Rarely have bar fights made history. And in the case of the so-called “Battle of Brisbane,” it almost didn’t.

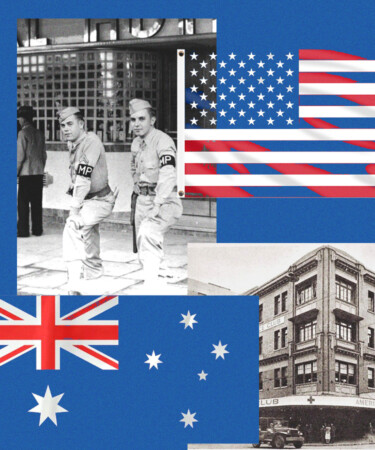

It was the end of November 1942, not yet a full year since the attack on Pearl Harbor. World War II was waging on, and General Douglas MacArthur had stationed some 40,000 American troops in Brisbane, Australia, after the fall of the Philippines to prepare for battle against Japanese forces in the Pacific theater. These U.S. soldiers were to bring much-needed manpower to the nation, which had a smaller population that could join the fight. Brisbane, a city of around 350,000, was on high alert for fear of invasion, and became one of four allied headquarters along with Honolulu, Washington D.C., and London.

Despite an early warm welcome from the Australian community upon the Americans’ arrival in 1941, skirmishes between the groups of soldiers weren’t uncommon, according to Robert Macklin’s book “The Battle of Brisbane.” Tensions had been brewing between the factions for some time, and the Americans’ higher pay was one major factor: Australian troops, many of whom had signed up for service in an effort to receive food and money during the Great Depression, had even rioted the year prior because of this discrepancy. Another point of contention? Americans were able to drink at the Australian Army’s canteens in Brisbane, whereas the Australians weren’t welcome in the American watering holes in town.

Though alcohol was being rationed, many overeager drinkers from both camps had more than their fair share of XXXX, the popular Queensland beer. Officers could hang out at the more upscale bars of Queen Street like Lennon’s, which was popular with war correspondents and — perhaps most importantly to the soldiers of all ranks — women. The Australian women’s sudden interest in the American soldiers thus became another source of conflict, even resulting in propaganda fliers with the “yanks” described as “over paid, over sexed, and over here.”

According to reports, the wild bar fight began on the evening of Thanksgiving 1942, when an American soldier was suspected of being off base without a pass at an Australian canteen. An American officer went to arrest him when more Australian soldiers came to his defense. Within an hour, the situation rapidly escalated, with crowds of fighting soldiers growing to the thousands. One soldier tried to break up the swarm of people, but when Australian soldiers caught hold of him, his gun went off, killing an Australian soldier named Edward S. Webster. Eyewitness accounts describe the chaos that unfolded around Adelaide and Creek Streets as both groups of soldiers damaged the bars of Brisbane with bricks and rocks, including the U.S. military’s Post Exchange. The American Red Cross Services Club across the street, which had opened earlier that day, was unaffected perhaps because it didn’t sell alcohol or cigarettes.

Despite a lull in the action overnight, the fighting continued the next evening as Australians trolled the streets searching for Americans to fight. The blackout restrictions that kept the streetlights off to save energy were temporarily lifted to prevent total anarchy. The “battle” finally ended around midnight as commanders got their ranks under control and crowds finally dispersed. But what remained was boarded-up windows at the canteens and a busy night at the local hospitals. Some of the men were even subject to court martial for their actions.

Despite other riots that occurred between troops in Australia, the battle was over in Brisbane. By mid-1943, the threat of Japanese invasion of Australia no longer seemed like a probability and in 1944, MacArthur returned to the Philippines. Not long after, victory was declared in the Pacific. That success is one reason the bar fight has been written about so little: The conflict was censored by both governments at the time in an effort to show unity in the war effort. An Australian military report cited in Macklin’s book said of the event: “It is of the utmost importance that every step should be taken to combat the spread of ill-feeling between the men of the two armies and to prevent a recurrence of incidents which, if unchecked, may have a serious effect upon our combined war effort.” While it’s been covered in Australian publications, it’s rarely mentioned stateside — and if it wasn’t for a Freedom of Information Act request in 2013, we might not know anything at all. There’s little evidence in modern-day Brisbane, either: The Lennons Hotel was demolished in 1972, and the sites of the remaining canteens where the soldiers imbibed before the skirmishes have since become banks and office buildings.

While this two-day brawl was impacted by cultural differences, pay, and a hearty dose of male bravado, the so-called “Battle of Brisbane” probably wouldn’t have happened without copious amounts of alcohol.