Bourbon is America’s spirit. The spirit surged so much in recent years, the number of bourbon barrels in the state of Kentucky is almost double that of its human residents. But that wasn’t always the case.

In his exhaustive history of America’s on-again, off-again, ridiculously on-again relationship with bourbon (“Bourbon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of American Whiskey”), author Fred Minnick makes note of one unexpected bourbon success story in the 1980s: “Other than a few brands going strong, bourbon’s best domestic story of the late 1980s was Rebecca Ruth candy maker, who was making bourbon candies and appealing to the American sweet tooth.”

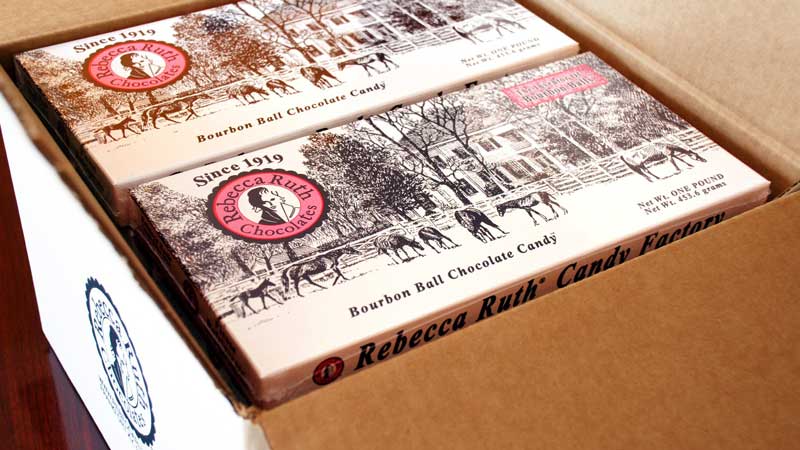

Those candies are called Bourbon Balls, and they were actually invented back in 1938, not by “Rebecca Ruth,” but by Ruth Hanley Booe, one half of the pair that founded the Rebecca Ruth candy store about 20 years earlier. (The candies were created by Ruth Hanly Booe in 1938 after Rebecca left the business. The candy store itself was created in 1919.)

Rebecca Ruth Candy was founded in 1919 by two women — two unmarried, part-time teachers in Kentucky, to be exact: Rebecca Gooch and Ruth Hanly (later Ruth Hanley Booe). Like many women of their day, Gooch and Hanly Booe gave candy as presents. And at some point in 1919, it must have occurred to them that they were better at molding chocolate than molding young minds, because they left chalkboards and abacuses and other old-timey educational tools behind to found Rebecca Ruth Candy — today, known as Rebecca Ruth Chocolates.

Perhaps serendipitously, the two founded their store right as Prohibition took hold, so their storefront was actually the now-defunct barroom of the Frankfort Hotel. At a time when women were hardly encouraged to found, let alone run, their own businesses, Gooch and Hanly Booe chose to call their shop “Rebecca Ruth” to honor and preserve the identity of the jointly female-founded business.

“This was an era when even the few women who did go into business for themselves usually did so with the financial backing of a husband,” Fiona Young-Brown writes in her book, “A Culinary History of Kentucky.” She continues: “Ruth and Rebecca were both single and determined that they did not need husbands to provide for them. Together, they decided to forge a business partnership. Rebecca-Ruth Candy was born. It was a decision that would earn them strong support from some quarters and equally strong ridicule from others.”

Social norms being the shortsighted identity restraints that they are, Gooch and Hanly wisely pressed on. Young-Brown describes their “gumption” in getting the word out about their candies (and what’s more old-timey than gumption?): “According to company history, it was not unusual for one of them to approach a complete stranger on the street to sing the praises of Rebecca Ruth.” In other words, they were early practitioners of guerrilla marketing and social influencing.

Here’s where the (imaginary) movie script meets some real life drama: Ruth Hanly left the business for a time after getting married and having a child, but early and sudden widowhood found her returning to Frankfort, where she ended up taking over the business. This time, Rebecca Gooch married and sold her shares to Hanly Booe. Again, in the movie version of this, there’d be a big montage of the young widowed Hanly Booe having an awkward time setting up her candy business as a single mother (baby smears his face with chocolate, baby smears her face with chocolate, a guy played by James Marsden shows up and says something snarky but cute like “Sweet things make me gag,” etc.).

In real life, it was a dark, punishing struggle for Hanly Booe to keep her business afloat. On the curtails of her widowhood, the Great Depression hit the United States in 1929. Chocolate was no longer a commodity, and banks were not prioritizing lending capital to a widowed single mother with a boutique candy business. But — not a spoiler if you’re paying attention — the business prevailed.

By 1936, right around the time of the town of Frankfort’s 150th anniversary celebration, Hanly Booe was still struggling to make ends meet. Her deus ex machina came in the form of a visitor who suggested an idea for a perfect candy: add booze.

According to both Young-Brown and Hanly Booe’s grandson, Charles Hanly Booe, the visitor was a dignitary visiting Kentucky named Eleanor Hume Offutt, who told Hanly Booe “the two best tastes in the world [are] a sip of Kentucky bourbon” and a bit of Hanly Booe’s own chocolate. Of course, Hanly Booe listened (it just seems reckless not to listen to Eleanor Hume Offutt).

Within two years, Hanly Booe perfected her recipe for Bourbon Balls. No shock, the candy “was an instant hit,” writes Young-Brown. “By the time World War II rolled around, even rationing could not stop Rebecca Ruth. Loyal customers saved their sugar rations to share with Ruth.”

As for just what makes the Bourbon Balls so special, that’s a carefully guarded secret that candy and bourbon lovers are still a bit obsessed with. As recently as 2018, Ruth Hanly Booe’s grandson, Martin Booe, described the candy in Epicurious as a “whiskey-spiked cream center enrobed in dark chocolate and topped with a pecan.” Since conflict is good for any script, it should be noted that, according to Martin Booe, it was actually the Kentucky Gov. Ruby Laffoon (a man) who inspired Hanly Booe to create the Bourbon Ball, remarking at some point during that same Frankfort 150th anniversary that “there was no better taste than a bite of chocolate followed by a sip of bourbon.”

Whoever inspired the idea, the most important question remains: What bourbon is inside the candy? Evan Williams 100-proof, “no more than 5%” of the contents of the filling, according to A Taste of Kentucky. (No, the bourbon isn’t cooked off but also no, you can’t get buzzed off of them. We’ve tried.)

However, Rebecca Ruth also makes custom bourbon candies for other distillers, including Maker’s Mark and Buffalo Trace. And out of 5 million total pieces of candy produced by the company each year, 3 million are Rebeca Ruth’s famous Bourbon Balls. (This is probably about as many as you’d need to get a karaoke-worthy buzz).

Whoever actually gave Hanly Booe the idea, her Bourbon Balls may be the sole sugar-coated, continuous link in unbroken bourbon appreciation in America from the year 1938 through to the present day. They’re also testament to a real-life story of a woman and single mother who, alone at the helm of a marginal luxury business with a small child and no one to “save” her, never forgot one vital piece of wisdom: When life hands you lemons, you should pelt them at passing cars, because the answer is almost always whiskey and chocolate.