On May 26, 1913, Theodore Roosevelt sat in court in Marquette, Michigan, watching man after man declare on the stand that he was not, and never has been, a drunk. He must have been pleased, because Roosevelt — everyone’s favorite mustachioed, quote-spewing, Rough-Riding president — was ready to take anyone to court who said he favored a drink or two.

“Roosevelt lies and curses in a most disgusting way,” the Iron Ore newspaper wrote on October 12, 1912, with a presidential election less than a month away. “He gets drunk, too, and that not infrequently, and all his intimates know about it.”

That was the turning point for Teddy. Like another, more recent, presidential candidate who avoids alcohol and is quick to sue, Roosevelt went after the press. He sued the editor of the Iron Ore, George Newett, for libel. Riding into the courthouse with a wave of supporters from the train station he arrived at, the Theodore Roosevelt Center writes, 54-year-old Roosevelt made his case that he does not, in fact, drink to excess.

“I ask you, since your arrival at the age of manhood, what is the fact as to whether you have ever been under the influence of intoxicating liquors or drugs?” the court asked Roosevelt.

“I have never been drunk or in the slightest degree under the influence of liquor,” Roosevelt replied.

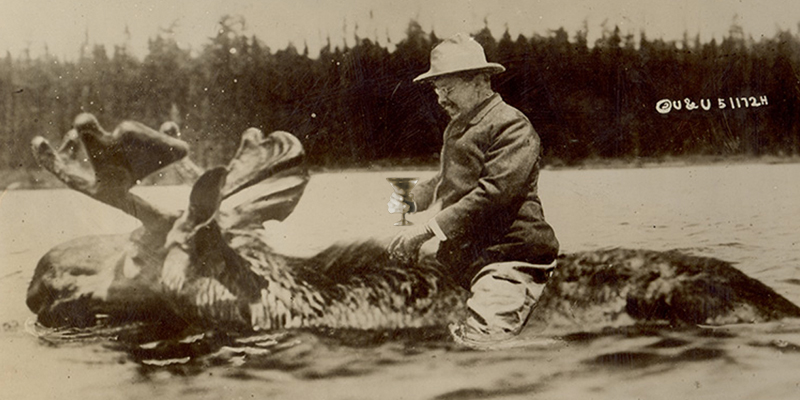

Roosevelt’s manhood came from riding into Cuba with the Rough Riders, shooting wild game in Africa,and boxing in underground matches he arranged at the White House. It even came from edited photos of him riding a moose. It did not come from drinking whiskey, brandy,or beer (he did admit to occasionally drinking light wine, however).

“I have never drunk a high-ball or cocktail in my life,” Roosevelt told the court. “I have sometimes drunk mint juleps in the White House. There was a bed of mint there, and I may have drunk half a dozen mint juleps a year, and certainly no more.”

A mint julep is, of course, a cocktail. But mint is good for you, right? At least in moderation.

“I never drank but one mint julep at a time,” Roosevelt said. “I doubt if I have drunk a half dozen a year; I doubt if I drank a dozen during the entire seven and a half years there since I left the presidency. In the four years since I left, I remember I have drunk two.”

One of those two times, Roosevelt “simply touched a mouthful” of the mint julep, and the other time he only drank from a cup that was passed around state governors. The trial was, as all things Teddy Roosevelt, a massive affair.

“BARS ALL RUMOR ABOUT ROOSEVELT,” The New York Times headlined a story about the trial. “Correspondent’s denial of tippling story causes five-hour battle between lawyers.”

The defense, The Times writes, was counting on people showing up and calling Roosevelt a drinking man. If enough people believed that, the paper could claim it printed a common belief. Instead, more people showed up to support Roosevelt.

Being considered a drinking man in 1913 was quite a feat. According to data from the National Institutes of Health, 2.56 gallons of alcohol were consumed per capita from 1911 to 1915. Roosevelt’s claims he made in the court room wouldn’t make him a drinking man today, let alone in that heavier-drinking era.

Roosevelt ended up winning the libel suit against Newett, continuing the power of “The Roosevelt Way” that started when he broke from the Republican party to run as an independent presidential candidate. The Roosevelt way, the Iron Ore said in the same libelous article, is that Roosevelt “is the only man who can call others liars, rascals and thieves, terms he applies to Republicans generally,” despite the fact that “all that Roosevelt has gained politically he received from the hands of the Republican party.”

Politics aside, drinking light wine and mint juleps isn’t a terrible habit. But if you take Roosevelt’s drinking habits on as your own, don’t try to get out of calling a mint julep a cocktail.