As an immigrant who came to the United States from Hong Kong more than 20 years ago, one thing I always remind myself to do is to pursue the American dream. What is my American dream? I have a decent job in corporate America, raise my family in a safe neighborhood, run a few marathons to fight the mid-life crisis — and, of course, enjoy a fair share of American fast food. Life is good!

Embracing the freedom of speech that is protected by the First Amendment, I started a website that focuses solely on blogging about pairing Chinese food and wine (made out of grapes). The blog was born nine years ago, but believe it or not, up till now, I still face the problem of prejudiced pairings when it comes to Asian cuisine and wine.

In my blog, the food is Chinese, but the wines to pair with it are red, white, pink, or blue, from the New World or Old World, intending to showcase the limitless pairing options. By no means am I an expert in the many regional cuisines that originated from China. But when you grow up in a place like Hong Kong, where enjoying foods and cuisines from all over the world is a way of life, I am blessed with a trained palate and am forever motivated to pursue gastronomic pleasure. In particular, top-notch regional cooking and ambitious entrepreneurship were brought to Hong Kong by some of the most skillful restaurateurs among the Chinese mainlanders who emigrated there during the 1970s.

Adding continued education on wines through organizations such as the Wine and Spirits Education Trust (WSET) and learning through reading wine articles from renowned wine writers gave me confidence. Feeling cocky, I said to myself: “There shouldn’t be many people out there who know how to pair wines with Chinese food better than me! At least, not in the U.S.”

As my blog and wine knowledge progressed, I began to attend and was hired to pour wines at wine events. Little did I know, regardless of the venue — conferences, tasting events where I attended as a consumer or server, or even private parties — strangers started to offer their wine pairing ideas the moment they found out the theme of my blog. Occasionally, I did appreciate some people’s breadth of knowledge in this very niche topic and their genuine curiosity. However, most of the time — more than I liked — people would say something along the lines of the following remarks.

“Wow, what you do is very interesting. So, what wines do you recommend pairing with Chinese food? Riesling and Gewürztraminer?”

Or, some folks enthusiastically offer, “The sweet Moscato would be so good with the spicy Sichuan General Tso Chicken! That’s my favorite Chinese dish.”

General Tso Chicken tastes great, for sure. However, as a Chinese history buff, I’ve never heard of General Tso or a historic war this man had fought. This dish does not originate from the faraway land, Sichuan, but is simply a dish made in the U.S.A. to cater to the American palate.

Where is all this narrow-focused wine-splaining coming from? The supply chain of the wine industry — production, distribution, promotion, marketing, sales, reporting and blogging — is traditional and strives to maintain the status quo. Diversity to include people of other ethnic backgrounds into the proverbial food chain is seeping through, somewhat slowly, and hopefully surely.

At recent wine conferences, including the 2021 virtual Symposium for Professional Wine Writers at Meadowood Napa Valley and the 2020 virtual SommCon Summit, I learned about the lack of diversity in wine writers. In the recent past, when wine writers who were established “de facto” were given writing tasks to write and explain how ethnic foods paired with wines, they went by what they knew and what was typical. These writers may be given an assignment to write about pairing Indian food with wines that’s due the next day, and what do you know? Butter chicken paired with off-dry Riesling!

There is a bit of sarcasm here, but it’s not far from the truth. Readers who consume this information from a homogenous group of writers get the same ideas repeatedly. Sweet and off-dry Riesling, Gewürztraminer, and Moscato are subliminally stuck and unconsciously reinforced as the go-to wines to pair with Chinese, Indian, and Asian food. Even nowadays, when you can Google the phrase “Chinese food and wine pairings,” these same wines are still listed as the “best” pairing wines for Chinese food.

What if you were to venture out of your comfort zone? Dare to try lightly oaked Saperavi from Georgia with five-spice cubed lamb on skewers at your next barbecue. Splurge a little bit for Thanksgiving and have a Cru Beaujolais with soya sauce-braised whole chicken. For white wine drinkers: Tell me what you think after trying a dry Oregon Viognier with Cantonese-style ginger and scallion lobster. An open mindset can reduce bias — and tickle the taste buds!

I was never bothered by the occasional stares or even mocking of my Chinese-accented English. I used to see it as a slight disadvantage that my tongue couldn’t twist the right way to make the perfect sound. As I age, I see my face and voice as my unique identity, how people will remember me.

However, having a Chinese appearance and accent means I get the Penfolds ask a lot as I am perceived as the affluent wine lovers from Mainland China who have a love affair with Penfolds until the recent trade war between China and Australia that consequently jacks up the tariffs of Australian wines in China: “Do you have a collection of Penfolds? People from China love their Penfolds. Which one do you like the best?” Some people start to get in the weeds by telling me they love Bin 389 but find Bin 149 a bit overrated. I feel a bit defensive when I need to first correct the person — I am originally from Hong Kong, which was not ruled by China when I left in the 1990s — but what truly annoyed me is that I never even tasted the $65 Bin 389 and the $149 Bin 149. God damn it! I think to myself, I wish I were as privileged as that Chinese person they are talking about!

