As recently as five years ago, the terms “craft beer, “microbrew,” or even “cerveza artisanal” were not commonplace in Puerto Rico. They still aren’t: Costly import taxes, regulatory roadblocks, and natural disasters make running any business here challenging, let alone one most Puerto Ricans don’t see as a necessity.

But thanks to establishments like La Taberna Lúpulo bar in Old San Juan, recognition of small-batch brewing is growing. To enter Lúpulo, meaning “hop” in Spanish, is to encounter the unexpected: Coolers are stuffed with the likes of Orval, and taps flow with Bell’s Hopslam. Co-owner Zalika Guillory has worked hard to get the most sought-after mainland craft brands and Trappist imports from Europe. Mostly, though, she wants to show off local brands, which she pours on 40 to 60 percent of the bar’s 38 taps.

“It’s important for Puerto Ricans to know people here are contributing [to the beer scene] and doing it in a way that’s uniquely Puerto Rican,” Guillory says. Lúpulo, along with the island’s 13 craft breweries, is doing just that.

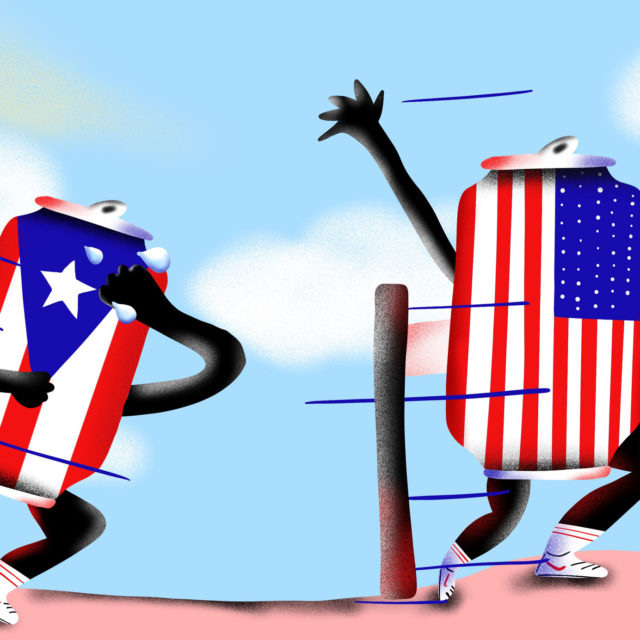

While Guillory and a handful of fellow publicans are properly serving and promoting their island’s offerings, owners of craft breweries here struggle mightily to compete with imports and the commonwealth’s main mass-produced lager, Medalla Light.

“The U.S.-based craft products brought down to the island are way cheaper to produce,” Juan Cruz, owner of Zurc Bräuhaus Craft Beers brewery in Coamo, says. “And paperwork is time consuming in multiple orders of magnitude higher than it should be.”

Puerto Rican brewers incur prohibitive expenses to get supplies onto the island and to distribute beer to 5,000 licensed retail outlets within its borders. Adding to their troubles, small brewers contend that public officials, used to dealing with “big pharma” and — before it moved off-island — big agriculture, remain suspicious and restrictive toward small businesses like theirs.

To craft their Helles lagers, passion fruit IPAs, and coffee stouts, Puerto Rican brewers have to import nearly every ingredient, including grains and hops, as well as equipment. No inputs, save for some fruit and vegetable adjuncts, grow locally.

THE HIGH COST OF DOING BUSINESS

On top of normal freight costs comes the Jones Act, signed in 1920, which requires that all goods shipped between U.S. ports be transported on vessels that are built, owned, and operated by U.S. citizens. This creates a scenario where shipping companies can charge higher rates because of lack of competition. Thus, a cottage brewer on a U.S. island looking to procure modest orders of Idaho barley and hops pays an elevated price to have those ingredients shipped (one study found it costs twice as much to ship a container to Puerto Rico from Florida than from a foreign port). Add an 11.5 percent port tax, and beer gets pricey real quick.

