It’s one of the most divisive areas in winemaking. Fermentation, by either wild or industrial yeasts, has become synonymous with the battle between all that is natural, and the convenience and consistency of man-made machination. If natural wine risks becoming a runaway train, then wild fermentation is a flag you wave as it passes by.

For some, the thought of using “industrial” yeast cultures to ferment wine is the ultimate in faking it. They claim that adding these yeasts, deliberately bred to impart desired flavors to the wine, is a betrayal of the concept of terroir — the concept that wines should taste of the place the grapes are grown.

Others claim that the risks involved in allowing “natural” yeasts to carry out the ferment are unacceptable, and can lead to faulty or weird wines. They scorn the idea that native yeasts are part of terroir, arguing that most wild ferments are carried out by commercial strains resident in the winery, after, that is, the wild spoilage yeasts present on the grapes have had a few days to cause havoc in the ferments.

Who is right?

*

We sometimes forget that, like cheese, wine is a microbiological product. The grapes get all the glory, but that isn’t very fair.

Wine is a product of fermentation, the process by which yeasts turn sugar into alcohol in order to yield energy. Afterward, there’s a second bacterial fermentation, called malolactic fermentation, in most wines. This adjusts their acidity and makes them more stable.

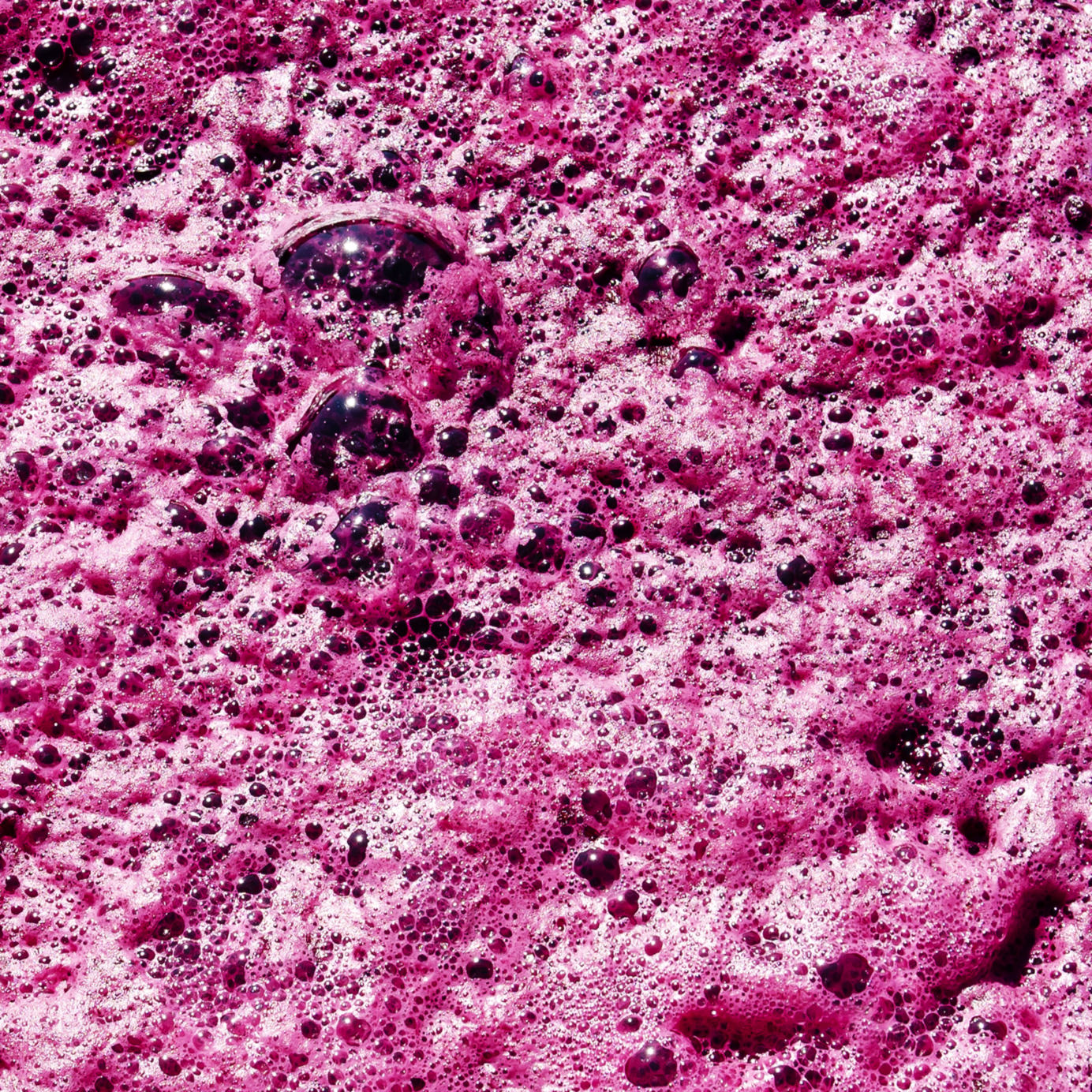

Yeasts are tiny. We can’t see them, and the only evidence of their activity is a steady stream of small bubbles of carbon dioxide rising to the surface of fermenting grape juice. But what they do is astonishing: They transform simple, sweet-tasting grape juice into something much more complex — a liquid that has the potential to be profound, and which, with its alcoholic content, has transformative powers.

