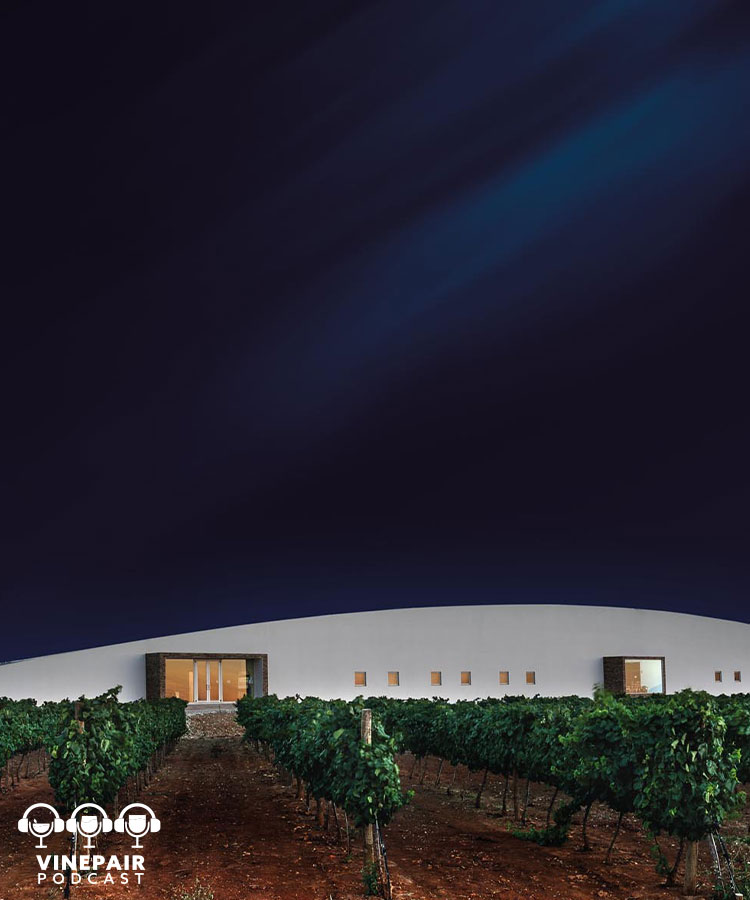

In this episode of the “VinePair Podcast,” host Zach Geballe speaks with Master Sommelier and president of Full-Circle Wine Solutions Evan Goldstein. The last time Goldstein appeared on the podcast, he talked about the many wines coming out of Alentejo.

Now, he’s back to teach listeners about the many sustainable practices taking place in the eastern region of Portugal. Through the Wines of Alentejo Sustainability Programme (WASP), strides are being made to combat the effects of climate change on grape vines, protect the region’s resources, and ensure that winemaking remains viable for the next generation.

Tune in to learn more about the wines and sustainability efforts of Alentejo.

Listen Online

Or Check Out the Conversation Here

Zach Geballe: In Seattle, Washington, I’m Zach Geballe, and this is the “VinePair Podcast.” Today, I’m joined by Master Sommelier Evan Goldstein, who’s the president of Full-Circle Wine Solutions. We are here to talk about a wine region that you’re passionate about, Evan, which is Alentejo. It’s a place that is definitely high on my list to visit in terms of wine regions in the world, but I have enjoyed the wines from there. Evan, thank you so much for your time.

Evan Goldstein: My pleasure. I’m happy to be here with you, Zach. I’m looking forward to chatting about all things Alentejo today with you.

Z: Excellent. I’ll remind listeners right at the top here, you and I and my co-host Adam Teeter chatted about the region in December of 2020. We’ll link to that in the show description. That’ll be a great reference if you want more of the nitty-gritty of the varieties and styles that define this region. We’ll give a little overview, of course, for those of you who either didn’t memorize that episode or don’t want to go back and listen to it. But we’ll focus a little more on some other topics for this conversation. With that being said, for those who aren’t familiar with Alentejo, where are we?