Still, Lúpulo’s Guillory says a standard keg (15.5 gallons) of California’s Russian River costs $180 in states where it’s sold, while liquid made in San Juan can carry up to a $160 price tag per sixtel (5.16 gallons). Why? Guillory says Puerto Rico pays more than mainlanders for transportation, fuel, water, electricity, and interest rates. “And in terms of keeping beer cold, we’re in the tropics,” she says.

This partially explains why, according to wholesaler Joey Maldonado, local brew only comprises 1.2 percent of Puerto Rico’s beer market, which Cruz says translates to $17 million in annual economic impact. This contribution is in stark contrast to mainland states. Even Wyoming, which reaps less from its craft brewing industry than any other state, posted a $192.6 million direct contribution last year.

Despite the nearly negligible competition, the big guys are playing the price-war game to maintain dominance. “You can find Medalla at one buck, Heineken, two for $3,” says Maldonado, who sells crafts and locals through a distributor called Ballester Hermanos. “I’ve never seen that before.”

Representatives for Medalla didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Brewers did get some relief last summer, when former governor Ricardo Rosselló signed an excise tax reduction into law. Put into effect Oct. 1, the new law drops the per-gallon tax from an exorbitant $2.55 to $0.95. Cruz, who led lobbying efforts for the bill, hopes the new rate will raise annual economic impact to $261 million. “It’s a step into the right direction and will give us a fairer competitive profit margin versus imported products,” he says.

The bill succeeded because in a unique display of solidarity, 11 craft brewers formed a loose association in 2018, and seven producers later brewed their first collaboration to raise money to fund some of their lobbying activities.

TACKLING REGULATORY HURDLES

In the summer of 2017, Jose Luis Diaz Vazquez and his wife, Sarahil Nieves, spent their life savings to upgrade the cramped 2.5 barrel nano-brewery they own in their mountainous hometown of Utuado. Two months later, in September 2017, Hurricane Maria hit. “We lost everything that we had,” he says. “We lost all the beer, grains, hops, and all four fermenters. We were prepared for everything except a disaster like this.”

Despite long stretches without electricity, water, telecommunications, a working generator, or access in and out of town, the owners of REBL Brewery produced a batch of beer within two months. Then, Diaz Vazquez says, “In May 2018, things were sort of back to normal. In November 2018, we were seeing things getting better.”

Then, in December of 2018, “Hacienda gave us another hurricane,” Diaz Vazquez says, referring to Departamento de Hacienda, Puerto Rico’s tax agency regulating alcohol production. Hacienda shut REBL down for three months while the agency updated its accounting system, according to Diaz Vazquez.

Two emails requesting comment from Hacienda went unanswered.

“When we finally got approved, we had to dump what was in the fermenter,” Diaz Vazquez says. Given that Hacienda agents have to be on site whenever product gets packaged or leaves the building, and that they hold the keys to open locked fermenters, timing can be critical. Multiple brewers say that they have been forced to dump spoiled batches waiting for agents to visit.

But as the aftermath of Hurricane Maria showed, Puerto Ricans are nothing if not optimistic and scrappy, and no breweries closed permanently because of the storm — or due to regulatory hurdles. As craft breweries emerged from the literal muck to present post-storm beers, bar owners have shown gratitude and loyalty. Diaz Vazquez says patrons of one bar cheered when he delivered the first keg of his flagship, Kasiri IPA, in early 2019.

Rhaiza Casiano Pabón, of the Cabo Rojo-based brewery Pura Vida, says when she hosts bar events, her beer sells out in less than two hours. Pura Vida, like most of the others, doesn’t have a tasting room, and none of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries can yet afford to sell on the mainland. So for now, the success of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries is totally reliant on local support. “The bars [here] try to give us an opportunity,” Pabón says. “They are open minded to the fact that people want to try craft beers.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!