Bourbon enthusiasts are a rare breed.

It takes a special degree of devotion to comb through Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) filings to get a sneak peek at what new products are in the pipelines. Or to wake up before dawn, camp out at a liquor store and maybe, just maybe, be lucky enough to be one of the few to spend hundreds of dollars on a limited-edition, allocated bottle.

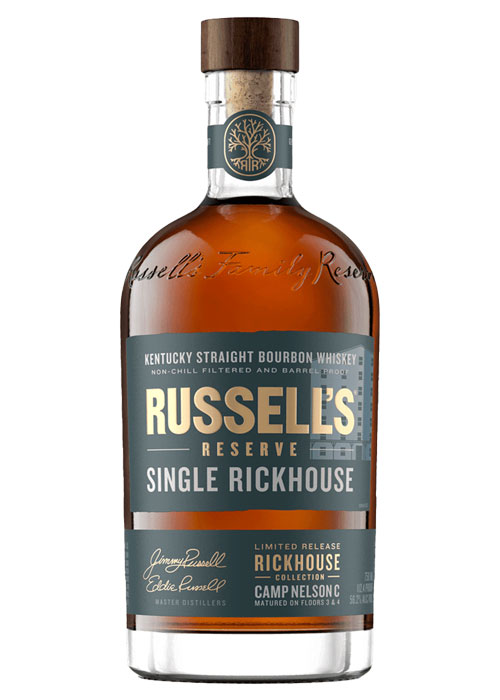

So it’s no surprise that in the summer of 2022, when fans caught wind of the Russell’s Reserve Single Rickhouse Camp Nelson C label filing, speculation started circulating. How many bottles are going to be produced? Can anyone really taste the influence of the warehouse where the whiskey has been aged? Or is this just a clever marketing maneuver to get bourbon nerds to fork out more cash, and perhaps the beginning of a new movement in the ever-evolving American whiskey landscape?

The Cult of Wild Turkey and the Mythology of the Rickhouse

Russell’s Reserve is a line of premium bourbon and rye whiskeys produced by the Wild Turkey distillery. It’s named after one of the royal families of Kentucky bourbon, father and son master distillers, Jimmy and Eddie Russell. Eddie’s son, Bruce Russell, has also been working his way up the ranks, setting things up for what looks set to become a three-generation distilling dynasty.

Like any legacy distillery in Kentucky, Wild Turkey has a sizable contingent of hardcore fans — people who seek out every new release, go hunting for old bottlings, and compare tasting notes online.

To understand the relationship between single-barrel whiskeys and the warehouses they’re aged in, look no further than Blanton’s. In 1984, at the distillery that would later become Buffalo Trace, master distiller Elmer T. Lee introduced the first-ever whiskey marketed as coming from a single barrel. Lee’s mentor, Colonel Albert B. Blanton, believed that the best bourbon the distillery produced — the so-called “honey barrels” — were aged in the now-venerated Warehouse H. As a tribute to Blanton, every bottle of his namesake bourbon is still aged in that rickhouse to this day.

The eventual success of Blanton’s changed everything. Single-barrel bourbon caught on and is now a major part of the American whiskey landscape.

“The only word to describe the growth in single-barrel whiskey is explosive,” says Jay West. Also known online as t8ke, West runs one of the largest single-barrel programs for the Reddit community r/Bourbon and reviews bourbons on his website Whiskey Raiders. West selects around 150 barrels per year and tastes samples from about 1,000 individual barrels annually when considering them for the program.

Single-barrel whiskey captures a snapshot in time of the alcohol a distillery produces and, most importantly for collectors, each barrel is unique and limited. “There are only about 200 bottles that come from a single barrel,” says West. “They’re sharing this with just a handful of other people. There’s nothing else like it.”

From there, the idea that certain rickhouses had some magic ability to influence the liquid in the barrels to mature exquisite whiskey spread and there was no way to put it back in the bottle.

Wild Turkey had been releasing a single-barrel bourbon, Kentucky Spirit, for some time, but in 2014, the newly launched Russell’s Reserve private barrel program marked a major shift for the company. The program began as a way for Eddie Russell to share individual barrels that had a special or unique flavor profile and grew to become a source of exclusive barrel picks for restaurants, liquor stores, and bars all over the country. Fans of the distillery had something new to obsess over.