E: Alentejo sits in a fairly large chunk of Portugal. Portugal is the little piece of fruit that the larger Pac-Man called Spain surrounds on all sides. It’s literally got Spain to the north of it, water on the other parts, and Spain to the east of it as well. The Alentejo itself covers about a third of the country, located east and south of Lisbon and goes almost all the way down to the water. It’s big, but it’s also relatively sparse. It’s home to only about a tenth of the population. As we talk about topics like sustainability and climate change and all that other fun stuff later on, it’s important to note that it is sparsely populated. That said, it represents approximately 12 percent of all of the area under vine in the country, so it’s significant. And a little bit south of 20 percent of the entire wine production across the country, too. So it’s a very, very important wine region. It’s beautiful and home to lots of flora, fauna, and other types of wildlife that we don’t see in many other parts of the country.

Z: Gotcha. From a wine-centric perspective, what are we talking about? You give some numbers in terms of how it fits into Portugal’s broader production. But what kind of wines do we find from Alentejo in terms of styles, varieties, categories? However it makes sense to you to organize it, what would people tend to find either here in the States on the shelf or if they were to visit?

E: Good questions here. First and foremost, giving a little bit of insight into where we’re going, we’re definitely in the interior. So we’re not along the coast, either to the west or close to the water down to the south. It’s a very Mediterranean climate, it’s a very warm climate. If you’ve been there in the summer, you’ll know that it makes Las Vegas look like the Arctic. Because of that and because of wine-growing conditions, you can imagine it’s table wine-driven. They do produce small amounts of fortified wine, but it’s basically table wine-driven, very little bubbly, and red wine-driven because of these temperatures being what they are. Some of that temperature is mitigated by either a little bit of inflow from the ocean to the west that comes through the south and some by altitude. But other than that, it’s a lot of undulating hills and a lot of warmth. It’s about 80 percent red and the balance being white; there’s just a kiss of rosé. They are not really into rosé wines, which has always puzzled me there. Wine styles themselves are generally blends, which is to say you don’t see a lot of individual variety wine labels. Not to say that there aren’t some, but most of the wines are blends. Either originally, because of the way vineyards were planted, but also over time by style, what people like to make, what people produce, and what people like to drink. One of the things that folks don’t know oftentimes is that, if there was a People’s Choice Awards for Portuguese wine, Alentejo would win it. They represent almost 40 percent of all of the wines consumed within the country.

Z: Has that historically been the role of Alentejo as a wine-producing region? Has it mostly been domestic-focused in terms of its production?

E: Yeah, it really has been. If you go to restaurants throughout the country and you ask for the house red or the house white, even if you weren’t in Alentejo, there was a good shot that the wine that they would serve you would be from there. A lot of that is because it’s always been a workhorse of a region for the country, before it started moving towards a more premium direction in the last five to 10 years. But also, it produces a certain style of wine. The reds are scrumptious, full-bodied, rich, easygoing, not super hard, and delicious. And the whites are also texturally richer and fuller in flavor. Not necessarily with a lot of the hard, sharp edges that you would find in places like the Minho on the coast where you’re much closer to that to the water.

Z: Gotcha. Just because I enjoy hearing you say things in Portuguese and I can’t do it very well, what are some key varieties in the region?

E: The most important grape variety for white wines, which manages the hot temperatures but also maintains varietal character as well, is one called Antao Vaz. Antao Vaz was apparently a gentleman at some point in the time who was the source of the plant material that propagated throughout the region. There’s also an Arinto, you also see Alvarihno there. But Antão Vaz would really be the driver. Siria would be another great thing you would see. With most Alentejo white wines, they’re just going to be listed as “branco” or “white” because they are going to be blended. With the reds, you’re going to find grapes like Alicante Bouschet, which is a very thick, inky grape wine. You’re going to find Touriga Franca. You’ll find a little bit of Touriga Nacional. And once again, these are generally blended-style reds. Easygoing, but obviously the big dog there. If the wines are primarily Alicante Bouschet, they’re going to be inky, dark, and can be reasonably tannic.

