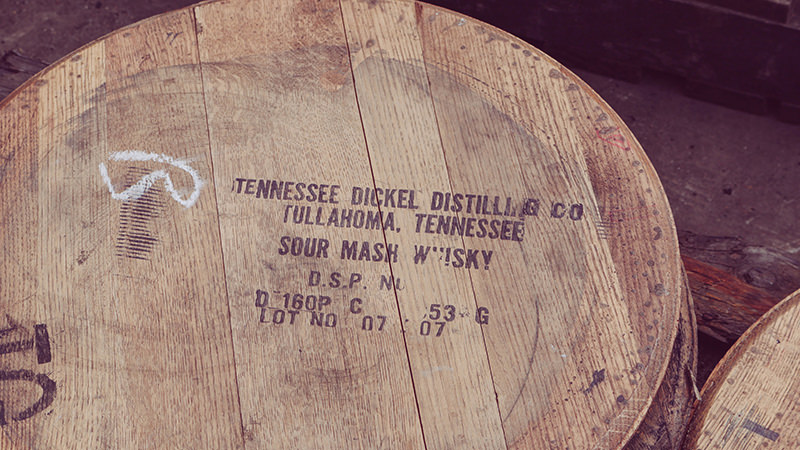

Few places love American bourbon barrels as much as Scotland. Deep in the Scottish countryside, stacks of used American whiskey barrels tower above buildings. Eventually, those barrels will be reworked and transformed, and the barrels that once helped American whiskey become bourbon will be born again as Scotch barrels.

By law, Scotch must be barrel-aged for at least three years, though it’s often much longer. Those barrels are a crucial component in the Scotch whisky production process. Many of them start as 200-liter American Standard Barrels and were used once by bourbon, Tennessee whiskey, and rye producers. Through an involved process, they become 250-liter Scotch barrels fit to be refilled.

One of the largest cooperages that rebuilds those barrels is Diageo’s Cambus Cooperage in the spirit company’s sprawling Blackgrange Scotch whisky complex in the Speyside region of Scotland. The Cambus Cooperage facility is surrounded by pyramids of barrels. Inside, up to 100 people work around the clock to repair and rebuild the barrels — from shaping to toasting to charring. Around 250,000 barrels are put out each year.

VinePair visited the Cambus Cooperage to learn exactly how American whiskey barrels are turned into barrels for Diageo’s single malt Scotch. Inside, even the cool Scottish breeze coming from the open warehouse doors couldn’t shake the smell of bourbon. Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” played in the background as our guide, James Carson, took us from station to station.

The barrels, Carson says, can be used for some 100 years thanks to rejuvenation techniques that bring a barrel back to life.

The first stop — both for us and for the barrels coming into the Cambus facility — was into the hands of a skilled cooper.

The first thing a cooper does with the barrel is identify the staves that were broken during transport.

The broken pieces are discarded and the metal rings holding the pieces together removed.

The barrels then get a steam treatment for 35 minutes to swell the wood and make it flexible enough to handle the shaping and addition of new staves.

Coopers hammer in new staves to expand the barrel and to replace the broken pieces. Scotch barrels must all be a uniform size, which is just slightly larger than the uniform size of the barrels American whiskey producers use.

The new staves stick up slightly higher than the existing ones, and are shaved down by machine. New metal hoops are put on to hold the pieces together.

Scotch barrels that are already the correct size simply need to be rejuvenated before being refilled. The rejuvenation process allows barrels to be used an extra one or two times, and it’s done entirely by a machine guided by artificial intelligence. An automated arm picks up a barrel for rejuvenation with the care a human would pick up a baby. Then the barrel is flame-charred on the inside at 700 to 750 degrees Fahrenheit for two and a half minutes.

The barrels, still warm from being steamed and charred, are swirled around and a top is put on one end. The metal ring is hammered down in five quick hits.

A bung hole for the whisky to be added and tested is drilled. In American barrels, the bung hole is two inches. Scottish barrels require two and a quarter inch bung holes. A natural wax is then put between the joints to prevent minor leaks from happening in the first 10 minutes that whisky is put in the barrel before the wood has a chance to swell.

The barrels are then cooled outside the facility with water.

While much of the manual and heavy lifting portion of barrel repurposing is done by machine today, everything is done by hand at a small apprentice school attached to the Cambus Cooperage. Apprentices manually make three to four barrels a day, learning the craft. It’s a family business where cousins and uncles work side by side, and at Cambus many of the coopers are fourth generation.

The craft isn’t lost despite the machinery. Repairs are still done by hand, as well as certain quality assurance tasks. After everything is said and done, the barrels that once housed American whiskey live a second life in Scotland.