You might have heard of claret, the catch-all, English-gentleman’s name for the red wines of Bordeaux. Nowadays, the word evokes images of an “I say there, old chap” class of power-lunch-eating, expense-account-drinking Oxford graduates.

But claret wasn’t always the preserve of the rich and privileged. The word is an anglicization of “clairet,” which was cheaply made, dusty-rose-colored swill that France began exporting to the thirsty English masses during the medieval period.

How did poor man’s clairet evolve into the majestic red blends of Bordeaux that posh, clubby types now call claret? It’s complicated. The story encompasses international warfare, epic ego, and the surprisingly ancient art of influencer marketing.

Call it what you like: Claret (née clairet) changed how we drink and talk about wines in Bordeaux and beyond.

*

Bordeaux and England share an intricate, often turbulent history.

In May 1152, Henry Plantagenet, the future King Henry II of England, married Eleanor of Aquitaine. An independent dukedom, which included the city of Bordeaux and surrounding wine region, Aquitaine became part of England.

At this time, clairet was the common style of wine in Bordeaux. Made using shorter periods of fermentation than are nowadays common, clairet lacked the intensity of color and flavor of modern-day reds. It was poor quality and turned sour within a few months of fermentation.

But clairet was cheap, and English drinkers became hooked. Aided by beneficial tariffs granted to the city’s winemakers, exports boomed. “By the 14th century,” eminent British wine writer Oz Clarke notes in “The History of Wine in 100 Bottles,” “some estimates reckon Bordeaux was sending Britain enough wine for every man, woman and child to have six bottles each.”

Seeing how prosperous Bordeaux had become, the French sought to gain control of Aquitaine, and, in 1337, the Hundred Years’ War began. (Fun trivia fact: The term Hundred Years’ War is actually a misnomer, as the war didn’t end until 1453 — 116 years later).

France (eventually) emerged victorious, and the flow of clairet to the British Isles ran dry. Bordelais wine merchants turned to the Netherlands to push their product, while the English quenched their thirst with wines from the Iberian Peninsula.

France and England remained in a state of on-and-off war for the next 400 years, but, by the 16th century, clairet regained prominence. English demand for the wine could apparently transcend the nations’ bitter relations.

During this period, winemaking was focused in regions to the south of the city, like Graves. North of Bordeaux city, where some of the most famous appellations are found today, was a barren marshland.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Dutch engineers drained the swamps north of the city. The region’s gravel-based soils turned out to be ideal for growing quality grapes, and Médoc winemaking was born.

The quality of the wine benefited enormously and was further improved by new vinification techniques and the introduction of new oak barrels. New French Claret, as it came to be known, was deeper in color than traditional clairet, more flavorful, and could age.

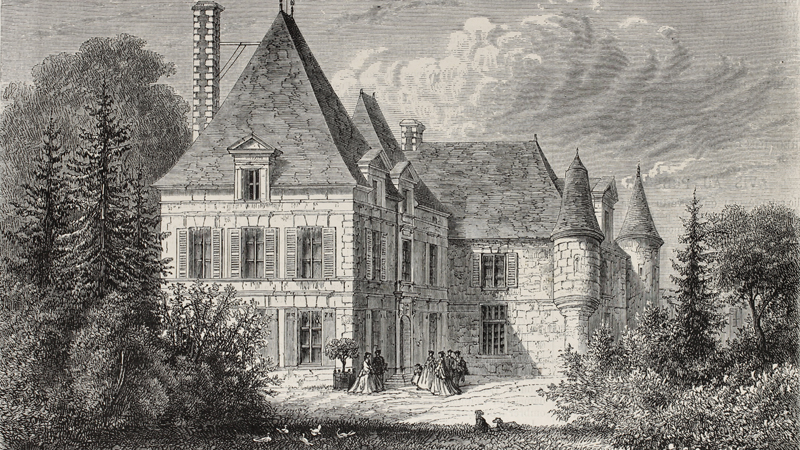

In Graves, though gravel-rich soils also abound, winemakers still favored the cheap, poor-quality clairet. All except for one, that is. Arnaud de Pontac, owner of the now world-famous Château Haut-Brion, realized that there was much more money to be made from the higher-quality New French Claret, and Haut-Brion became one of the pioneers of the style.

Back in England, Samuel Pepys, a keen clairet drinker and administrator in the navy, was busy documenting 17th-century life. His diary, which is now housed in Magdalene College in Cambridge University, offers an unrivaled insight on the introduction of New French Claret.

On April 10, 1663, Pepys wrote of a visit to the Royall Oak Tavern, where he sampled “a sort of French wine, called Ho Bryan, that hath a good and most particular taste that I never met with.” The wine was none other than Château Haut-Brion, and it cost him more than three times the amount of a normal jug of clairet.

The fact that Pepys was able to write the name of the Château where the wine was made — albeit incorrectly— was just as peculiar as the flavor of this new wine.

Traditionally, Bordeaux wines were purchased in bulk by city merchants, who blended them before shipping them off in casks. The names that appeared on these casks were not of the winemaking property, but of the Bordeaux merchants or the importer.

This practice didn’t sit well with the proud de Pontac, who believed his wine to be of superior quality. In a stroke of forward-thinking marketing nous, he hiked his prices so that wine merchants would be reluctant to blend his wine with their cheaper inventory. The Château Haut-Brion name remained.

By the end of the 17th century, French wine faced heavy customs duties in England — the result of more bitter relations and war. The quality of New French Claret, therefore, had to be high to justify this added tax.

New French Claret quickly became a luxury product, affordable only to the aristocracy. Just like Haut- Brion, the names of eminent châteaux like Latour, Lafite, and Margaux soon became recognizable status symbols, associated with the superior wealth required to drink their wines.

The transformation of poor man’s clairet to the English old boys’ tipple was complete.

Over time, the New French Claret style was adopted by almost all the winemakers in the region. In England, the name claret eventually came to be used for all Bordeaux red wine. But given its popularity among a certain social class, its modern day use still implies a more expensive and exclusive wine.

Confused? You’re not alone. To this day, even the English are unsure of exactly what claret refers to. The confusion is summed up perfectly in a sketch in the popular British sitcom “Fawlty Towers.” The show’s protagonist, Basil Fawlty, is a snobbish, socially ignorant hotel owner who dreams of becoming a member of more “respectable” social circles.

When wine connoisseur Mr. Walt visits his hotel, Fawlty tries to play up his knowledge of fine wine, stating that, unlike Walt, most of his guests “don’t know a Bordeaux from a claret.” Fawlty is then mortified to learn from his guest that “a Bordeaux is a claret.”