My heart shattered when I saw on the news that an Asian family with a toddler was stabbed in a Sam’s Club in Texas in April last year. I immediately ordered pepper spray from Amazon and have kept it in my purse since then. I was saddened to resort to this and a flimsy face mask to protect myself, to help hide my identity, which had become a liability.

Chinese Restaurants Affected by Asian Hate Crimes in NYC

The attacks against Asian Americans have increased steadily since the onset of the pandemic. Unfortunately, these events skyrocketed at the beginning of 2021. I stopped by a few Chinese merchants in Chinatown in Manhattan in early June and experienced firsthand the fear brought by the surge of random violence and economic devastation due to Covid-19.

Ming Chan (alias), the third-generation owner of an 82-year-old wine and liquor store in Chinatown, spoke about how his business significantly slowed down due to fewer new customers stopping by. “Although the regular customers who live in Chinatown came back steadily the moment the government lifted the lockdown in June 2020 for liquor stores, fewer tourists are visiting Chinatown, a tourist hotspot in New York, in light of the spike in hate crimes,” he says.

As the cash-based operation is a norm in Chinatown, Chan added that he has been very cautious when depositing the cash the business makes for the day in the bank in the early evening.

“We are very lucky that we have not been robbed,” he says, “at least not yet!”

Kam Han Lee has been a restaurateur in Chinatown for over 40 years. Waiting to open another new casual-dining Chinese restaurant on Mott Street in a few months, Lee currently works as a marketing representative and street vendor for Lee Kum Kee, a household brand of Asian cooking sauces, in an outdoor setting across the street from his store. He says the recent hate crimes affect him as a street vendor.

“I used to work until midnight in the past. But I must pack up and go home at around 7 p.m., before the sun goes down,” Lee says. He feels there’s less police presence compared to pre-pandemic and doesn’t trust that he’d get timely support when help is needed.

Deluxe Green Bo Restaurant has been operating at Bayard Street for six years, serving the best Shanghainese noodles, steam buns, and many vegetable side dishes. Along with manager Angela Tseng, the other two female staffers do not feel safe taking the subway at night. Tseng describes a recent incident that was extremely upsetting to witness: A middle-aged Chinese woman was punched in the face by a man in broad daylight on Memorial Day. It happened across the street from the restaurant. This violent incident was caught on the security camera and broadcast on national TV.

“The attack was unprovoked and vicious. We are outraged but can’t do much to stop these heinous crimes,” Tseng says. While the three women are disheartened to work in fear, they don’t think they have an alternative, as they have to work to make ends meet.

New Golden Fung Wong Bakery on Mott Street specializes in traditional Chinese pastries such as egg tarts, hopias, moon cakes, and Zongzi (Chinese tamale). Kelly Wong (alias), the current owner of this 64-year-old store, has witnessed all sorts of ups and downs throughout the years. Still, by far, the economic loss resulting from the reduced number of customers and the pandemic shutdown has hit the hardest.

“The elderly women are amongst our most regular and loyal customers,” Wong says. “Right now, they see their peers are subject to these vicious attacks, they just don’t go out shopping.”

For New Golden Fung Wong, the road to recovery is long; Wong says the money her business currently makes daily is only enough to cover costs. The business has yet to make a profit.

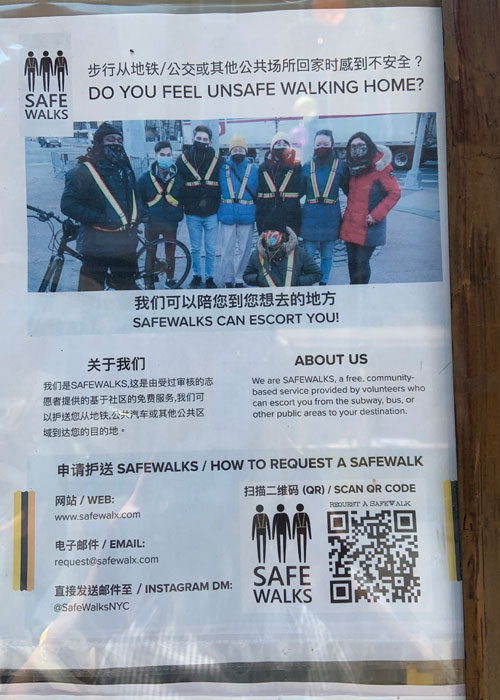

Despite the distress and economic turmoil brought by the recent hate crimes and pandemic, the resiliency and agility of these businesses are evident. Community support is available from organizations such as Asian American Legal Defense Education Fund and Stop AAPI Hate to help residents resume normalcy, minimizing the debilitating impacts of hate crimes. A great team of volunteers has formed a free service called Safewalks to escort Chinatown residents from subways, buses, or other public areas to their destinations.

Ming Chan, the liquor store owner, left me with this:“There is always a workaround! There is an old Chinese proverb: When soldiers march to your village, the community puts together a troop to fight back; when water starts to flood the road, you assemble sandbags. Life goes on!”