Scott Dorsch was in a bind. The agronomist for Colorado’s Odell Brewing had begun working on a new double IPA with the brewing team and they were confident that they’d found the hero hop for the recipe. Created by the Hop Breeding Company, a partnership between Yakima Chief Ranches and John I. Hass, the variety is currently known as HBC 586. Dorsch praises its citrus and stone fruit character and describes this experimental hop as well adapted.

“I’m pretty sure we came across 586 when it was a single hill,” he says. “We were like, ‘whoa.’ It was like eyes meeting across a room — love at first sight.”

Odell went on to sponsor 586, financially backing the cultivation of a sufficient volume to be able to brew with it on a commercial scale. As such, the company was promised a significant percentage of the 10-acre harvest, much of which was earmarked for the double IPA to be named Hammer Chain. The problem, if you could call it that, was that Haas also recognized the potential in this experimental hop and wanted more brewers to be able to get their hands on this exciting new varietal. Haas wanted a larger share of the harvest.

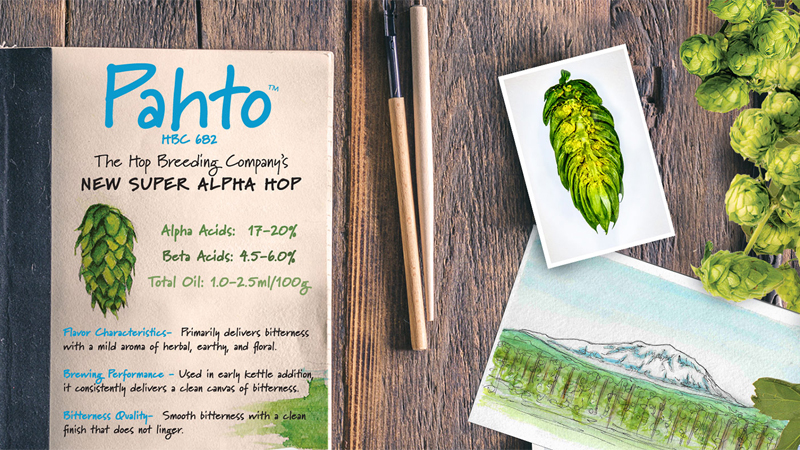

With decades of combined breeding experience between them, Haas and Yakima Chief, not to mention other public and private breeders, are getting better at knowing when they have a hit. Citra, the hop that turns up in nearly every other beer these days, also came from the Hop Breeding Company. Before its release in 2007, those in the industry knew it as HBC 394. Two years after it was introduced commercially, growers harvested 98 acres of Citra in Washington State. By 2019, that number had increased to 6,720 acres, with another 1,971 in Idaho and Oregon. If 586 becomes another Citra, that’s big business.

In today’s brewing landscape, hops are the star ingredient, perhaps more so than ever before. Over the past decade, hardly a year has passed without news of one or more new strains reaching the market. Packed with flavor and aroma compounds that run the gamut from blueberry to tangerine and coconut to watermelon, these precious plants have brewers jockeying to be the first to trial an experimental variety while savvy consumers eagerly scan product descriptions for mention of a current favorite. As Thomas Nielsen, raw materials manager at Sierra Nevada Brewing and president elect of the Hop Research Council says: “It is truly all about the hops. Don’t let anyone ever tell you anything else.”

What beer fans and professional brewers won’t necessarily tell you when the subject of hops comes up is just how difficult it is to develop each and every new variety. As one breeder put it, the stars have to align. On average, it takes about 10 years to bring a new cross — the child of two interbred plants chosen for their desirable properties — to market. And this requires the expertise of many people, from hop breeders, to farmers, to lab technicians, brewers, and consumers, too.

“It does take a village,” says Shaun Townsend of Oregon State University. “And it takes a long time to vet out the genotypes.” An associate professor at OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences, Townsend has spent his career studying plant breeding and genetics and since 2010, has led the school’s aroma hop breeding program, which is supported by Oregon-based merchant Indie Hops. As he describes it, research and development is a three-phase process: experimental trial, advanced trial, and, finally, commercial trial.

During the first phase, Townsend’s goal is to identify female hops (male and female plants are separate and males don’t produce the resinous cones used in brewing) that will be agronomically suitable. In short, he’s selecting for overall health. After choosing the various parents he wants to work with, he’ll cross-pollinate them and let the seedlings grow in a greenhouse, paying close attention to disease resistance. From there, the young hops move to a field, where each potential variety is planted in a single small hill and again evaluated for resistance to disease and pests. Since hops aren’t fully mature until the third growing season, Townsend usually waits until this point to evaluate yield, cone architecture, chemistry, and desirable sensory characteristics.

Ultimately, crop production matters more than tantalizing aromas and novel flavor combinations. It’s a fact that’s tough for some beer makers to accept. “Even though we’re brewers, we have to be mindful of agronomics,” explains Christian Holbrook, brewmaster at New Belgium Brewing.