Z: Before we start kind of talking more about sustainability and looking to the future and all those things, I wanted to ask a question that I don’t think we talked about last time we chatted. I talk to people about some wine regions in Europe about these wines that have been domestically focused, either because there wasn’t a broad international market for their wines until relatively recently, or things have changed in the region. People often come up and say, here are the classic dishes of, in this case, Alentejo or of Portugal more broadly. For wines like this, when we’re talking about enjoying them here in the United States where you and I are, what are some foods or dishes that you think pair well with some of these wines if they’re curious to check them out but don’t necessarily have a Portuguese cookbook lying around?

E: Right. Because there are so many Portuguese restaurants dotting the United States; it’s everywhere we go. The food of this region is, to me, the quintessential comfort food of Portugal. There are a lot of stews, there are a lot of rich braises, there are a lot of dishes that are both hearty and rich and comforting. Although it can be hotter than hell in the summer, it can be colder than cold in the winter, too. There’s not a lot of tweezers, there’s not a lot of fancy ingredients, there’s not a lot of Michelin chefs and stuff like that. Because of that, the foods of this region are beloved throughout the country. You’ll find Alentejano dishes served not only in that region, but around the country as well. What I like about that is, who doesn’t enjoy rich comfort food, be it a roast chicken or a pot of chili? I would think of that as being the kinds of foods one would find in Alentejo. These are the kinds of foods that, over time, what goes together, goes together. That can then be extrapolated into the kinds of foods I would enjoy with them here. So a lot of basic comfort food, whether it’s burgers and pizza to roast chicken or chili con carne to a braise of fishes. These are all going to go well with these wines. They don’t demand threading the needle, the complexity of layers or flavors to pair well with the idiosyncrasies of that cool-climate Pinot Noir that is as tight as a drum head in terms of the flavor profile. The wines here are approachable. They’re easy. The people of Alentejo are approachable and they’re easy. It’s not to say that they can’t stand next to a very rich and complexly assembled dish, but they certainly don’t demand it.

Z: Very cool. You said chili and that was the first thing that I was thinking about as a great fit for some of those warmer climates, full-bodied, but maybe not overly tannic reds. That is such a great pairing.

E: Anything that you can serve in one pot is going to be fine. Be it minestrone, chili, whatever you want to do, it’s all going to work well with these kinds of wines.

Z: Fantastic. We’ve talked about one of the most important climatic elements of Alentejo, and that’s the heat. So much of what we’re going to talk about for the rest of this podcast is going to be centered around this notion of the region. How the winemakers in the region are confronting, not just the heat that is a natural condition in the area, but the very real threat and challenges of climate change either intensifying or in some ways altering not just the total temperature, but maybe when heat comes and how long it stays and what else it comes with? For some of our listeners who might not be super well-versed in understanding what some of the challenges of viticulture in a really hot region are, maybe you can explain to listeners what it is about a really hot growing region that makes growing grapes challenging?

E: There are two things that are involved here. Number one is that the ample amounts of heat over time are not going to be particularly healthy for grape vines. Too much warmth towards the end of the season is going to shrivel up and dry your grapes and force one, if one is legally able to do so, to plump them up through irrigation, which changes flavor profile and balance. Over the course of the years, when vines are young, they can wither and sun can be very inhospitable to them. But usually hand in hand with ridiculous amounts of heat comes a lack of water, particularly in Mediterranean climates. A lot of people probably could surmise based on that picture that we’re painting for them, is this heat and lack of rainfall makes the area really vulnerable. It makes it vulnerable to not only grapes and a lot of crops being treated poorly, but also to people having to adjust their lifestyles to certain flora and fauna. Because if you don’t, they’ll go the way of the polar bear. But that’s cold, no pun intended. It can be a very, very challenging thing. On the bright side, having warmer, drier climates enables people to go more sustainable and organic. They don’t have to dispense as many pesticides and use as many treatments to do things that naturally happen in the vineyard because of the warmth and the lack of moisture.

