Perhaps it’s time we rethink the term “bourbon barrels.” After all, the charred oak vessels that fill rickhouses in Kentucky and across the country can house bourbon only once by law. And aging bourbon is typically only the first, sometimes briefest, stop on an otherwise epic journey.

Traditionally, that voyage has been one of international travel. Bourbon barrels have sailed the Atlantic to cradle some of the world’s other finest whiskeys in Scotland and Ireland. And they’ve headed south to warmer climes, where they guide the final flavor profile of añejo tequilas and Caribbean rums. And in recent years, we’ve seen an increasing trend of bourbon barrels ending up closer to home, in California wine country and at craft breweries nationwide.

Nowadays, alcohol is only part of the equation. Bourbon-barrel aging has widened its influence across the gastronomic landscape, with products that run the gamut from savory seasonings to decadent dessert toppings. A glance at the category could draw skepticism — bourbon barrel-aged fish sauce? But speaking with producers reveals a commitment to craft that’s every bit as dedicated as that of the distillers who first filled the oak vessels with whiskey.

Welcome to the new era of bourbon barrel-aged products.

Adding Complexity to Savory Sauces

Kentucky-based Bourbon Barrel Foods offers nearly 100 different bourbon barrel-aged products, ranging from smoked salt, pepper, and spice blends to barrel-aged Worcestershire and soy sauces, maple syrup, and sorghum. It’s an impressive lineup, to say the least, but staggering when considering that the founder, former chef Matt Jamie, wrote his business plan in the early aughts with just one product in mind: Soy sauce.

Looking for a way out of the kitchen, Jamie drew inspiration for the unlikely product from parallels between the soy sauce and bourbon industries — their shared processes (fermentation and aging) and rich heritages. If ever there was a moment to combine the two, it seemed like the perfect time. “I felt like I could ride the coattails of the success the bourbon industry was beginning to experience in 2006,” Jamie says.

Since then, bourbon barrel-aged foods have evolved into their own diverse category. Demand for the once-free barrels has skyrocketed. There have been periods when prices hit $200 for used barrels, Jamie recalls, and even points when none could be sourced. Bourbon Barrel Foods also uses damaged staves from reconditioned barrels to smoke products such as its spice blends. Even those have seen modest price increases, Jamie says, jumping from 3 cents per pound to a quarter.

Among its roster of sauces and seasonings, it’s the Bluegrass Soy Sauce that remains the brand’s most popular product. Microbrewed with non-GMO soybeans, each batch ages for one year in barrel before the contents are pressed and bottled. As a subtle nod to the bourbon industry, labels are hand-numbered by batch and bottle.

Michigan-based BLiS Gourmet offers a similarly expansive line of barrel-aged food products. Founded by chef Steven Stallard in 2004, he started by experimenting with barrel-aged maple syrup. When Stallard realized that process only added to each barrel’s potential, he expanded his operation, filling the barrels with other liquids after they’d been tapped of the rich, unctuous syrup.

He started a sherry vinegar solera, which is now in its 17th year. Like Bourbon Barrel Foods, BLiS also now ages soy sauce. But rather than brewing it from scratch, the company imports one-year-old sauce from Japan’s Yamato Soy, then rests it for a further 14 months in former maple barrels.

Other used maple barrels are sent to breweries to age stouts. Their journey isn’t over there, though. When they return, the bourbon-turned-maple-turned-beer barrels house BLiS’s “Blast” hot sauce. After that, they’re filled with the company’s steak sauce.

But the standout among BLiS’ lineup is surely its barrel-aged fish sauce, created in partnership with Vietnam’s Red Boat. “When we first did the barrel-aged fish sauce, it really floored a lot of people,” says Sarah Sherman, BLiS’s vice president of business development. “Friends took it to the Aspen Food and Wine Classic the year we brought it out and people were doing shots of it like whiskey. It’s so smooth.”

The soy and fish sauces leave similarly lasting impressions on their barrels. If their potent flavor profiles weren’t enough to consign the vessels to history, then the corrosive salt content, which proves too much for the barrels’ metal rings, declares “last stop, end of the line.”

Like BLiS and Bourbon Barrel Foods, Vermont’s Runamok Maple also offers bourbon barrel-aged maple syrups. Co-owner Laura Sorkin says aging syrup isn’t without its own sticky complications. The liquid’s 66 percent sugar concentration causes staves to contract, she explains. In five years of barrel aging, the company has yet to find a watertight solution.

“We’ve tried wet towels on the barrels and soaking the barrel on the outside,” Sorkin says. “The best we’ve come up with so far is to put them in a humidified room where at least the outside of the barrel can stay moist.”

Still, the 12-month aging period and slight leakage are worth it for the amber nectar within. “It’s just phenomenal — one of the best things you’ve ever tasted,” Sorkin says.

Bourbon Barrel Flavors in Coffee

Bourbon-barrel aging extends beyond kitchen pantry products. For North Carolina’s Brian and Lauren McCulloch, launching a barrel-aged coffee brand, Oak & Bond, was the perfect way to turn their hobbies into a business. Brian was already a bourbon collector, and the couple’s passion for coffee had taken them to the point of roasting their own beans. They finally committed to launching their brand after looking at the drinks space, and seeing craft brewers age stouts in former whiskey barrels.

“My thoughts was, ‘If they’re able to combine the flavor profiles of a really good beer and a really good whiskey, why can’t we do that with coffee?'” McCulloch says.

