Unlike the kind of ugliness you’d see outside a beer-and-shot kind of dive bar (think “Roadhouse”), things are usually pretty chill in movies where Champagne is consumed. Folks are laughing, maybe celebrating something, definitely Charleston-ing. And there’s generally some vague explanation about bubbly getting you drunk faster—a kind of giddy drunk that typically doesn’t devolve into the weepies or the sleepies. But is that really a legit phenomenon?

The question is actually still kind of up for debate. Over the years, studies have shown that, yes, bubbly booze can indeed help alcohol enter the bloodstream faster, leading to more rapid (but not overall higher levels of) intoxication. But then, certain participants in those very studies showed absolutely no difference in intoxication between bubbly and bubble-free booze. Clearly the question—one of the more delightful scientific endeavors we can imagine—needed more investigating.

Believe it or not, this has been an issue of some importance for a while now. A 1924 study from the Department of Physiology at Bedford College in London—done on an anesthetized cat, whom we assume was treated with a nice hangover breakfast afterward—concluded the following: “With regard to the absorption of alcohol in the presence of CO2 there seems to be a tendency for more alcohol to be absorbed in the presence of CO2, though the effect is not nearly so marked as in the stomach.” No doubt, folks were drinking a bunch of Champagne year-round, it being the Roaring Twenties and all, so maybe the question of whether bubbly gets you hyper-buzzed was a bit more pressing. (Again, it takes a lot of coordination to do the Charleston well.)

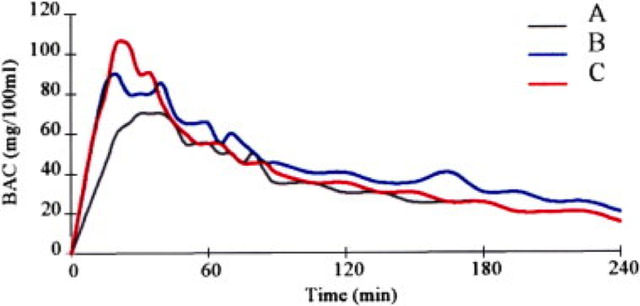

Though the question was specific to Champagne, anything with bubbles can possibly increase the rapidity of absorption. A 2007 study shows that vodka diluted with carbonated water (C) was absorbed faster than both vodka diluted with water and vodka alone. A smaller, and slightly questionable, 2003 study that was actually done with Champagne echoed these results (hard to trust a study with only 12 participants and incredibly surprising they couldn’t find a bunch more people willing to drink free Champagne).

Another study, with a whopping 21 participants, also showed a more rapid rate of alcohol absorption when subjects were given bubbly, as opposed to degassed, Champagne. But seven of the 21 subjects showed no difference in absorption rates when drinking bubbly and non-bubbly, meaning your rate of Champagne intoxication might be exactly the same as your rate of Jager intoxication. (We hope you’re drinking Champagne ‘cause it’s so awesome.) This makes sense, considering that the impact and rapidity of alcohol absorption in individuals can depend on a variety of things, including genetics and digestive factors.

So what about that feeling of giddiness? Why does knocking back shots of whiskey make us want to punch a wall while a glass of Cava makes us want to tickle fight a stranger? (To be fair, that wall’s been giving us the evil eye all night.) Part of the so-called bubbly giddiness might have to do with the particular rate of absorption. Dr. Reuben Gonzales of the University of Texas explains that “within the first 15 to 30 minutes of taking a shot, most people feel a level of stimulation that coincides with the alcohol levels rising in the blood.” Since bubbles supposedly hike up alcohol absorption, you get to that stimulation part of intoxication sooner. The sedative part does follow (can’t be giddy all the time) with a general decline in intoxication. But then there’s always a second, and a third—I think it’s the third?—glass of Champagne.