Z: That’s a good point that while there are detriments, or at least challenges, with heat and dryness, there are obviously benefits. That lack of rot and pest pressure is certainly part of it. To this question of water and the challenges of it, I’ve often thought that there is something that doesn’t get talked about enough in sustainability conversations is, people often talk about, at a certain superficial level, how grape vines don’t require as much water as many other crops. And I think that’s undeniably true. There are certainly many more water-intensive crops, but one of the other things that’s true is that grape growing and winemaking in certain places and in certain ways can still be very water-intensive. Until relatively recently around the world, growers might be careful, if they’re in a place where they are allowed to irrigate, about how much water they apply to their vines, but that might be profligate with water in other ways. One thing that’s really interesting to me, and we can use this as a springboard to talk about the Wines of Alentejo Sustainability Programme, is how much it seems like there’s emphasis on not just some of the elements of sustainability like organic viticulture that tend to spring to mind, but some mundane but important things like recapturing wastewater.

E: Absolutely, I think you’re right. Most people with a very broad, inaccurate brush like to think of, “What am I doing in the vineyard?” and “How much compost should I use?” when they think about sustainability. When it all goes down, we sit and talk about how oil is the big thing and all of that. It all comes down to water in the end. Doing things such as installing water meters, encouraging lower water consumption, and giving people goals like we’re used to in California where I live, where they tell you to voluntarily conserve 10 to 15 percent of water. That’s something that they’ve been doing for a while. It was not always the case in Alentejo. So they’re encouraging people to do that. Over 60 percent of the members of the organization that we’ll talk about later now do that significantly. And that has really dropped their water. I get questions about it. How do you increase recycling? How do you convert organic wastewater and reuse it again? How do you encourage people not only to think about this in their day-to-day agriculture, but then take it home, adding in the human component to it so that you’re practicing safe and regenerative water policies in the confines of your home, not just at work?

Z: Sure. You made a really good point there, which is that, it’s all well and good for a region or a body to say, “Here’s what our goals are,” but uptake is really the most important thing. Goals are great. But if wineries, growers, etc., aren’t working to achieve them, it can be empty. And I would love for you to talk a little bit about the Wines of Alentejo Sustainability Programme and how, to me at least, it does not seem to be an empty signifier.

E: That’s a great point. Wines of Alentejo Sustainability Programme goes by the acronym of WASP. I don’t know whether I like it or not, I don’t know if wasps are good for sustainability or not. It seems to me they probably don’t sound like they are, but nevertheless, it’s a nice acronym. It was launched in 2015, and it’s a voluntary membership program. People don’t have to be there. They use ample amounts of data that they’re able to help look at creating best practices in sustainability programs. First of all, they didn’t just pull this out of a proverbial Cracker Jack box or the Portuguese equivalent thereof, but they took a look at who was doing it well. If you look at North Stars in sustainability around the world, the two that really come to mind for me are Chile, who has certainly been doing it for a long time, and California. If you look at a microcosm of, for example, the Lodi Rules program, they’re up there at the top of Napa and Sonoma and all the other counties that do a tremendous job, too. After doing a lot of research and pulling together a lot of the data and coordinating this with the producers but also the university in Evora, they put together this organization and all these various tenets of following to make this happen. They felt very strongly that not only embracing sustainability was important and everybody’s doing it these days, but it’s a necessity for them. They can’t go on doing things the way we’ve been doing, or are going to go the wrong way. So they really started hard. They had 96 members of vineyards and wineries by the end of the first year. Today, they’ve got well-over 400. I think the number is 430 right now, representing wineries and wine growers there. If you add those up, it covers more than 50 percent of all of the vineyard land. All the main players in the country have engaged in the program, and it’s been an undeniable success.

