Kosher wine has been gaining popularity among mainstream consumers recently, but the laws are detailed, and often complicated. Contrary to popular belief, kosher wine is not blessed by a rabbi; instead, once the grapes are pressed, only Sabbath-observant Jews can touch the wine. If a non-Jew or even a non-Orthodox Jew touches the wine, the entire vat has to be thrown out. In order to make sure that no gentiles or heretics have touched the wine, an inspector (often a rabbi) must have access to the premises at all times, so he can watch for perpetrators.

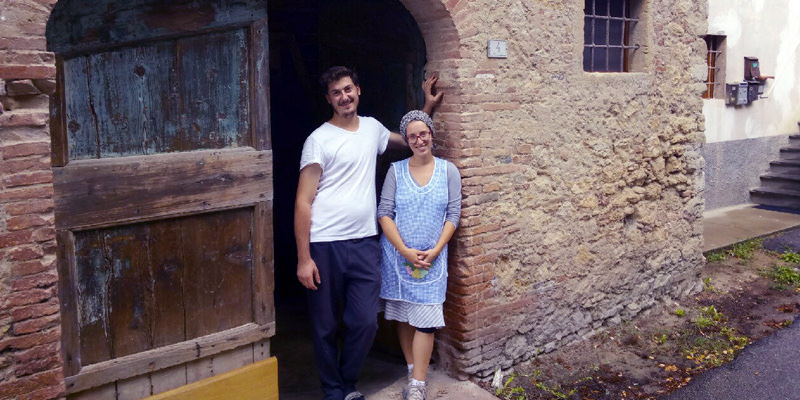

It’s tough – and expensive — enough following all these laws in places like New York or Israel, where rabbis are plentiful and ready at hand. But what happens when you’re the only Jews in a small village on the edge of Tuscany? The owners of a tiny winery recently found out.

Eli Gauthier never meant to become a winemaker. He grew up in Paris in a secular Jewish family and went to England to study Middle Eastern politics. There he met Lara Innesti, a non-Jewish Italian from a wine-making Tuscan family who was studying international relations. They began dating, but their love story was cut off abruptly when Gauthier decided to become more committed to Judaism. He had come to the conclusion that he could never marry someone who wasn’t Jewish, and he broke up with Innesti.

But their love story was not over. Years later, Gauthier was studying in Jerusalem. He went to a party, and out on the balcony, who did he see but Innesti, who was in Jerusalem working for an NGO. Initially, Gauthier says he was angry at her. He thought maybe she had followed him to Jerusalem, reminding him of what they had, just as he was starting to forget her. But Innesti had been on her own spiritual journey. She was converting to Orthodox Judaism.

“I had moved to Jerusalem for a job and some of my friends there were religious,” Innesti told me. “They explained some of the principles of Judaism, and l thought that for once, religion was making a lot of sense in my life.”

Innesti and Gauthier started dating again and eventually got married in an Orthodox ceremony. Gauthier met Innesti’s family, who’d been making wine and olive oil in the Tuscan village of Casciana Alta for hundreds of years.

“I would visit my in-laws on vacation and I would enjoy working in the fields and helping my father-in-law make wine,” Gauthier says. He realized that there was a lack of good kosher wines coming out of Tuscany. “I wanted to make the most of what Lara’s family had there – the contacts and the knowledge and to bring out the quality of Tuscany, under a kosher label.”

Back in university, Gauthier had a worked in a wine shop. Later, he took a job in a non-kosher winery and did a distance-learning degree in viticulture. He now spends the winter months in Strasbourg, studying religious texts at a yeshiva. The rest of the year he spends in Tuscany, making wine.

A half hour from both Pisa and Livorno, the village of Casciana Alta looks as if not much has changed in the past few hundred years. Everyone in the village is distantly related. Cantina Guiliano, Gauthier and Innesti’s tiny winery, originally belonged to Innesti’s grandfather, Guiliano, who used to make wine and olive oil. The winery is named after him, and the label shows him carrying a large jug of wine for a school picnic. The room where the couple makes wine still has the ancient press that Guiliano used to make olive oil.

“We are a small village but centrally located,” Gauthier says. “We tell people to go to Pisa in the morning, then come to us for lunch, then over to Volterra, and then back to Florence, and you’ve had a nice day.”

Cantina Guiliano released its first vintage in 2014 with 12,000 bottles of Chianti, aged in barrels for nine months. It’s smooth and food-friendly, a blend of mostly Sangiovese with some Merlot and Ciliegiolo, a varietal found on the Tuscan coast that brings cherry flavors. In 2015, the winery made 16,000 bottles. This year, they are planning between 20,000 and 22,000. They are also making their first white wine, a Vermentino.

It’s a modest operation, but by design. “I don’t want to make 100,000 bottles,” Gauthier tells me. “I’m happy to make just 25,000 bottles and keep the quality high.”

During busy times, when the grapes are crushed and the wine bottled, Gauthier invites Orthodox Jewish friends from Strasbourg to come and help out, because they are allowed to touch the wine.

And how does he get the rabbinic supervision he needs? Mounted on the wall in the corner of the tiny winery is a video camera. At the other end of the video feed is an Orthodox rabbi, Eliezer Wolff, who lives in Amsterdam. He can check to make sure Gauthier is following the kosher laws.

“He doesn’t tell me how often he checks,” Gauthier tells me. “If there are days or moments that are a bit more risky, I tell him, and he checks more often.”