The first sake I ever had was in a Japanese restaurant in Maine. It was served warm and was unlike anything I’d had before – not really beer, not really wine – but so complementary to the rice and fish it accompanied. Outside major cities, the sake selection at most restaurants is limited to bottles that are easy to find and often low quality. It wasn’t until moving to New York City and getting to know the sake bars of the East Village that I learned just how diverse – and confusing – a sake menu can be.

Today, I consider sake one of my favorite things to drink with food and would go out on a limb and say that with the vast number of flavor profiles and textures, the right sake pairing could be just as good as wine. But it’s not uncommon for sake lists to have dozens of bottles to choose from, and they often include only the information about the prefecture and type. On many lists, the only words written in English are the sakes’ translated names, plus some evocative but uninformative descriptions like “Eternal Embers” or “Dreamy Clouds.” Fortunately, you can learn a lot about a sake list with a short vocabulary lesson.

Let’s start with how it’s made. Sake is made out of rice. As with wine made from grapes, the ABV is typically about 13 to 15 percent. And like wine made from grapes, there is a huge range of quality in sake production. The price and complexity of a bottle can be affected by the quality of the rice, the softness of the water, and aging practices. The most important step is the milling of the rice. Generally, the more of the outer layer that’s buffed away, the more aromatics will come through in the final product. Japan takes this very seriously by enforcing strict rules on what terms can and cannot be printed on a label and on a menu, which is great for the consumer.

Most sake lists are broken down into the following categories: Junmai, Ginjo, Daiginjo, Honjozo, Nama, Nigori, or Tokubetsu. Like “white,” “rosé,” or “sparkling” on a wine list, these titles will give you an idea of what flavor profile to expect. Knowing the differences is your first step to understanding a sake list.

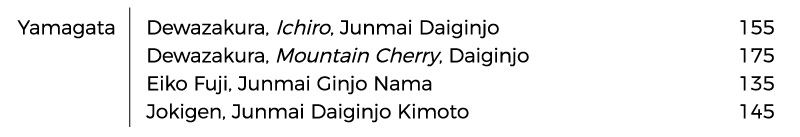

Here is an example of a classic sake listing, from Sushi Nakazawa, NYC, which boasts one of the more impressive lists in the city:

As with a wine menu, each word means something different, unique, and specific about how the sake is made and how the final product turns out. The first words listed (Dewazakura, Eiko Fuji, and Jokigen) are the producers. These are followed by the titles – in italics – and then the style of sake.

Let’s take the first one. Yamagata is the prefecture or area. Each region grows different kinds of rice based on their differing climates. Then you get notes on the style.

Here’s a breakdown of common styles:

Junmai

Junmai means your sake contains simply rice, water, koji mold, and yeast. It is the purest expression of sake but it has no milling requirements, so it can be relatively rustic.

Honjozo

Honjozos have a bit of brewers alcohol added to them, usually a very small amount. This is not an indication that the sake is of lesser quality, or that it’s especially boozy or sweet. This is an ancient practice started by producers who noticed that some of the delicate flavors can be highlighted when adding a bit of neutral alcohol to the fermented batch. Honjozos are a bit lighter and perhaps less complex than their rustic, Junmai sisters.

Ginjo

Gin means “careful selection,” and Jo means “ferment” in Japanese. Ginjo denotes a carefully selected brew. Ginjos require a higher amount of milling, which means higher costs and a better quality. If a label says only “Ginjo” it is safe to assume is it also a Honjozo style. Otherwise, it will say “Junmai Ginjo”

Daiginjo

Dai means “Great” so Daiginjo literally means “Great Ginjo.” This style has an even higher milling requirement — sometimes 77 percent of the rice is buffed away! Again, if the menu says only “Daiginjo” it is safe to assume it is Honjozo style. Otherwise, it would say “Junmai Daiginjo.” Junmai Daiginjos are thought to be the highest quality sakes and the best with food. They will therefore almost always cost you the most money.

Here are a few other words that may help guide you:

Genshu

Sake must be diluted to achieve the desired alcohol content, but Genshu is sake that is bottled without dilution. Alcohol can range from 16 to 22 percent.

Kimoto or Yamahai

These are sakes that have lactic bacteria blended in, so the final product tends to be funky with a creamy texture.

Koshu / O-Ko Shu / Ko-Ko-Shu

This is aged sake, which generally has more oxidative or earthy notes (just like an aged wine!).

Namazake (or Nama)

This sake is unpasteurized and must be refrigerated! These are very fragile and break down easily but can be spectacular. Make sure you’re at a reputable establishment and trust that they’re taking good care of their sakes.

Nigori

This is unfiltered sake. There’s usually some lees and rice particles left from fermentation, so it’s almost like drinking a wheat beer – it’s thick, cloudy, and creamy. Some people choose to shake the sake to emulsify the solids, while others choose to pour off the clear liquid, leaving the solids on the bottom. Some sake connoisseurs look down on Nigori because it’s not the most pure expression of the rice, but I find this expression to be a delicious crowd-pleaser. It’s sweeter, with a soft, silky texture.

Taruzake

This is sake that has been aged in cypress or other new-wood casks, rather than a neutral vessel. If you like a more robust flavor, you’d be happy with this selection.

Shizuku

Shizuku means “free run.” It means that with this sake, at the end of fermentation, rather than being pressed to separate the liquid from the solid, Shizuku is hung in bags and the liquid runs out with no other manipulation than gravity. As you can imagine, these get pricey. If you see a “Junmai Daiginjo ‘Shizuku’” on a list, go for it! It’ll be delicious and worth every penny.

In the case of the Jokigen sake on the list pictured above, you can expect that a Junmai Ginjo Kimoto is a high-quality brew with no added alcohol with lactic bacteria blended in. The final product will be soft on the palate and funky from the lactic bacteria but a bit more rustic without the addition of alcohol to bring out the aromatics.

Challenge yourself!

How would you guess the following styles to taste? What would you expect to spend?

- Junmai Ginjo Koshu

- Junmai Daiginjo Shizuku

- Yamahai Daiginjo

- Yamahai Junmai Koshu

- Junmai Daiginjo Nama Genshu