Over time, Wild Turkey enthusiasts realized that these barrels had some very different and noticeably unique flavor profiles that varied significantly depending on where the whiskey was aged. David Jennings, blogger and author of “American Spirit,” the history of Wild Turkey, was at the vanguard of this movement, sharing what information he could find about where each individual barrel came from on his website.

“People pay attention to the warehouse because there actually can be a significant flavor difference from rickhouse to rickhouse,” Jennings explains. Pieced together from the information given out by the distillery on each bottle, Jennings and other fans started to map out which barrels came from which warehouse, and worked on comparing tasting notes. With Jennings at the lead, the community worked to build a better understanding of just how much the location where a whiskey is aged matters.

Wild Turkey is uniquely suited to be a case study for the effects of warehouses. The distillery uses only one strain of yeast and two mash bills, one for all of its bourbons and one for its rye whiskeys. The differences in flavor between the distillery’s products come from the maturation process, blending, and proof. “The rickhouse is a piece of the puzzle,” says West. “In an age where people are looking for more and more information and brands are making it more available, folks are finding that those details matter.”

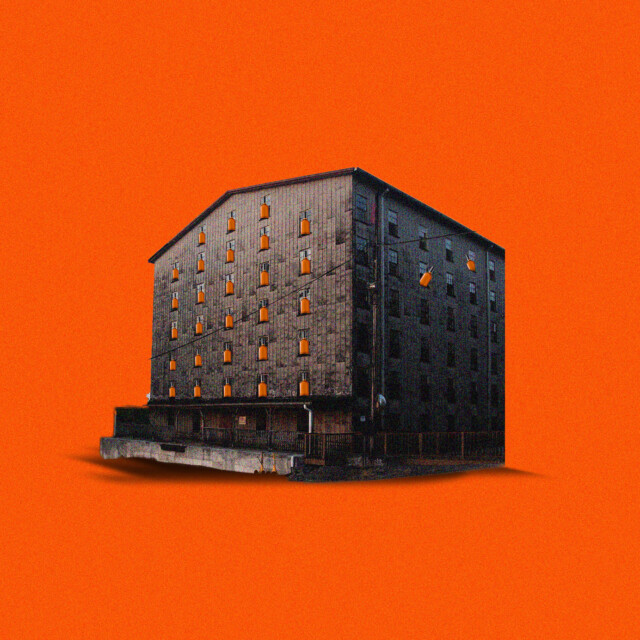

Russell’s Reserve Single Rickhouse Camp Nelson C was finally released in fall of 2022 to widespread acclaim. The name references one of the locations in which Wild Turkey ages its whiskey — warehouses that are spread across three campuses: McBrayer, Tyrone, and Camp Nelson, which are all located throughout Anderson County, Ky. Each campus is comprised of multiple rickhouses and is geographically separate, meaning each campus is subject to slightly different microclimates that affect the maturation process. “At Camp Nelson, those warehouses kind of sit out on their own and get a lot of heat,” Bruce Russell says. “They’re typically higher proof than the rest of our warehouses and [the whiskeys] typically trend sweeter.”

Jennings and the private barrel faithful are in consensus that bourbon from Camp Nelson often has a dessert-like confectionary flavor profile and there’s a tendency for the whiskey to have a prickly spiciness on the palate similar to Dr. Pepper or Coca-Cola.

When it comes to obsession over production nuances, Wild Turkey is not alone. Bourbon drinkers are becoming more educated across the board. And as they learn more about whiskey production, their thirst for detailed information rivals that for the whiskey itself.

“Every day our team receives emails from consumers requesting any details we can provide them about their specific bottles,” says Susannah Hubler, Barrel Select experience manager at Buffalo Trace. “They want to know all the information about where it aged, how old the bourbon is, the recipe, when the barrel was filled, etc. ”

Because of how educated customers have become, distilleries can now take more chances with unique and experimental bottlings that in past decades likely wouldn’t have made it past the brainstorming phase. “We actually dig how knowledgeable and how into our products people are,” says Russell. “It allows us to get nerdier with our releases.”

The Russell’s Reserve Single Rickhouse is an example of this. Without the hardcore bourbon enthusiasts and their fascination with the different campuses and warehouses, there wouldn’t be a viable market for a product like this. It’s a cyclical process. The more production details that are shared, the more drinkers learn, and the more they want to know.

