight into how the pottery was used for food processing methods at the site. This analysis revealed traces of domesticated rice phytoliths in the pottery clay residues.

“This evidence indicates that rice was a staple plant resource for the Shangshan people,” revealed co-author Jianping Zhang of IGG in a statement.

In addition to establishing the central role of rice, the researchers also discovered several elements characteristic of fermentation processes including starch granules displaying enzymatic degradation, fungi associated with brewing methods, and yeast cells. In analyzing the distribution of the fungus and yeast remains, the scientists found that there were higher concentrations in the globular jars, suggesting that particular vessels were linked to specific functions, such as alcoholic fermentation.

This newly discovered evidence of rice beer represents the earliest known occurrence of alcohol fermentation in East Asia, shedding new insights into the origins of rice domestication and beverage production.

“These alcoholic beverages likely played a pivotal role in ceremonial feasting, highlighting their ritual importance as a potential driving force behind the intensified utilization and widespread cultivation of rice in Neolithic China,” said Liu.