Far below ground in Louisville lies a room out of time. It’s cavernous, dotted with support columns, its ceiling vaulted into a dozen or so apexes. A section of the ceiling is lined with intricately painted leather. Remaining surfaces are lined with Bavarian-themed Rookwood pottery dating to 1907. It is here in the Rathskeller Room, the story goes, where a young lieutenant named F. Scott Fitzgerald found inspiration for “The Great Gatsby.”

Several floors above sits a small dining room, built for poker and billiards, where a secret door leads to a hidden staircase and subterranean tunnels. Legend has it gangster Al Capone and bootlegger George Remus used the room for gambling — and quick escapes at the first sign of trouble.

The veracity of these tales is debated. The hotel where they took place, however, is intact and alive as ever.

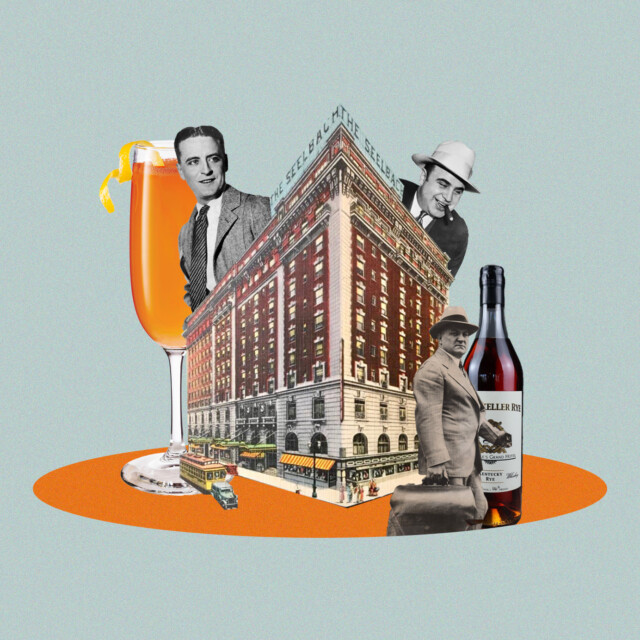

Sitting at the corner of 4th Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard, blocks from “Whiskey Row,” sits The Seelbach Hotel. Its Prohibition-era history is enough to cement it firmly in American alcohol history. But the Seelbach’s boozy ties didn’t stop with the 21st Amendment.

Its namesake Seelbach Cocktail took the mixology world by storm after its pre-Prohibition recipe was “rediscovered” at the hotel in 1995. Two decades later, the backstory was revealed to be one bartender’s elaborate hoax.

In 2007, the hotel’s bar acquired single barrels of bourbon and rye from Bardstown’s Willett Distillery. Dubbed “Speakeasy Select Bourbon” and “Rathskeller Rye,” most of the stock was sold on premises by the pour. A scant few bottles made their way into wider distribution and today command resale prices sometimes north of $20,000.

The story of the Seelbach is a story of Louisville’s continued place as a focal point of whiskey culture. As with so many stories surrounding aged spirits, it’s an ongoing chronicle of tales both tiny and tall — almost always with a kernel of truth.

Louisville’s (Original) Grand Hotel

Built by Bavarian-born brothers Louis and Otto Seelbach, the Seelbach opened in May 1905 with about 150 rooms, just in time for that year’s Kentucky Derby. The hotel immediately proved popular, and the brothers expanded to around 500 rooms two years later. It has since hosted dozens of distillers, hoards of celebrities, and (at least) nine U.S. Presidents.

From 1926 through the mid-1970s, the hotel changed owners (and names) several times. A 1975 ownership bankruptcy led to its closure, and in 1978 it was purchased by actor and developer Roger Davis, a Louisville native. The hotel reopened to guests in 1982, and eventually sold again and rebranded to the Seelbach Hilton Louisville.

The explosion of bourbon tourism renewed interest in the hotel’s history, particularly its (alleged) ties to Prohibition-era crime. Those stories center on two figures: legendary crime boss Al Capone, and “King of the Bootleggers” George Remus, who likely served as an inspiration for the character of Jay Gatsby.

“I’ll never say that Al Capone was at the hotel. I say that he was a possibility. … it just makes sense that the city of Louisville and the Seelbach Hotel would have been a great stopover for any of the gangsters.”

