When cracking open a cold can, it’s easy to overlook beer’s carbon footprint. But if you pause from that first sip and look downstream, from beer can back to barley crop, greenhouse gasses are released at every stage of that beer’s life cycle: in refrigeration, at distribution, during packaging and transportation, and even during farming. (When it’s time to recycle, there’s carbon costs to be accounted for there, too.)

While international brands like Heineken and large craft breweries such as New Belgium have pledged carbon neutrality in the coming years, it’s difficult for breweries on their own to significantly impact beer’s larger carbon footprint.

“We’re just part of a national infrastructure,” says Katie Wallace, New Belgium’s director of social and environmental impact. A single brewery cannot impact how beer, by and large, is transported or packaged.

But recently, new technologies and packaging innovations offer hope that the larger industry can shed unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions.

Packaging — which contributes to more than a third of beer’s overall carbon footprint — “is the last mile when it comes to sustainability,” says Caren McNamara, founder of Conscious Container, a company attempting to create an environmentally and economically viable refillable glass bottle system in Northern California .

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s most recent report, about 70 percent of glass bottles and half of aluminum cans end up in landfills. Producing new bottles unnecessarily contributes harmful emissions, and crushing, sterilizing, and rebuilding materials through recycling isn’t a carbon neutral process, either.

The Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative (OBRC) is a statewide response to the bottle problem. Through OBRC, Oregonians can bag their refillable containers, attach a personal QR code, drop these bags at one of more than 80 locations — on average, OBRC opens two new drop-offs monthly — and receive refund credit, sometimes 20 percent above value. In 2019, OBRC’s 650,000 account holders (in a state with roughly 2.5 million adults, some of whom share accounts with other adults in their households) returned 5.2 million bags to drop-off locations. In 2020, OBRC received 8.3 million bags.

The system accounts for one of the lowest per-container processing costs and highest redemption rates in the world. While no refundable bottles entering the system end up in landfills, and the 1 million refillable bottles in circulation get separated out, the early system needs certain investments to improve efficiency. For instance, there is no bottle washing machine in Oregon, forcing OBRC to ship its refillable bottles to Montana for cleaning, which still, paradoxically, makes financial and environmental sense.

“In a mature system, those returnable bottles will cost significantly less” for both consumers and brewers, McNamara says, citing Coca-Cola’s $400 million investment in refillable bottles in South America. “You don’t invest $400 million in a system unless there’s an ROI there.”

Conscious Container, piloted with the support of Anheuser-Busch, is also attempting to bring a circular economy of refillable bottles to Northern California. But state laws have made it trickier, forcing McNamara to focus on legislative battles first. Conscious Container recently helped push a bill through the state legislature to prevent recycling machines from crushing refillable bottles, yet there’s other bureaucratic red tape. If it wants to incentivize its customers with an offer above deposit rate, as OBRC does, Conscious Container needs to fight to overturn an archaic California statute prohibiting additional incentives for returning used alcohol containers.

Other packaging systems are in place across the industry to reduce beer’s carbon footprint. MicroStar focuses on logistics through a keg share program, ensuring that brewers’ kegs never have to travel the return journey empty. After a keg gets kicked, the empty container is sent to another nearby MicroStar customer so that it can be refilled and shipped full. There are also two new technologies that remove water from beer, which is essentially 95 percent of the beverage.

In Golden, Colo., Sustainable Beverage Technologies (SBT) created BrewVo, a machine that sends beer through a multi-brewed fermentation process, which founder and chief technology officer Pat Tatera calls “nested fermentation.” The process involves brewing a typical beer, removing the alcohol, and then brewing another batch of wort inside the brewed beer, allowing additional fermentation to take place. The alcohol is continually removed and new batches of wort are continually added. These repeated fermentations eventually yield a thick concentrate, like soda syrup, which can be packaged in bags that ship eight times more efficiently than cans or bottles, according to Tatera, since the beer is both concentrated and the bags have better pallet density than their cylindrical counterparts. And because SBT’s beer concentrates travel at one-sixth the normal weight and volume, the company is providing opportunities for the industry to eliminate many of the greenhouse gas emissions that come from packaging, transportation, and refrigeration.

Using another SBT technology, bars or breweries can add the alcohol (which is bagged separately) back into the beer concentrate when it’s rehydrated and carbonated. Interestingly, alcohol levels can be adjusted in the final product without affecting flavor. Customers can therefore order a full-strength beer or non-alcoholic (NA) beer that virtually tastes the same.

