The cork-or-cap debate certainly isn’t settled, and we’re glad to contribute to the ongoing research by opening as many bottles as it takes until somebody decides for good, or we’re all too drunk to care just what was keeping the bottle closed in the first place.

But for those of us who’ve been reading or listening in, it kind of feels like the cork or screwcap debate has been going on for ages—maybe because it’s hard to stir up a lot of passion when you’re talking bottle closures. For a sommelier, sure, there’s definite professional interest; uncorking the bottle is part of the traditional theater of wine service. Make it a screwcap and the somm might as well be opening a bottle of Diet Coke. And for wine professionals, especially winemakers, there are concerns over everything from simple tradition to oxygen transfer to economic efficiencies and cork taint. It’s a real, if slightly unsexy, debate. It’s also pretty recent.

Not that screwcap technology is historically recent. In fact screwcaps of all variety have been around for over a century and a half, well before they were keeping our bottles of perfectly chilled New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc nice and grassy green. John Landis Mason actually revolutionized food preservation technology with his eponymous and now hipster-beloved jar, patented in 1858; the threaded screw-top made a much safer bacterial barrier for canning purposes; previous methods involved a flat tin top and hot wax to seal the sides, and probably a few prayers. About 40 years later, a UK man named Dan Rynalds patented a screwcap for beverages specifically, not for wine but whiskey; it didn’t quite take off. (Rynalds’ screwcap suffered some technical issues with the metal cap directly exposed to corrosive alcohol.)

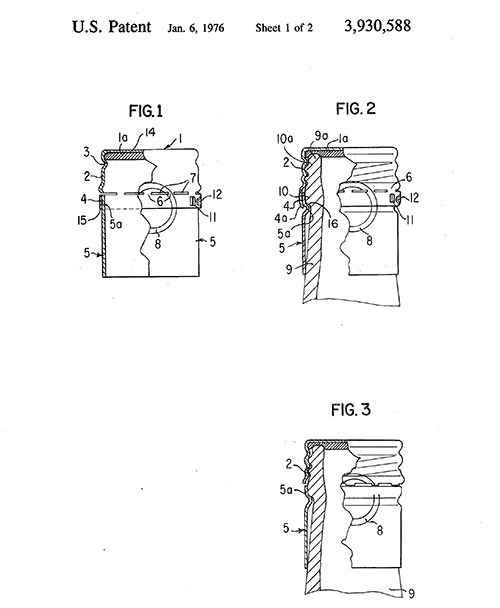

Whatever it encloses (and interesting there’s far less debate where whiskey’s concerned) the “threaded” design of the screwcap has been around for a while (by “threaded” we’re referring to the little lines on the cap itself as well as the top of the bottle, allowing it to “catch” and seal). But the screwcap only came to the wine market a few decades ago, the brainchild of a French company originally called Le Bouchage Mecanique. Translated literally, that means “the mechanical closure,” for which LBM filed a patent in 1976, years after bringing its screwcap to market back in 1959, “grace aux travauax de Jacques Bergeret et Michel Feuillat” (thanks to the work of, well, those dudes).

Considering the stranglehold of tradition on all things French and wine, it might seem surprising that a French company was the first to consider the screwcap as an appropriate wine closure; the truth is, they were commissioned to do so in 1964 by an Australian named Peter Wall, then of Yalumba winery. The cap was patented as “The Stelvin,” a name that isn’t in common usage outside of the professional wine world, likely because it sounds like someone trying to address both Steven and Melvin while also incredibly drunk. It was actually the second incarnation of a screwcap, a longer-necked improvement on the Stelcap, which still included cork in the design.

Fast-forward about 40 years and screwcaps have made some moderate inroads, especially in New Zealand, where they account for nearly 90% of all wine enclosures (compare that with Peter Wall’s home country, where only 15% of the wine output is screwcapped). There’s still resistance, of course. Certain regions in Spain actually mandate the use of cork.

Some of the resistance is economic—an established wine-bottling line would actually have to be retrofitted to change from cork to screwcap closures—while some is more vaguely practical (with historic evidence suggesting cork is beneficial to wine aging). And the rest is just stubborn tradition. We like the way cork looks, and we like the mild excitement of trying to open the damn bottle without breaking the cork. (Especially if we don’t have a corkscrew, which, come to think of it, is at least one more argument for the screwcap.)