According to Holbrook, yield is a particularly important metric to New Belgium, in part because it relates to sustainability, a core value for this Certified B Corporation. In Washington’s Yakima Valley, the country’s largest single hop-growing region, an acre of land typically produces an average of 2,000 pounds of hops each year. Holbrook says New Belgium has sponsored another Hop Breeding Company experimental that has yielded 2,800 and even 3,000 pounds per acre. Known as HBC 522, it appears in Voodoo Ranger American Haze as well as Voodoo Ranger IPA. He describes it as more of a workhorse than a superstar, but praises its ability to yield more than older varieties like Cascade, Centennial, and Willamette. It also outperforms Citra, which usually produces closer to 1,600 pounds per acre.

“The harvest window is also kind of nice,” Holbrook adds. “This is a really late-ripening variety — as late as October.”

Once a new genotype graduates or progresses from the first phase of development, hop breeders like Townsend establish testing nurseries to see how the plants fare under different growing conditions. OSU’s program works with two farmers in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, one on the east side and another on the west side. At each location, he might have as many as 30 genotypes at this advanced trial stage, and about 20 plants per genotype. During these fourth, fifth, and sixth years of the process, the farmers manage multi-hill plantings of each trial variety, while Townsend and his team walk the field to collect data, and at the end of the growing season, harvest the hops. The genotypes with real promise are beginning to emerge at this point, and by the fifth year or so, a small handful have desirable characteristics. “I get a good read on the potential yield and we can now do some small-scale pilot brewing,” Townsend says. “[That’s when] we gain valuable feedback from brewers on how that hop may play.”

The challenge throughout this process is that it’s difficult to predict what exactly an experimental hop will impart to a beer before brewing with it. Not to mention the fact that consumer preferences change faster than a hop can get to market. Breeders can’t necessarily target a set of aromas and flavors in advance. So while rubbing hops in the field is still the first chance for brewers to preview a new variety, and sharing information about alpha and beta acids and total oil content is still useful to a certain extent, any hop that has a chance of becoming the next superstar has to impress our senses in a glass.

“In the end, it can smell great in the field, but if it doesn’t come through in the beer, that’s a problem,” says Jeremy Moynier, senior manager of brewing and innovation at San Diego’s Stone Brewing. “With Cashmere (a public variety that debuted in 2013 and appears in Stone’s new low-calorie Features & Benefits IPA), what you’re smelling really does translate. But sometimes you’re like, ‘What happened?’”

With up to 10 pounds or so from an advanced trial variety, brewers like Dorsch, Holbrook, and Moynier have enough to brew a single-hop pale ale or IPA on a pilot system. When possible, a brewer might try to revisit an appealing variety over multiple seasons to better understand its character. Not only does this allow them to put the beer through a sensory panel and learn how a hop performs with their house yeast, it also provides the brewery with its first opportunity to gather consumer feedback. Taproom exclusives are fun for fans, and they’re instructive for brewers, too.

“The nice thing about the Denver pilot [system] is that it has a hopback, so we can get a look at raw hops and pellets,” says Holbrook. “If we make a single-hop IPA that’s pretty aggressively hopped, and we get some good sensory feedback, that’s a good indication [that we have something].”

At this point, an interested brewery could decide to sponsor a new genotype, sharing the risk of planting up to 10 acres of hops. Odell has sponsored a couple of varieties over the years (HBC 638 and HBC 586) and has contracted for others at the advanced stage (Cashmere, HBC 472, Sabro, Strata), particularly since introducing Wolf Picker in 2014, an annually released pale ale that has since evolved into an IPA brewed with one or more experimental hops. Roughly six or seven years have passed since a hop breeder first planted seeds in a greenhouse, and the variety has now reached the third step of development, the commercial trial phase. Very few hops make it to this stage, but those that do have a real shot at getting a name and showing up in a beer bound for distribution.

“Mountain Standard IPA [a year-round brand that debuted in 2019] was designed around what we learned with Wolf Picker,” explains Dorsch. “I see 586 potentially finding its way into that beer. It’s a very complex hop that works well with our yeast.”

Odell’s so-called “mountain-style IPA” is built around Strata, Sabro, and Cashmere, a trio of newer varieties with the wow factor that causes brewers like Dorsch to fall head over heels. Slightly hazy, low in bitterness, and triple dry hopped to maximize fruity flavors and aromas, it’s also the very type of beer that drinkers have been enthusiastically supporting with their dollars — a fact that has led to more acreage for all three. Farmers harvested almost twice as many acres of Strata in 2020 as they did the previous year, while Sabro was up 68 percent over the 2019 harvest, and Cashmere acreage increased by 85 percent. In other words, don’t be surprised to see these names on the label of an IPA coming soon to a bottle shop near you.

“Sabro, you have to be careful with that one,” Dorsch says. “It can overwhelm other hops. [Cashmere] is a beautiful hop, I get a lot of white grape. It’s not a citrus bomb. We use it as a layering hop to balance the citrus. Much like Cashmere, OSU 331 [Strata] stood out from the pack and was a customer and employee favorite. The strategy is to blend them so the customer doesn’t notice.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!