Oak & Bond ages coffee in various types of former booze barrels, including Scotch, rye, and Cabernet Sauvignon. But the bourbon barrel-aged blend is far and away the most popular, McCulloch says, adding, “The heightened excitement just for bourbon in general right now is at an all-time high.”

Oak & Bond’s process rests green, unroasted coffee beans in barrels for anywhere between a few weeks and a couple of months. The time period depends on the type of coffee, its moisture content, and the strength of the spirit’s flavor left in the barrel, McCulloch explains.

Colorado’s Whiskey Barrel Coffee goes further, aging its blend for six, seven, eight months — sometimes even longer. The goal, founder Tal Fishman says, is to create a balanced coffee with a notable bourbon finish. Each finished batch is packaged in wax-sealed glass bottles, and, like Bourbon Barrel Foods’ soy sauce, labels receive a hand-printed batch number.

The company’s tagline, “It’s Not Your Morning Coffee,” reflects Fishman’s philosophy on how drinkers should enjoy the caffeinated beverage. The idea of drinking a cup of Joe from a paper cup or during a morning drive to work is just as absurd as shooting fine whiskey, he says. Instead, it should be an “experience” — an act sitting down, enjoying a carefully crafted beverage, and being present in the moment. He’s talking about coffee when he says this, but could easily be describing sipping a dram of small-batch bourbon.

For those who turn to tea for their caffeine kick, there’s Chicago’s Rare Tea Cellar. Owner and master blender Rodrick J. Markus has spent the last 25 years as a tea importer, 10 of which have seen him hone the craft of barrel aging.

Tea is the perfect candidate for the barrel-aging process because of its porous, absorbent nature, he explains. Scenting teas — the practice of infusing leaves with flavors from jasmine flowers, roses, and magnolia — is also steeped in tradition. In the case of barrel aging, the process also softens the tea’s tannins, while brightening its natural aromas and infusing it with typical bourbon notes like banana and vanilla.

Special teas call for unicorn barrels. For its Aged Keemun, one of the rarest black teas in the world (”two grades higher than what the Queen of England drinks,” according to Markus), he hand picked a barrel that previously held 18-year-old Elijah Craig.

“It’s such a wonderful crossover to bring drinkers into the world of tea and bring tea people to bourbon,” he says.

Confectionary Delights

Much like tea and coffee, the cacao nibs used for chocolate production readily absorb the scents and flavors of their surroundings. On the face of it, this would make them seem ideal for bourbon-barrel aging. But while a number of producers have adopted the practice, the influence of bourbon is more subtle in their final chocolate bars than other barrel-aged foods.

Robbie Stout, co-owner of Utah’s Ritual Chocolate, says rather than imparting a whiskey flavor, aging cacao nibs in bourbon barrels rounds out the edges of chocolate’s profile and adds vanilla notes — much like wine or whiskey aging.

To dial up the bourbon influence, he adds a couple of bottles of local whiskey High West, while the cacao nibs age in barrels sourced from the distillery. The aging runs for around three months and once complete, the nibs must be dehydrated before they can be ground and processed. Adding bottles of premium whiskey adds to his costs, and the bars eventually retail for $16 each. But that’s not putting people off.

“When we look at our sales numbers, it’s often one of our highest-revenue products,” Stout says. “People aren’t complaining about the price, because how often do you get to taste something unique and different and special for 16 bucks?”

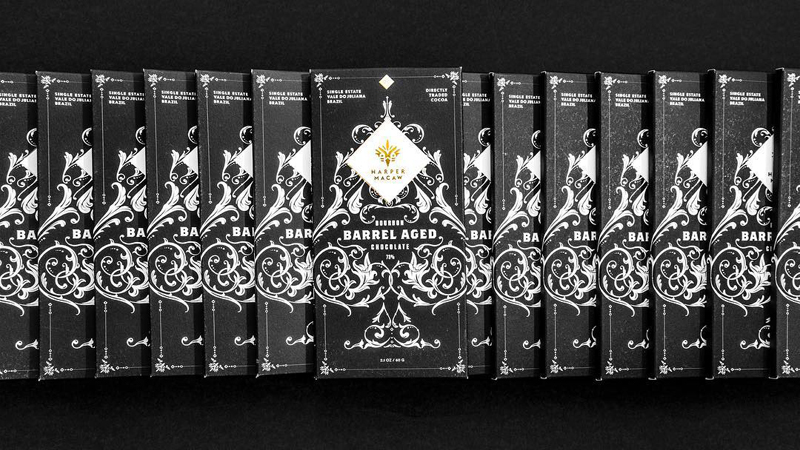

At Washington D.C.’s Harper Macaw, co-owner and chocolate maker Matt Dixon instead increases the influence of aging by leaving the nibs in barrels for periods of up to six months. The potential for taking on any further flavor “maxes out” at around eight or nine months, he says. Even then, it’s the charred oak and vanilla notes that define his barrel-aged chocolate’s flavor, with bourbon lingering in the background.

Dixon also sources barrels from a local distillery, One Eight Distilling. In the past, he’s sent barrels back to the distillery after they’ve held cacao nibs. One Eight Distilling then used them to age a different whiskey.

It’s a familiar tale across all bourbon barrel-aged foods and one that seems to define the category — more so, perhaps, than the liquid it first held. ”The journey of the barrel becomes its own story,” Dixon says.