“The explosion of bourbon came about … and the stories of Al Capone and George Remus all came to life that much more,” says Larry Johnson, the Seelbach’s hotel historian. Johnson has worked at the hotel since 1981. In 2005, he wrote “The Seelbach: A Centennial Salute to Louisville’s Grand Hotel.”

While a common local adage claims Capone and Remus used the Seelbach as a gathering point, Johnson says there is little evidence to prove it. After all, it’s not as if mobsters kept public records. But as a center for local wealth, it’s easy to imagine well-to-do bootleggers stopping by for some impolite company.

“I’ll never say that Al Capone was at the hotel,” Johnson says. “I say that he was a possibility. … It just makes sense that the city of Louisville and the Seelbach Hotel would have been a great stopover for any of the gangsters. It was known at the time for having the best billiards and poker room in the Midwest.”

Preserved today, that game room has a secret door that leads to two different sets of tunnels beneath the hotel. Johnson says the motivation for a clandestine passageway dates to well before Prohibition hit Kentucky.

“The stairs from the poker room were built in 1908, before Prohibition,” he says “That’s not to say they didn’t have something like that in mind; it was an ideal getaway. If there had been a game going on with a lot of money swapping hands, and an irate wife came in, what better way to get away than one of the two sets of tunnels.”

The Great American Author

For about a month in early 1918, a young Army lieutenant named F. Scott Fitzgerald was stationed at Camp Zachary Taylor near Louisville. It’s likely Fitzgerald and fellow officers visited the Seelbach to drink and cavort with young women. What happened next depends on which legend you subscribe to.

“To walk into the lobby of the Seelbach was to walk into infinite possibility,” writes Rebecca Rolfes for “The Bitter Southerner. “In 1918, hotels were still special places, the province of the wealthy and glamorous.”

Some claim it was here that the 20-year-old Fitzgerald met 40 year-old George Remus, sparking a friendship that would eventually inspire the titular character in “The Great Gatsby.”

“Every single thing that came across Fitzgerald’s desk or kitchen table was fodder for his writing. What somebody said. How a drink was made. … Probably the hotel he ends up writing about was a combination of lots of hotels.”

Other reports say Fitzgerald was kicked off the premises three times for public intoxication, quite the feat given the four-week duration of his Camp Taylor stay.

As Rolfes emphasizes, it’s difficult to nail down the specifics of Fitzgerald’s social time in Louisville. “Much of the speculation about Fitzgerald’s inspirations and their Seelbach connection is exactly that, speculative hindsight.”

According to Dr. Kendall Taylor, a biographer who has written two books on F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, it’s impossible to deduce exactly how the Seelbach influenced subsequent writing. But the ties are clearly present and, as Taylor notes, there’s immense power in conjecture.

“Every single thing that came across Fitzgerald’s desk or kitchen table was fodder for his writing,” Taylor says. “What somebody said. How a drink was made. … Probably the hotel he ends up writing about was a combination of lots of hotels. … So it infuses his writing, as every single thing did.”

Unlike Prohibition bootleggers, novelist Fitzgerald had a penchant for leaving clues. On at least two occasions, his writings mention the Seelbach Hotel by name.

Published in 1925, Gatsby makes nearly a dozen mentions of Louisville as the home of Daisy Buchanan. One passage names the Seelbach (or “Muhlbach Hotel,” depending on the edition) as the site of her and Tom’s marriage:

“In June she married Tom Buchanan of Chicago with more pomp and circumstance than Louisville ever knew before. He came down with a hundred people in four private cars and hired a whole floor of the Seelbach Hotel…”

Dr. Taylor also cites a 1929 piece for The New Yorker titled “A Short Autobiography,” in which Fitzgerald gives a yearly chronology of drinking escapades. The entry for 1918 reads simply, “The Bourbon smuggled to officers’ rooms by bellboys at the Seelbach in Louisville.”

The Seelbach itself has occasionally leaned into the novel’s mention. Located just off the hotel’s lobby, “Gatsby’s on Fourth” offers a buffet breakfast seven days a week.

A Hoax of Historic Proportions

For decades, Louisville’s Brown Hotel generally eclipsed the Seelbach in national popularity, despite it opening 15 years later. That was largely thanks to the Hot Brown, an open-faced sandwich invented at the Brown as a lavish hangover cure.