Starting when wine was first made, some 8,000 years ago, until Louis Pasteur proved the existence and importance of yeasts, in 1863, the transformation of grape juice into wine was a mysterious process.

Freshly harvested grapes contain pretty much all that is needed to make wine. They have enough sugar for yeasts to make enough alcohol to keep the wine stable, and enough acidity to make it taste fresh and preserve it. Red grapes have tannins in their skins that help make the wine more robust, and, perhaps most importantly of all, harvested bunches also have a natural inoculum of wild yeasts that carry out the necessary fermentation. All humans need to do is crush the grapes and get things going.

For much of wine’s history, nothing was added, save for a bit of the preservative sulfur dioxide (created by burning a sulfur wick in the fermentation or storage vessel, usually a barrel). Fermentations were carried out using whatever yeast happened to be in the grapes.

That was until the 1960s. In the middle of the last century, dried, cultured yeast strains started being sold in packets. This is when the yeast story starts getting a bit controversial.

Active dried yeasts, a midcentury modernization of 19th-century pure starter cultures, took off soon thereafter, especially among New World winemakers. They took a lot of the risk out of fermentation and, in the New World, where wine production was accelerating, the demand was for clean, attractive fruity wines. Commercial yeasts promised winemakers a much clearer route to this goal than relying on grapes alone.

If you read a current yeast producer’s catalogue, you’ll be amazed by the variety of yeasts on offer, and the flavor promises they make. You want a floral, fruity red wine with exotic cherry fruit? This strain of yeast can steer the wine that way. Want an exotic Sauvignon Blanc with a big elderflower and passionfruit nose? There’s a strain for that too.

Another thing these yeasts offer is security. Want to avoid a stuck ferment with a potentially high-alcohol wine? Or a yeast that will carry out fermentation successfully at very low temperatures (preferred by winemakers who want excessively crisp, fruity whites)? Or a strain that produces low levels of sulfides, or volatile acidity? These all exist.

*

But everything is cyclical. Starting in the early 1990s, wild or indigenous ferments were rare enough that some New World wine producers used them as a marketing strategy. They labeled their ranges “wild ferment,” explaining that this was a particularly funky, living-on-the-edge way of making wine. In a large cellar, the bravest would risk a rare few barrels to the potential peril of wild ferments.

Now, in the New World, more and more producers are having the confidence to see what their native yeast populations can do. Even this is controversial.

What happens during a wild ferment? Yeasts are present on the grapes when they come into the winery, but most of these yeasts are what are known as non-Saccharomyces, or wild yeasts.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, on the other hand, is the main alcoholic yeast used to complete fermentation in wine. (It’s also the yeast used by bakers.) Saccharomyces cerevisiae does naturally occur in the vineyard, but it can be hard to find on grapes — to the point that, until recently, some people thought this yeast was man-made. Their theory: that it had evolved in conjunction with human activities of baking and brewing, just as modern grains have been selected for so strongly in agriculture that they have little resemblance to the ancestral wild grasses they came from. But with modern molecular techniques, it’s possible to show that they exist in the vineyard environment.

For the first few days of fermentation it’s the more dominant wild non-Saccharomyces species that dominates. This is the heart of the wild ferment: The yeasts produce interesting flavor compounds and textures, and begin the work of turning sugar into alcohol. But they aren’t able to tolerate high levels of alcohol, and by the time the levels creep up to around 4 percent, most of them die, leaving the way clear for the small populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to start doing their stuff. They take over and finish off.

Of course, because this process is natural, it’s possible for rogue yeasts and bacteria to produce off-flavors. This risk can be mitigated by adding a bit of sulfur dioxide, the almost universally used wine preservative, to the grapes on reception, or by making sure that the grapes that make it into the vat are in really good condition.

The advantages of wild ferments are that the resulting wines often have a more interesting texture and more complex flavors. This makes them especially appealing to winemakers.

Moreover, there is an argument to be made that yeast species are part of a wine’s terroir. Recent work using DNA fingerprinting has proven that alcoholic fermentation during winemaking is usually carried out by Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are present in the vineyard and unique to each locale. The yeasts are local to the vineyard area and can help transmit a sense of place to the wine in a strict, literal sense.

*

But before we get too carried away with wild ferments, let’s take a more nuanced view of yeasts. While yeast companies’ catalogues claim their products can change the flavor of the wine, it’s worth remembering that most yeasts are selected from nature: They are isolated from ferments with desirable outcomes, and then cultured and freeze-dried, much as a farmer might save seed from one year to sow the next season.

In some cases, winemakers choose to use cultured yeasts because they have a neutral impact on the wine and they allow for consistent results. One winegrower I spoke to in the Loire worked very naturally and wanted his wines to reflect his distinctive terroirs. He found that wild ferments resulted in wines that were quite different each year and which didn’t show off the site differences that he was so keen on his wines expressing, so he inoculates.

The wine world is rarely completely black and white, and the topic of wild versus cultured yeasts illustrates this well. Yeasts, cultured and natural, are part of the winemaking toolkit, and it’s up to every winemaker to decide what fits his or her intentions best.

I’m glad that wild fermentations are more common these days, and that there is a link between the organisms that carry out these fermentations and the vineyard. But I’m also grateful for the sophisticated microbiological work carried out by yeast researchers, resulting in interesting products, such as speciality yeast strains and even cultured non-Saccharomyces yeasts for those who want wild ferment character without the risk. Both are necessary, and in the right hands can help make more interesting wines. In this sort of fight, we all win.