At the inaugural Beer With(out) Beards festival in Brooklyn last summer, attendees lined up for Black Project, a Denver, Colo., outfit specializing in spontaneous and wild ales. Behind the table, with a bucket of bottles and opener poised at her hip, stood Sarah Howat, Black Project’s operations manager.

Sour and other spontaneously fermented or wild ales have become increasingly popular among American beer drinkers. Sour beer sales in the U.S. quintupled from 45,000 to 245,000 cases from 2015 to 2016, and they continue to rise.

Sour beer-making techniques are expanding in turn. Small and scrappy upstarts like Black Project, Oregon’s Solera Brewing, Oklahoma’s American Solera, and their slightly longer-established forebearers, are melding Belgian brewing traditions with tricks of the wine and whiskey trades.

One process undergoing a domestic renaissance is solera brewing. Originally used by Spanish sherry producers in the 1800s, the solera method is now being adopted by award-winning brewers like Cambridge Brewing, which claims to have created “the first true solera system in the U.S. for beer” in 2003, and Beachwood Blendery, whose first attempt at a Belgian-style gueuze recently took home a gold medal from the Great American Beer Festival.

As both experiments and creative expressions, no solera beer can be replicated, making this emerging category the apex of craft beer art and science.

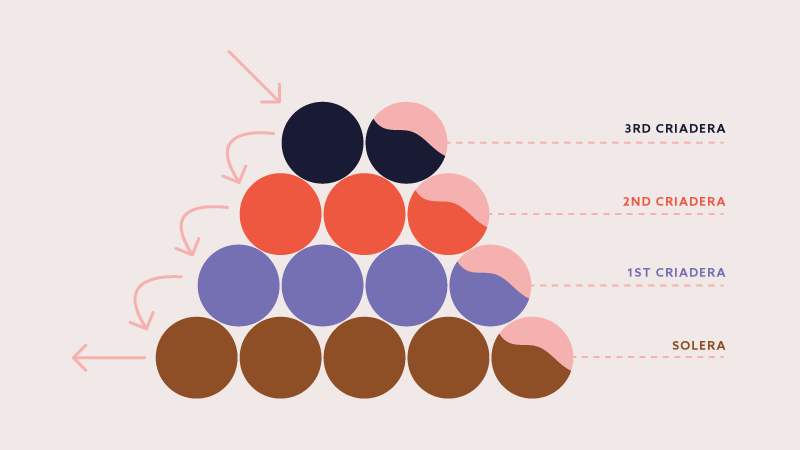

The term solera is used to describe a system of aging in which batches of liquid are funneled into vessels, traditionally oak barrels or casks, at various stages. In addition to sherry, European producers have used this method for port, brandy, marsala, and even some vinegars, like balsamic.

The base layer of the structure is the solera, a word stemming from the Spanish suelo meaning ground, floor, or soil. The next stage is the criadera, a set or sets of barrels above the solera; and atop the criadera is sometimes called the sobretables. Each time a new batch of liquid is produced, a portion from the bottom is emptied, filled back up with contents from the stage above it, and so on.

In recent years, distillers have used the solera method to age whiskey and rum as well. In 1997, Glenfiddich’s former malt master David Stewart devised a 38,000-liter vat made out of Oregon pine to be used as a marrying tun. Stewart is credited as “the first to do additional cask maturation,” Allan Roth, Glenfiddich brand ambassador, says. The solera vat was filled, and has remained at least half full, since Glenfiddich started bottling from it in 1998.

Today, Glenfiddich uses a singular vat for each of its five solera expressions. The most well known is its 15 year expression. “Having this continual mixing of batches has made this an incredibly consistent whiskey with an incredible depth of flavor,” Roth says. “Instead of just marrying each batch in 2,000-liter vessels for a few weeks, we’re having all of the different versions married together in perpetuity.”

The first recorded use of the solera method by American brewers traces to Ballantine Burton Ale, debuting in the 1930s but discontinuing in the late 1960s. Nearly 40 years later, big-name craft brewers launched special limited-edition beers using solera techniques. New Belgium is credited as the first sour beer producer in the U.S. for its famous La Folie, a Flanders-style sour brown ale aged in oak barrels. It has been released annually since 1998.

