This weekend American Pharoah and his owner Ahmed Zayat achieved history by becoming the first horse since 1978 to win the coveted triple crown. This is no easy feat and to accomplish it takes an immense amount of time, investment and a passion for the sport. In Ahmed Zayat’s case, it also takes the ingenuity to sell beer so profitably in a Muslim country that outside corporations take notice.

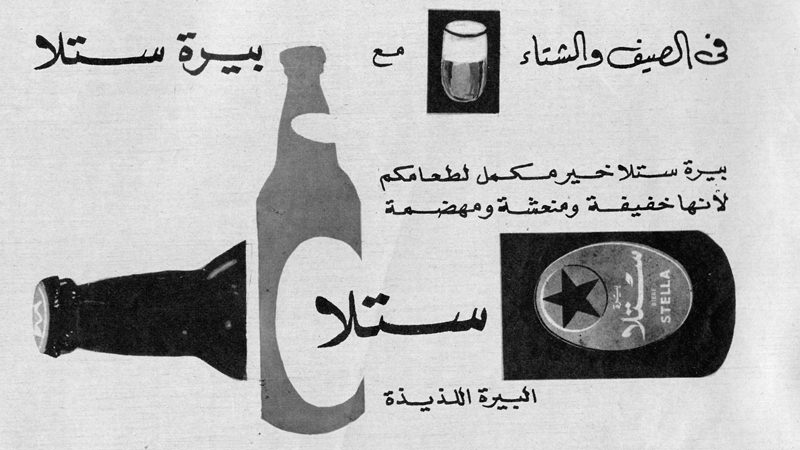

While now based in the U.S., Zayat began his career in his native Egypt. Egypt has always been a country with an odd relationship to alcohol. While it is forbidden by religious Muslims, modern breweries have existed in the country for decades. Many in the country even draw the birth of beer itself back to ancient Egyptians, yet its consumption in the present day is more problematic and frowned upon than it once was.

In 1897, Belgian businessmen founded Crown Brewing, with the intention of serving expatriates as well as the Egyptian middle class. Many Egyptians at that time were attempting to westernize, and beer was seen to be an aspirational social beverage that was consumed during informal business meetings by upper management. A year later, the same entrepreneurs founded Pyramid Brewing, and for a little over 60 years the companies achieved success among the Egyptian population, as well as foreign support and investment from Heineken. Egypt looked to be well on its way to building a robust brewing economy and Pyramid even renamed itself Al-Ahram, becoming a proudly Egyptian company. The Egyptian brewery industry had arrived.

But then in 1956, when Gamel Abdel Nasser came to power under Arab Socialism, the private brewing industry began its march toward its steady decline, and by 1963, Nasser had wrested control of the brewery from private hands and nationalized Al-Ahram’s operations. Heineken no longer had a stake in the business, and consumption began to wane.

By the 1980s, with Nasser dead and Egypt becoming a more religious Muslim country, the products of Al-Ahram began to be seen as immoral. While it would have been a normal occurrence up to this point to see a poster or a billboard for one of the company’s beverages, consumption was now done in private, and the advertisement of these products was limited. No one was buying the beer, and both sales and quality were on a significant decline.

While many would see these developments as the final nail in the coffin for the Egyptian brewery industry, Ahmed Zayat saw a unique opportunity. In 1997, Zayat raised $70 million dollars from investors and convinced the Egyptian government to allow him to buy back and once again privatize the brewery’s operations. He then set out to not only resurrect the brewery’s former beers, but to create a non-alcoholic beer that would appeal to religious Muslim consumers. With the majority of the Middle East becoming more religious, a non-alcoholic beer was truly the way to find success and gain market share.

Unfortunately, the problem with most non-alcoholic beers is that in the early stages of the product’s creation, some alcohol is still created. And while there’s never any alcohol in the finished product, this early stage creation of alcohol prevents the beverage from being labeled Halal. Without a Halal certification, the beer won’t be consumed by devout Muslims, regardless of whether or not the end product in non-alcoholic.

Realizing that Halal certification was the key to the product being successful, Al Ahram set out to create a malt beverage with a total absence of alcohol from start to finish. What they wound up creating was the product Fayrouz, a fruity, malty beverage that tastes oddly similar to beer, but with no alcohol whatsoever.

After the creation of Fayrouz, the product was brought to Al-Azhar, the most prestigious university in the Sunni Muslim world, for study and certification. With its certification in hand, Fayrouz became the world’s first Halal certified non-alcoholic beer attaining a market position that no other competitor in the world had achieved. This certification automatically gave Fayrouz a competitive advantage with 1.3 billion Muslims. In 2000, they introduced the first flavor, pineapple, and the company quickly sold 1.8 million gallons. The pear flavor, which came a year later, also quickly sold out after its debut. Suffice it to say, the big beverage conglomerates took notice.

Seeking access to a major population of people who had begun to turn away from alcohol for religious reasons, Heineken came calling, buying Al-Ahram in October 2002 for $280 million, quadrupling the value Ahmed Zayat had paid for it only five years before. Zayat’s bet had paid off; he created a product the population would accept, and revived the Egyptian brewery industry in the process.