Z: I want to throw out a theory that I’m curious if you might agree with or potentially disagree with. Either way makes for compelling listening, I think. It struck me when I was planning for this episode that places like Alentejo, and to some extent Chile and California as you mentioned, are at the forefront of the sustainability movement. As you said, especially in Alentejo, it’s out of necessity. Necessity is always going to be a very powerful motivating force. I was wondering if in some ways, we’ll see something like what we saw in some other elements of grape growing and winemaking, where a lot of developments in the ‘80s and ‘90s out of Australia managed a really limited labor force and had to learn more about mechanization in a way that could still allow for producing really high-quality wines. Dealing with some of the viticultural and winemaking practices and climatic challenges that are similar, but also somewhat different, in Australia. Now, we’re even getting some of our most advanced research on things like fire damage and smoke taint that comes out of Australia, because they’ve been dealing with it longer. Does that sound like a reasonable parallel, or am I out on a limb here?

E: No, no, I think I think you’re spot on. We pointed out a few things at the outset of our conversation that this is an area that has got lots of land, but not very many people there. So they have become increasingly dependent on some forms of mechanization. It could be as geeky, if you will, as using sprayers when you have to spray sulfur. Things that have drift recover technology to capture and recycle that spray drift, again in that whole sustainability thing. Or reducing water consumption not only by actually having to do it, but also dry cleaning equipment technology, which means that you don’t actually have to use water to do some of those things. Those are people-dependent; they are also resource-dependent. And the fact that large distances between areas and large vineyards don’t necessarily have the same labor-to-vineyard size there allows the equivalent of Juan Valdez to go there in manicure and pick each grape individually when it’s ripe. You are going out there with some mechanization and a more industrial approach. It’s a bigger area; it produces a lot of wine.

Z: We talked about labor a little bit in terms of the challenges that come from having a broad geographic region without a huge population. We’ve talked a little bit about tourism, water, and other things. But what about energy, along with this thought that water will continue to be a persistent challenge? With energy usage or just limiting how energy intensive or even potentially looking at energy regeneration in various ways, what is going on in Alentejo in terms of that?

E: Great point to bring up. Things that seem relatively commonplace where you go, “Oh my God, I can’t believe people weren’t doing that” have become more normal. It might go without saying to you and me that installation of your pipes or installation of your tanks or using LED lighting and installing beaucoup solar panels because you have so much sunlight would be normal, and it is becoming that way. Obviously, if you’re starting from a relatively low base to bring it up quickly, the numbers are extraordinary. But it wasn’t, once again, always done that way. So I think there is incredible sensitivity towards reducing energy consumption. I don’t have the data to talk about regenerative energies, if you will. But reducing energy is something that’s very much top of mind for people. As well as greening, recycling, and all these other things. But the point you brought up that I do think is worth bringing up again, is the so-called “human component” of what sustainability is all about. One of the things that you could probably imagine is that if you’re in a part of the world where people are sparse and scarce, you risk brain drain, and you risk migration to the cities where the jobs are. So you really need to think about, “How do I maintain the sustainability of the population and the labor force here?” They do things through this WASP program that I think are outstanding, such as assisting and creating school programming for the children of the people that are there, if you’re out working in the vineyards or working in the wineries and you don’t have support at home to pick up and get your kids off to where they need to be for school or support them. Or in firefighting, a lot of these people have volunteer fire and emergency services donating through proceeds that are pulled from the WASP program to charity events. Also, just giving back to the community and making sure that people value and show great pride in wine as a significant product of the community, along with cork and olive oils and things like that, so that families are encouraged to take pride and literally encourage future generations to enjoy and take pride in their local wineries.

Z: That was a really important point that I was going to mention, too. In some cases, there might be financial incentive for doing this, whether it’s to save money upfront or to recognize the potential value proposition, either now or in the future for wines that are truly sustainable. They may have a marketplace advantage. But also, for a lot of places in the world these days and now — and Alentejo is no different — there’s a tremendous pride in the wine industry. But also, there’s the recognition that pride alone will not keep it viable.

