Twenty years ago, what we consider today as “natural wine” was hardly known. It was a niche movement that existed as a more or less private alignment of like-minded producers, supported by a network of Parisian wine bars. It was counter-culture. Almost covert. If you knew, you knew.

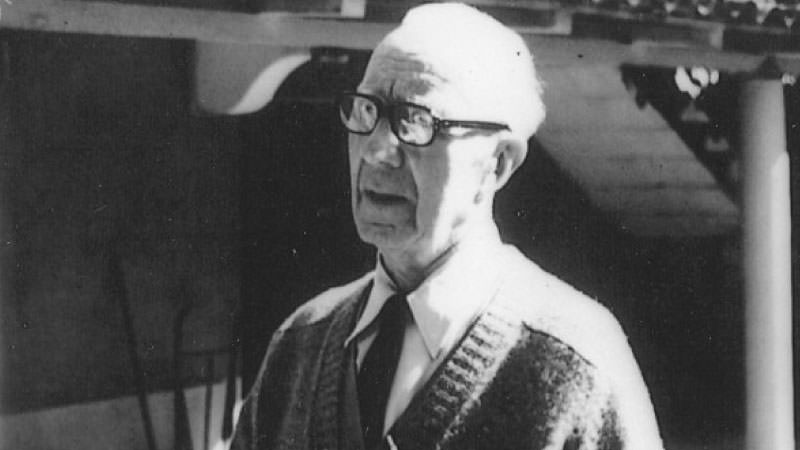

I found out about natural wine from internet bulletin boards in the late 1990s. It was strange, mysterious, and as a newbie wine geek it caught my imagination. Here were impassioned winegrowers keen to do as little as possible to their wines. The movement had largely grown out of France. Vignerons, inspired by the work of Beaujolais-based scientist and winemaker Jules Chauvet in the 1970s — who worked hard to devise no-addition winemaking protocols — began making wines without the safeguard of sulfur dioxide additions, which at the time were almost universal.

Back then, natural wine, despite the lack of a formal definition, was radical. It stood separate from mainstream wine. And it annoyed the heck out of many in the wine establishment — at least those who had stumbled across it. As its visibility rose, the annoyance levels did, too. This was chiefly because by co-opting the term ‘natural,’ this winegrower alliance seemed to be implying that all other wines were unnatural. It’s also because they represented a challenge to conventional wine education and training. Natural wine didn’t fit into the existing fine wine aesthetic, and there was a clash of cultures.

But, against all odds, natural wine gained traction. From its French base, the natural movement spread to Italy in the first instance, and then throughout Europe, to the U.S. and Australia. Georgia, a country that had an unbroken tradition of 8,000 years of making wines with no additions in large sunken clay vessels called qvevri, realized that these wines counted as natural, and they joined the party. Vocal champions emerged, most notably New York-based writer Alice Feiring, and French-born London-resident Master of Wine Isabelle Legeron. Both penned books, and Legeron was the organizing force behind the RAW WINE fairs.

While natural wine has grown as a movement — and still exists for some as an exclusive club of which to be a part — it has remained a small niche when the extent of global wine production is considered. But because it also emerged at a time when there have been changes in attitude in the mainstream wine industry, its real impact has been much larger.

In the vineyard, viticulturists are beginning to talk about the importance of soil health and what true sustainability means, and traditional herbicides are becoming socially unacceptable. While it used to be rare for wines to be fermented with wild yeast — allowing the microbes present on the grapes to carry out fermentation — this is now much more common. And conventional producers have been prompted to question their use of additives such as sulfur dioxide.

In fact, many aspects of winemaking that were championed by natural wine folk have now become much more common, even replacing some of the triumphs of more heavy-handed methods. As more producers trend away from making big, international-style reds with dark color, sweet fruit, high alcohol, and obvious new oak character, extracting less color and tannin for lighter-style reds is gaining popularity. In the Douro wine region of Portugal, for example, the leading table wine producer, Niepoort, has changed the style of its wines. Successful in the late 1990s, Niepoort’s once much more extracted and richer reds are now made from grapes picked earlier, with less extraction — and less winemaking generally — moving from small oak barrels to larger-format oak.

Also gaining in popularity is the use of concrete eggs and tanks, large foudres, and various clay vessels (amphorae, tinajas, talhas, and qvevri) for fermenting and maturing wines. In Spain’s Priorat DOQ, Terroir al Limit, one of its top producers, has moved to concrete only, getting rid of even large-format oak. And they infuse rather than punch down or pump over their red wine ferments, which are completely whole bunch. And while neither Niepoort nor Terroir al Limit are considered natural wine producers, their wines are better for these changes.

In Oregon, ceramics teacher and vigneron Andrew Beckham makes a range of amphorae for winemaking that he’s now selling on a commercial basis, to avoid the need for winemakers in North America to ship qvevri from Georgia (there’s a waiting list) or amphorae from Italy. In South Africa, an amphora producer named Yogi de Beer now has a full order book. And Sonoma Cast Stone, Nico Velo, and Nomblot all make concrete eggs and tanks that are commonly found in cellars worldwide. There’s also a “made in clay” festival in Portugal’s Alentejo each year, where the tradition of making wine in large clay talha is being revived. Alternative winemaking like this is now no longer solely the preserve of the natural wine ecosystem that made these vessels newly famous.

So as these methods become more widespread, where does natural wine finish and conventional wine start? These days, it’s hard to tell. Any sensible definition of natural wine — no additions except a bit of sulfur dioxide before bottling, using wild yeasts, organically farmed grapes — would actually apply to quite a lot of fine wines, many made by winegrowers who’d never claim to be making natural wine. And seeing the success of natural wine, where dedicated retail and on-trade channels have opened up a route to market for smaller producers, larger producers are sure to follow. Now that attempts are underway to provide a formal definition of just what constitutes natural, we can expect to see the big brands introduce “natural” sub-lines. In 2016, Romanian producer Cramele Recas surprised everyone by launching its “Orange Natural Wine,” a skin-contact white with no added sulfites. And while natural wines were previously only available at specialist shops and bars, they were selling in U.K. supermarkets for just £6 (roughly $8.50).

The result of all these changes is the blurring of lines between authentic, terroir-driven wine-growing and “natural” winemaking. And if the natural wine movement’s true purpose was to make the industry reconsider its position on issues ranging from farming to the need for additions and interventions in the winery, then its job is done. Natural wine fairs will continue, sure, but now that the practice is more mainstream, they will likely be a regular part of the wine ecosystem rather than just for those rebellious outsiders. The dedicated natural producers will still have their niche, but many working this way will simply sell their wines on the basis that they are really good drinks with a sense of place. They won’t need any badges: Their adoption of low-intervention winemaking is because they see this as a way to make more interesting wines. It is also a challenge that many winemakers enjoy: to work without a molecular safety net tests the skill of the vigneron. Good natural wine may occasionally be made by accident, but the top producers working in this genre know exactly what is going on: They might not intervene much, but they observe and monitor a lot.

So it can be argued the wine world is a better place for natural wine and all it’s brought to the table. But as natural wine’s practices and purported virtues continue to become more prevalent, it’s time for it to leave the stage, step back, and make way for the next movement to propel the wine industry forward.