Solera brewing is particularly well suited to sour beers and other mixed-fermentation experimental ales that benefit from the method’s ultimate result of complexity and consistency. Boston Beer employs more than two decades’ worth of casks of all kinds for Samuel Adams Utopias, which it has released about every two years since 2002. Today, the Samuel Adams Barrel Room Collection continues with its Kosmic Mother Funk (KMF) series of Belgian-inspired ales aged in Hungarian oak tuns for over a year, and fermented with microorganisms like Brettanomyces and Lactobacillus. Dogfish Head, which recently launched a new wild beer program, has played around with the solera technique for sours like the lambic-inpsired Festina Lente and wood-barrel-aged Raison D’Extra released in 2003.

Now, experimental brewers are not saving solera methods for special biannual releases; they’re making a majority of their beers this way. Black Project uses two methods to achieve its coveted creations: spontaneous and spontaneous solera. In the former, a batch of beer is brewed, transferred to a coolship where it sits overnight to pick up airborne microbes, and then transferred in the morning to empty, steam-cleaned barrels. For spontaneous solera batches, beer moves from the coolship to a setup of stainless square totes, where beer, along with its yeast and bacteria, stick around from batch to batch.

“It’s a modified solera because we’re emptying from one vessel and refilling into that vessel,” Howat says. She estimates Black Project’s spontaneous solera is at least three years old.

In solera brewing, blends can vary. Black Project “might blend 10 percent of one tote, 30 percent of another, and 2 percent of another,” Howat says.”Then we’ll refill up to the brim whatever we emptied.”

A brewer can also bottle straight from the square tote. These “base beers” are typically aged on fruit, hops, or both, but can also be released on their own, as is the case with Black Project’s Dreamland.

A fascinating aspect of adapting the solera method to making beer is that each brewer’s interpretation is slightly different. This can be because of creative preferences, but also has a lot to do with space and other resources available.

Black Project was initially limited on space, so Howard and her team lined up their stainless vessels in a narrow hallway. The operation has since expanded, and so they have scaled up and introduced new aging conditions. “Now we have 140 barrels, a handful of puncheons, and a little foeder,” Howat says. “At the time it was just a way for us to innovate and kind of get the result we wanted with the space we had.”

One of the first brewers to go all in on the solera method was Cambridge Brewing, which released its first of many solera beers, Cerise Cassée, in 2003. At Crooked Stave, founded in 2010, Brettanomyces-flecked oak foeders are filled with about 70 percent young beer and 30 percent beer that’s ever-increasing in age and complexity, each tapping awaiting its blend with other barrel-aged sour beers.

Solera Brewery, founded in 2012 in Parkdale, Ore., devotes its brewing to the method. California’s The Bruery launched an entirely separate operation, Bruery Terreux, devoted to sour blends made with the solera method in 2015. And American Solera, founded by Prairie Artisan Ales’ Chase Healey, was named the best new brewery in the U.S. at the RateBeer Best Awards in 2017.

What makes solera beer so exciting — and, for many, more interesting than its grape-driven ancestors — is its unforeseeable future. Whereas wine and spirits age in a solera almost undisturbed by the world around them (whiskey and wine being too high-proof for yeast or other microorganisms to survive), beer is biologically volatile.

“You don’t know if something is going to take off,” Howat says. “It’s unpredictable … I love it.” Things like time, temperature, and, ultimately, flavor profile are out out of brewers’ control until the blending phase.

“You get layers of complexity that you wouldn’t otherwise get from a single barrel on its own, single vessel on its own, or single batch on its own,” Howat says. “Each time we brew into that vessel, the yeast and the microbes that are in that beer already are going to chew on that wort at varying rates, depending on what the stronger microbe is at the moment.”

And despite its labor-intensive nature, over time, solera brewing is a more effective way to brew a consistently complex product. Solera Brewing is able to achieve “a constant flow of complexly layered, acid-forward beers without the long wait,” Jason Kahler, brewmaster and co-owner, told CraftBeer.com. “[I] quickly realized that not only was this a simple way to feed and keep the critters active, but also produce a beer that had some aged qualities that could be achieved in a fraction of the time.”

At Black Project, what used to take nine to 12 months to create is now accomplished in six. “It’s definitely sped up and it’s become a lot more consistent, but it’s also become a lot more complex over time,” Howat says.

*

Solera beer is a creative contradiction to modern tastes, a time-consuming pursuit that can’t be rushed or swiftly changed. It’s the opposite of the New England IPA, a fast-moving category of beers brewed and sold as fast as they fall off.

Solera beers, however, combine creative blending with a mix of microorganisms that demand time, patience, and chance. We’re more than willing to wait for the next stage.