That changed in 1995, shortly after Adam Seger was named bar manager at the Seelbach. While digging through old menus, Seger stumbled upon a bourbon and Champagne cocktail from 1912:

- 1 oz bourbon

- ½ oz triple sec

- 4 dashes Angostura bitters

- 3 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

- Chilled Champagne, to top it off

Seger claimed the recipe originally resulted from an accidental spilling of Champagne into a Manhattan. Driven by the story, the Seelbach cocktail became a smash hit.

That story, it turns out, was a hoax. Roughly 20 years after “rediscovering” the drink, Seger admitted he’d made the entire backstory up, as detailed by Robert Simonson for The New York Times. There was no original recipe, and no accidental concoction. The drink was Seger’s original — more contemporary — creation.

“What we’re trying to do is help people navigate through these fake stories and prioritize transparency. So I thought it was a good tie-in to what we’re trying to do.”

“It really caused quite a stink in Louisville when that came out because it was such a famous cocktail,” says Heather Wibbels, a Louisville-based mixologist. “It is very common that the stories behind the creation of a cocktail are not true, or they’re added on to a very thin fact … We all know people will remember a story more than they’ll remember a fact.”

The cocktail’s fictitious past hasn’t slowed its popularity, especially locally. It remains a top draw to the Old Seelbach Bar.

“It’s a hoax and a well-weaved story, but I don’t think that it takes away from the interesting aspects of the drink,” says Jordan Long, bar manager at the Seelbach. “I think it’s a fun thing to tell guests, and it’s a fun drink.”

The unraveling of the cocktail’s myth did have an additional impact on the American spirits landscape. It inspired the name for an online retailer, Seelbach’s.

“It was really the cocktail story I ended up hearing about, and I thought it was a funny story,” says founder Blake Riber, who started the site soon after the cocktail hoax came to light. “What we’re trying to do is help people navigate through these fake stories and prioritize transparency. So I thought it was a good tie-in to what we’re trying to do.”

Riber’s Seelbach’s platform specializes in products from craft distilleries, selling and shipping directly to consumers. While his site shares a name with the hotel, Riber says their lines of business are too different to warrant any issues.

“I thought I’d hear something from the hotel, but I never have,” he says. “When the attorneys looked at it, they saw a trademark for what the hotel has, but there was nothing involving online commerce.”

Single Barrel Gold

In 2007, the Seelbach bar selected two single barrels of whiskey from Willett Distillery in Bardstown, Ky. One was a 14 year-old Kentucky straight bourbon with a distillation date of Jan. 28, 1993; it yielded 164 bottles.

The other was a 23 year-old Kentucky rye — almost preposterously old by today’s standards — with a distillation date of April 19, 1983, yielding 211 bottles. (That’s the same distillation date as the now-famed Red Hook Rye.) At the time, Willett wasn’t actively distilling, and the picks came from its collection of barrels from undisclosed sources. Even today, unconfirmed rumors on sourcing abound in tasting groups and on whiskey forums.

Most of the bottles were sold by the pour at the Seelbach bar or through room service. Some made their way to Washington D.C.-area bars, including Jack Rose, or into private collections.

Today, Speakeasy Select Bourbon and Rathskeller Rye are among the most expensive bottles of American spirits ever sold at auction. In February 2022, an authenticated bottle of Speakeasy Select sold for over $17,000. In December 2022, a bottle of Rathskeller Rye sold for over $24,000.

The hotel’s own stock of the treasured whiskey is long gone. For Long and other current employees, the auction prices are as much a source of humor as they are of pride.

“We see the auctions, and we laugh about those bottles going for so much,” Long says.

The Seelbach Today

Today’s Seelbach Hotel features 321 guest rooms, offers 32,000 square feet of meeting space, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It remains one of the city’s prime spots for lodging with a rare mixture of convenience and stateliness.

As the hotel’s historian, one of Larry Johnson’s main goals is to inform guests the hotel is an attraction itself. Part of that draw is enjoying hospitality in the same rooms and bars famous outlaws may or may not have patronized.

“The hotel itself has been not only a great place to stay for 100 years, but it’s a great place to taste whatever spirit or drink you wanted,” he says.

It’s a sentiment echoed by other members of the staff.

“When I have guests come in, I tell them it’s best not to compartmentalize. The hotel as a whole, food, beverage, with all its units, shines the best,” Long says. “And I always recommend they go see Larry.”