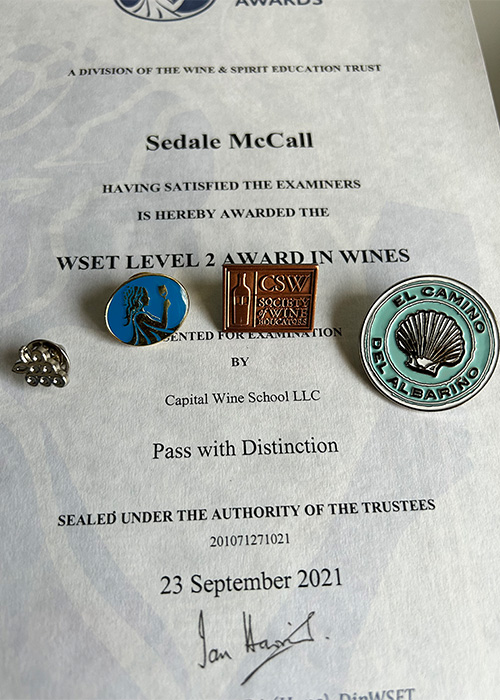

CSW. Certified Sommelier. WSET Level 2, with Distinction, of course.

Certifications are either the beginning or the end of most biographies in the wine industry. Whether or not they’re required or even relevant, they seem to define who industry professionals are — their status, how far along their wine journey they are, and even, to an unfortunate extent, their socioeconomic backgrounds.

I got started the same way many do in this industry, with wine education. I first sat for the Wine and Spirits Education Trust (WSET) Level 2 exam. WSET has four levels; the fourth is known as Diploma level, one of the toughest exams in the industry. After passing Level 2 “with distinction,” I knew I should prepare for Level 3. I had been told Level 2 shows a certain level of knowledge but I would be truly taken seriously as a professional with a Level 3 certification. So I took other courses through the Society of Wine Educators and Napa Valley Wine Academy. I’m still on this journey today.

Along the way, I’ve met others in the industry who are on this journey. WSET Diploma hopefuls, and even candidates for the Master of Wine, an even more daunting exam. I’ve spoken to organizations that provide resources and scholarships for those seeking such high-level certifications.

But I’ve also spoken to industry professionals who aren’t certified at all. Sommeliers, wine shop owners, writers, winemakers. Many of them claim experience is the best teacher and not, well, teachers.

But how did they do it? Can individuals gain experience without formal education today? And more importantly, are we all wasting time, money, and energy on wine education and wine certifications when practical experience may prove more relevant?

Wine Education’s Very Expensive Alphabet Soup

Another well-known educational institution is the Court of Master Sommeliers (CMS). Many of the most influential wine documentaries — “SOMM,” ‘Uncorked,” etc. — focus on the Court’s Master Sommelier exam. Being an “MS” is one of the most prestigious titles in the business. Even with an established history of racism, sexism, and sexual misconduct plaguing the organization, those who take and pass the exam are viewed as the foremost experts in the field, similar to Masters of Wine.

However, the barriers to entry for these exams are enormous. The MS exam costs $3,000, after the Advanced exam — a requirement for the MS exam — which is another $3,000. The MW can cost up to $13,000, and often that’s after taking WSET Level 4, which has six parts ranging from $400 to $3,000 each. None of these figures take into account the cost of preparing for each exam, including buying countless bottles to hone blind tasting skills.

“You need balance to be a good member of the wine industry. If you only have certs and no experience, you haven’t been hands on, there are limitations to your contributions.”

So far, assistance has arrived in the form of scholarships for those who cannot afford to spend $20,000 to pursue the highest levels of wine education. Organizations like The Roots Fund, Wine Unify, and SommFoundation are working to level the playing field by helping professionals get the education they need to succeed in wine.

These are all appealing options to me, but in the past year, I’ve seen another path that’s equally attractive. I had the opportunity to intern at Early Mountain Vineyards in Madison, Va., for a week. I learned a ton from winemaker Ben Jordan and the team, and now have a personal attachment to the 2021 rosé and Petit Manseng, which I helped produce. I’m also participating in Oeno Camp, funded by The Veraison Project. This organization is providing experiential opportunities for minorities hoping to enter the industry.

These are exceptional learning opportunities. But is that enough? Would my experiences alone show employers and other wine professionals my knowledge of the industry without the certifications?

I’m not sure.

Trust the Experts

From the outside, it seems like employers aren’t as concerned about certifications as we think they are, but organizations and wine enthusiasts continue to pursue them as a way to get themselves and others into the industry.

“Let’s leverage this global education that means the same thing all over the world. If we give people a tool [education] to function within [the system], then change can come about.”

“I don’t believe testing is the best way into anything. I feel that it’s exclusive,” says Jessica Outer, vision and marketing director of Unwined, a wine shop in Alexandria, Va. Neither she nor owner Vanessa Moore had wine education until later in their wine careers. “If you’re saying that this person who can retain information and put it on a piece of paper in an hour is better than someone who can’t, that is not the way anything should work,” Outer says.

But if wine certifications aren’t the best way to secure jobs in the industry, what’s education for?

“Education is a tool. It’s not enough to change the system, but it’s a start,” says Mary Margaret McCamic, who is an MW and one of the founders of Wine Unify, which provides scholarships for WSET exams to underrepresented groups. “Let’s leverage this global education that means the same thing all over the world. If we give people a tool [education] to function within [the system], then change can come about.”

In speaking with her, I learned that the Institute of Masters of Wine requires “active professional involvement in the wine industry” (at least 20 hours per week) and “a minimum of three years of current and continuous active professional involvement in wine at the time of submitting your application.”

While I applaud them for encouraging practical experience during the process, it is a bit ironic to me that an education institution would require experience, while so many believe they need the education in order to enter the industry.

Perhaps, we’re thinking about wine certifications in the wrong way. It’s not that wine education is losing its value, it’s that the value is shifting.

“You need balance to be a good member of the wine industry. If you only have certs and no experience, you haven’t been hands on, there are limitations to your contributions,” says Noelle Harman, wine educator, blogger, and current MW Stage 2 candidate. “You can learn a lot more by doing. But if you take an exam, I know you are driven, you will show up and commit.”

My Conclusion

At the end of the day, entering the wine industry and taking exams should be distinct goals. To enter the industry, there are plenty of opportunities and employers will not disqualify candidates for not having formal wine education. Wine education is about expanding your own knowledge, which should be a personal pursuit.

Practical experience like spending time in wine shops, wineries, or restaurants shows potential employers a candidate’s skills and knowledge, even if they don’t have a certification.

On the other hand, wine certifications show employers (and other wine professionals) something different. It shows a commitment to improving your knowledge, and a willingness to spend the weeks — or even years — of time to complete the course. It can also show curiosity and thirst for learning. Those are transferable skills that can give an advantage in competitive job markets.

I love learning, and the courses I’ve taken are a clear complement to the experiences. But the costs for my next levels of wine education are difficult to justify. Thankfully, there are scholarships available, and I will need them.

My advice to others is to find mentors first who can help show the balance between education and experience. Never take a course to get a job or prove proficiency. It will not show a return on that investment.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!