Move over, fizzy yellow beer — bright purple has arrived. Ube, a purple yam from the Philippines (pronounced ooh-bae), which has long been prevalent in Filipino sweets, has already taken the food and cocktail worlds by storm. Now, it’s beer’s turn for a mauve makeover, and craft brewers are getting in on the fun with the lightly sweet and brightly colored ingredient.

Generally speaking, craft beer isn’t what we’d call a regular at the dessert table (for the most part). But American breweries like Tilted Mash Brewing in Elk Grove, Calif., are newly taking note of the rise in demand for traditional Filipino flavors and are beginning to integrate them into their brews, preferring ube for its exuberant hue as well as its unique yet mild taste.

“Ube is such a hot item as it is, it’s blowing up in ice cream and Trader Joe’s,” says Tilted Mash sales manager Jay Del Rosario, who points to his Filipino identity as inspiration. “So I said ‘Let’s make a beer.’”

That beer is Ube Bae Cheesecake, an 8 percent ABV imperial sour with graham crackers, cheesecake, vanilla, and, of course, ube. Del Rosario says it was an immediate hit and sold out in a weekend, while the second batch sold out in two days. A third batch that was brewed for an ube festival in Tracy, Calif., in April 2022 sold out in just two hours.

“My phone is still blowing up from that event because people can’t find it,” Del Rosario says, laughing. “I promise, if I made a whole pallet of it again today, that pallet wouldn’t make it through the week.”

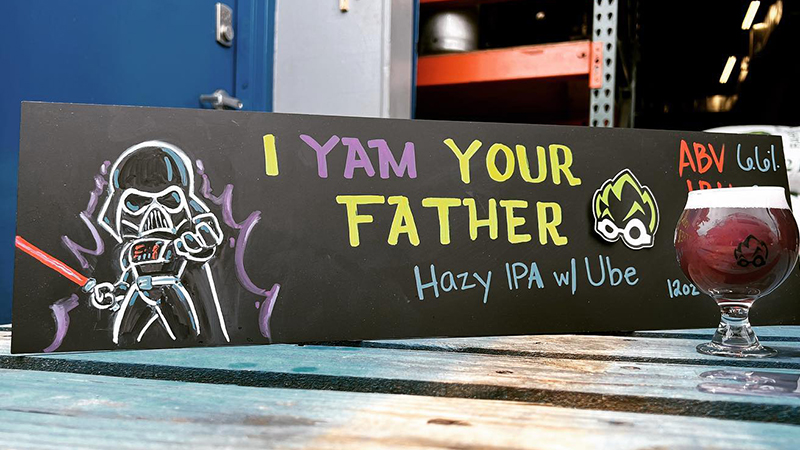

Other breweries like Brewyard Beer Company in Glendale, Calif., are tapping into familial culture to bring the popular flavor into the United States’ craft beer market. Brewyard co-owners Kirk Nishikawa and Sherwin Antonio point to Antonio’s Filipino heritage as an inspiration for using ube in several of their beers, including a 6 percent India pale ale dubbed “Ube Wan,” as well as an 8.2 percent imperial brown lager with coconut called “Ube Macapuno Delight.” Both remain regular releases, despite the fact that ube tends to leave an irritatingly stubborn stain on brewing equipment. “We don’t even really want to put it on tap, because when we do that, it stains everything. It’s pretty crazy,” adds Del Rosario.

But the threat of stains isn’t stopping breweries from figuring out how to use ube for their own eye-catching brews. In San Diego, Harland Brewing Company has even gone so far as to launch an annual “Ube Day” in September to hype its Ube Milkshake IPA, a 7 percent ABV India pale ale with coconut and lactose. “We didn’t know if anyone would care about the beer or even like it,” says Ryan Alvarez, head brewer at Harland. But since its initial release in 2019, demand for the brew exploded. It even inspired another San Diego brewery to try its hand at a one-off ube beer release: Home Brewing Co.

During the pandemic, Home Brewing Co. brewer Cyrus Baluyot decided to brew his own ube beer after tasting Harland’s and being “pleasantly surprised” by the result. His first attempts at home, by his own account, were less than successful.

“I initially boiled down, dehydrated, then blended the ube into a powder and used it during the boil,” Baluyot says. “This was a huge fail, as it made the wort taste like potato.”

He eventually asked Harland’s team how they managed to retain the sweetness and color without the yammy taste, and switched to their method of using ube powder instead of fresh, whole ubes. That tweak turned out to be the ticket. “Once I figured out how much [ube powder] to use, the brewing process was pretty straightforward, treating the ube like a dry hop, adding it towards the end of fermentation,” he explains. Baluyot called his one-time release U.B.E., or Unfamiliar But Enjoyable.

“People familiar with the flavor [of ube] are extremely happy with how it came out. People who aren’t familiar, but are willing to try it out, are shocked by how enjoyable of a beer it is,” he says. Still, he doesn’t plan on regularly brewing it commercially: In true homebrew fashion, it was more of an experiment to see if he could do it.

Despite the obvious commercial success of ube beers, only a handful of breweries — mostly on the West Coast and in Hawaii — have begun to experiment with the flavor. But now that more brewers are getting in on the purple craze, Del Rosario says he hopes it will inspire people unfamiliar with Filipino culture and heritage to continue to learn.

“I wanted to work hand in hand with my culture,” he says, explaining that including family was a crucial part of the process. “My niece is the one who actually designed the label. I involved my family, I involved my culture, and that’s what made it a lot more fun for me.”