E: Absolutely. When I was down in Argentina years ago, I was talking with a couple of producers down there who created working daycare centers on the property at the winery, where the people who worked with them in the vineyard could drop their kids during the day. They could create this sustainable human ecosystem and enjoy their work and take pride in their work, and know that work had their back in a way that another industry that’s a bit more cutthroat wouldn’t.

Z: Very good point. The last thing I wanted to chat about is this idea of the portability or the exporting of the wines, but also this emphasis on sustainability. So much of the conversation that’s happening in the world, and in our little corner of wine, is about these forward-looking programs and understanding the importance of sustainability. Sometimes, I hear from producers or regions that they don’t know where to start. It can feel like such a big topic. One thing that’s really cool about WASP and what’s been done is, it’s only seven years old. And yet, it seems to have had a lot of uptake. It has had a lot of success. Are you seeing interest from other parts of the world like, “Let’s look at what they’re doing in Alentejo.” Every last piece of it can’t be transported to our region for whatever set of reasons: different climate, different culture, etc. But there are pieces of this that we can very much learn from.

E: Oh, absolutely. What’s that old expression? “Great ideas don’t care who had them.” If somebody is doing something good, we should all benefit from it. Just as a quick aside, and then I’ll jump right back into this. Oftentimes, it takes a single region to lead a nation. I remember being in Australia, to use your point from earlier, and spending some time in McLaren Vale. McLaren Vale has led the sustainability, biodynamic, and all of those things for that entire country in the same way that Alentejo has been doing it, not only for Portugal, but for Europe in terms of leading by example, having protagonists within the organization that live and breathe the philosophies and holistic tenets of what’s going on there. To your point, I think that WASP has now become a model for others in the sense that the network they’re making is not only important to Portugal. For example, they were one of 15 winners out of 200 applications for the European Commission’s European Rural Innovation Award just a few years ago. In 2020, they went on to get even more of that for the Rural Innovation Ambassadors Program and national recognition and all of that. I do think that they have been an absolute leader within Portugal, but also in Europe to the point where they’re now partnering up with various other certifying bodies around Europe and helping work together collectively. They are doing some work right now, I believe, with some consortia in Italy to share findings and technology. Because we all win when best practices are shared across borders.

Z: Excellent. Evan, this has been really interesting. It’s all the more reason to be interested in not just enjoying the wines of Alentejo — although that’s a good starting point — but eventually visiting the region and hopefully not frying or freezing. Maybe I’ll pick a shoulder season. I can always sit in the shade.

E: Absolutely. The cork trees are good for that. Just one last thing as we close — there’s a topic that I thought would be important. We don’t talk about this enough, but if you talk about cork, you talk about Portugal. If you talk about cork and Portugal, you talk about Alentejo, where the lion’s share of cork trees are actually planted. What people don’t think about there is that cork trees, without question, are the most carbon-retaining tree of any kind in the country. They literally pick up three to five times more CO2 out of the air than any other bark there. Ten million tons of carbon dioxide are sequestered by cork trees in Portugal annually, which, in the grand scheme of sustainability and climate change, is really important.

Z: Yeah, absolutely. This was a really interesting and important conversation. I look forward to seeing what further developments and best practices emerge from Alentejo and enjoying the wines in the meantime.

E: The pleasure is all mine. Thank you so much for having me on the show, and I wish everybody out there good drinking in 2022.

Thanks so much for listening to the “VinePair Podcast.” If you love this show as much as we love making it, please leave us a rating or review on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever it is you get your podcasts. It really helps everyone else discover the show.

Now for the credits. VinePair is produced and recorded in New York City and Seattle, Washington, by myself and Zach Geballe, who does all the editing and loves to get the credit. Also, I would love to give a special shout-out to my VinePair co-founder, Josh Malin, for helping make all of this possible, and also to Keith Beavers, VinePair’s tastings director, who is additionally a producer on the show. I also want to, of course, thank every other member of the VinePair team, who are instrumental in all of the ideas that go into making the show every week. Thanks so much for listening, and we’ll see you again.

Ed. note: This episode has been edited for length and clarity.