While it might be peculiar to consider drinking a once-concentrated beer, BrewVo-brewed beer has won gold at the Best of Craft Beer Awards in a category with many well-regarded session IPAs and bronze at the Australian International Beer Competition.

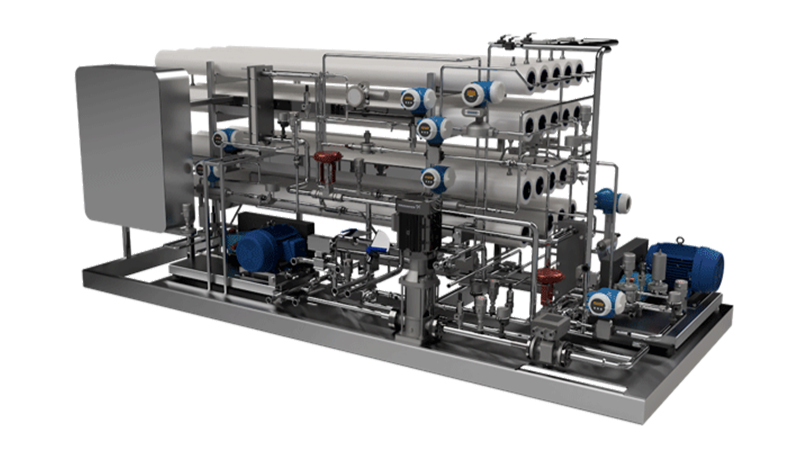

In Sweden, Alfa Laval’s Revos Beer and Beverage Concentration machine also removes liquid from beer through reverse osmosis, which takes place at the end of the brewing process. Its inventor, Ronan McGovern, claims that Revos’s beer concentrates are approximately five times more efficient to transport than bottles, cans, and kegs.

While there’s a clear benefit to transporting quality beer concentrates, the challenge is to get brewers to recognize and respect the environmental benefits of these products.

For instance, one craft brewery uses the BrewVo system because it produces high-quality NA beers. However, once the brewery receives its bagged concentrates from Colorado, the beer gets reconstituted and canned in Oregon, and is then shipped to the East Coast — canceling out the greenhouse gas emissions that had been reduced by the technology.

Carbon dioxide released during fermentation is considered net zero — it’s released from sugars but removed from the atmosphere during photosynthesis — yet capturing this carbon certainly helps. Not only does it pull carbon from the atmosphere; capturing carbon dioxide eliminates the need for brewers to purchase and ship CO2 tanks to their facilities.

For years, large breweries have owned and operated warehouse-sized systems that capture carbon. But for small breweries, owning such a system was never realistic. In 2018, however, Earthly Labs launched CiCi, a small machine that uses foam traps to capture carbon dioxide from the brewing process, stores the carbon, and converts the gas into a chilled and purified liquid. This end product can be recycled back into the brewing process, pumped into packaging, or used to move beer through tanks. Earthly Lab’s founder and CEO, Amy George, estimates that CiCi’s cost is recouped by most breweries within a few years, as brewers save on purchasing CO2, which also happened to be in short supply last year during the ongoing pandemic. SBT’s CEO and Revos’s inventor offered similar estimates for the time it takes to recoup the costs of their machines.

Some breweries are even using CiCi to resell their captured carbon. One Earthly Lab customer, Denver Beer Co., transports 60 percent of its captured carbon to nearby marijuana farms, where the liquid is vaporized to enhance indoor photosynthesis and increase the plant’s yield and potency.

“We’ve turned a waste stream into an income stream,” says Charlie Berger, co-founder of Denver Beer Co. “CO2 recapture will be the norm in the beer industry because this technology is now available. It makes business, climate, and market sense.” It might also make product sense. The Denver Beer Co. added CiCi-captured gas to one batch of beer and injected commercial gas — a byproduct of ethanol production — into another. And because the gas captured with the CiCi machine is free of “the nasty, volatile, organic compounds” found in commercial gas, Berger explains, the Denver Beer Co. team had noticed a difference in taste.

Today, a typical 6-pack might only go for $10 to $20. But in the foreseeable future, if the beer industry fails to address greenhouse gas emissions, that pack could cost more than five times the price. On International Beer Day last year, New Belgium raised the price of its Fat Tire 6-pack from about $12 to $100 to show what beer might cost when climate change causes ingredient scarcity.

Outside of drinking locally, climate-conscious beer lovers can enjoy products from breweries that are incorporating environmentally friendly technologies, considering carbon footprint-lowering innovations, and partnering with local systems that will allow everyone to drink quality products at reasonable prices for years to come.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!