Do warehouses actually make a difference?

The standard operating procedure in the American whiskey industry is blending. Each bottle contains distillate aged in multiple barrels in different rickhouses. The aim is consistency — consumers generally expect each bottle they pick up at the store to taste the same as the last one they purchased. Distilleries purposefully pull barrels from many different warehouses in order to match their target flavor profile.

Since bourbon is required by law to be aged in brand-new, charred oak casks, the most impactful variables in the aging process are environmental. Changes in temperature, humidity, and airflow all play a factor, and the warehouse itself can actually play a role in maturation as well. “Each warehouse has its own personality based on location, construction (brick or metal), size, [number of] floors, and heating,” says Buffalo Trace’s master distiller, Harlen Wheatley.

“They’re all built a little bit differently,” Bruce Russell adds, describing Wild Turkey’s warehouses. “Some of them have different floors, and some of them are turned differently so the sun is going to set and rise on different sides. Some are turned so they get a lot of wind. Having a lot of airflow is really good for your barrels.”

Even within an individual warehouse, not all barrels age equally. Heat naturally rises inside the buildings, so the barrels on higher floors rest in a warmer environment. This speeds up the extraction of flavors from the barrel slightly. Of course, distillers anticipate and plan for these variances. “We know the best place for a 10-year whiskey, for example,” says Wheatley. “We know we can’t put a 23-year-old barrel on the top floor because it would age too quickly.”

Many who have experience with blending whiskey or selecting single barrels believe that barrel-to-barrel variation is more pronounced than variation between rickhouses. That sentiment is echoed by Fred Noe, seventh-generation master distiller at James B. Beam Distilling Co. “Two barrels sitting side by side in the same rackhouse can have vastly different flavor profiles,” he says. “Although we don’t think certain warehouses produce more highly regarded whiskey than other warehouses, we have found that individuals prefer barrels aged in certain locations based on their taste preference.”

That variation between barrels is what makes the concept of a single-rickhouse blend compelling. By mixing a small number of barrels from one rickhouse, Wild Turkey is mitigating the barrel-to-barrel variances and creating a profile that represents the unique attributes that a specific warehouse imparts to the whiskey aged within it.

Is Single Rickhouse the next big thing?

Bottling a whiskey blended from barrels aged in one individual rickhouse is extremely uncommon. Marketing a bourbon as such is even more uncommon, but it has been done before — even by Wild Turkey.

As part of the Master’s Keep series of limited-edition, experimental whiskeys, the distillery released the Australia-exclusive Master’s Keep 1894 in 2017. All the barrels blended in this whiskey were pulled from Tyrone A, which, in 1894, was the first warehouse built by the distillery. Buffalo Trace has also released a few E.H. Taylor, Jr. bottlings that the distillery says were pulled from the same warehouse.

But the Russell’s Reserve Single Rickhouse signifies a shift in both the marketing and consumption of bourbon. Innovation in premium whiskey is now being driven by hyper-educated enthusiasts.

So what comes next? Wild Turkey has already announced that Single Rickhouse will continue to be released as an annual bottling, with Camp Nelson F slated for a 2023 release. In that sense, the concept is here to stay. What remains to be seen is whether or not other distilleries will introduce something similar.

“I would be really surprised if another distillery didn’t put out something like this,” says Russell. “Right now, everyone in the industry is looking to just put stuff out because people are buying it. Now is the time for innovation.”

Intrepid bourbon enthusiasts recently found an interesting Knob Creek label that was submitted for approval to the TTB. It looks quite similar to the classic Knob Creek 9-year label except for one small difference: a small emblem on the label that reads “Featuring Rackhouse L.” Does Knob Creek have the next single-rickhouse bourbon in the pipeline?

Apparently not — or not for now, at least. The “Rackhouse L” labels are still for single-barrel bourbon. “This specific bottle is part of our Longhorn Steakhouse Knob Creek series,” says Noe. “Our distillery team hand-selects single barrels for them on an ongoing basis, but outside of this selection, this isn’t super common for us right now.”

The master distillers of Buffalo Trace and Jim Beam don’t currently have plans to introduces single-rickhouse blends. But somewhere down the road? Both Noe and Wheatley have the same answer: In the bourbon industry, never say never.