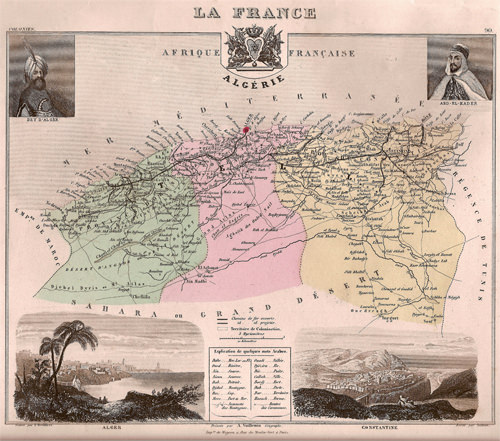

When France seized Algeria as a colony in 1830, the country produced virtually no wine. Fifty years later, as Phylloxera ravaged French vineyards, plantings and production in Algeria soared. By the 1930s, Algeria had grown into the world’s largest exporter of wine, a title it largely held onto until 1962, when the French ceded control of the country. Over the next three decades production and exports gradually collapsed. How did a North African nation – where 80% of the land is desert – quickly grow into the world’s largest exporter of wine, only to vanish from the global markets a few decades later? The story begins and ends with France.

Phylloxera, Technology & A Colony

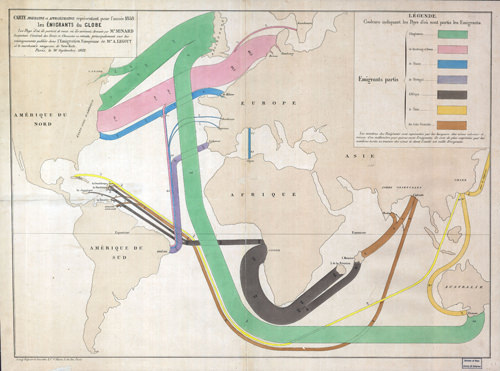

France invaded Algeria in 1830. The conflict raged for a decade and a half. When it was over France had a colony to its south, across the Mediterranean Sea. Colonists began to replant ancient Phoenician vineyards, but there wasn’t much urgency to the effort until the 1860s when Phylloxera, a pest that feeds on the roots and leaves of grapevines, ravaged France’s vineyards. Production in France collapsed from a peak of 84.5 million hectoliters of wine in 1875 to only 23.4 million hectoliters in 1889. While French wine production would recover in time, aided by cuttings grafted to American rootstock, farmers and winemakers faced economic ruin. Tens of thousands of families fled south to Algeria, where recent technological advances enabled commercial wine production. Wine production is only possible in Algeria in its northern, coastal regions. Even so, until the innovation of refrigerated “cold fermentation,” the temperature there was still too high to support large commercial winemaking operations. Louis Pasteur’s mid-century documentation of the fermentation process (which you can read more about here) was the catalyst that led to this innovation. Combine a devastating crop failure, cultivable land in a recently conquered colony, and technological advances in winemaking and you had the recipe for an exponential boom in Algerian wine production. Vineyards in Algeria took time to grow and expand, so in the interim French wine imports from countries like Spain and Italy rose. Acting under a strained definition of nationalism, the French government promoted Algerian wine production in order to ward off those growing imports. The results were astounding, especially considering the day’s technologies for production and transport:

- 1854: 25,000 Hectoliters (660,000 Gallons)

- 1872: 200,000 Hectoliters

- 1885: 1 Million Hectoliters

- 1900: 5 Million Hectoliters

- 1915: 10 Million Hectoliters (264 Million Gallons)

By the turn of the twentieth century, wine was responsible for half of Algeria’s exports and nearly a third of its GDP. The share of exports would continue to rise, but rapid success had already sowed the seeds of what would prove to be an equally stunning decline.

The French Turn On Their Savior

We wrote that France promoted wine cultivation in Algeria in a ‘strained definition of nationalism.’ That nationalism was framed by two indisputable facts:

- Algerian wine flooded into France, satiating domestic demand when supply didn’t exist.

- Algeria was governed from 1848, through its independence in 1962, in a dual-natured manner. The coastal regions were treated as a part of France proper, like the Mediterranean island of Corsica. The desert interior was looked after like its other overseas possessions.

When the need was there, France heavily promoted wine production in Algeria. Tensions quickly surfaced, however, as production in ‘domestic’ France recovered by the turn of the century. The combination of restored French harvests and the new Algerian wines led to massive price declines. Farmers who hadn’t fled to Algeria, having revived their vines, were unable to sell their wines at a profit. The ensuing tensions manifested themselves in two ways:

- Street protests and violent riots broke out, led by disgruntled farmers, particularly those from lower quality regions that produced relatively cheap table wine.

- Organizations of producers from prestigious regions like Bordeaux, Burgundy and Champagne lobbied the French government to introduce quality regulations, the primary demand being clearly labeling exactly where the wine in a given bottle had been grown.

Events finally came to a head in the summer of 1905. In July of that year, the French Governor General of Algeria, Charles Jonnart, acting with a British Partner James Leaky, offered 50,000 hectoliters of Algerian wine for sale in London. The advertisement declared the product French, as “Algeria is now an integral part of France.” French wine producers were enraged. A month later a law was introduced, requiring French wine labels to state their region of origin. Those regional boundaries were drawn up over the next seven years. Referred to as appellations, they were codified into the modern AOC system in 1935.

Labeling laws might have made it clear where French wine was grown, but they seemingly did little to choke off Algerian production. A brush with Phylloxera and WWI did knock Algerian production down to 5 million hectoliters in 1922, but output climbed back to 20 million hectoliters by 1935. More laws were introduced in the intervening years, at the behest of lobbying by French winemakers, dictating yield and production limits, bans on planting new vines, and other restrictive measures. These laws, and WWII, finally made a dent. Algerian production declined, though not nearly as much as French winemakers would have liked. In 1961, a year before France ceded control of Algeria, the newly independent country would have been the 4th largest producer of wine in the world, trailing only France, Italy and Spain. For all the efforts by French winemakers (and we’ve only summarized them), it was the country’s new independence that produced the two nails in the coffin of Algerian wine production – which stood at 15 million hectoliters at independence. That said, the French did do their best to hammer in one of those nails.

The Collapse

The new Algerian government nationalized the wine industry. Vineyards were handed off to local politicians to run, men who knew little about farming or wine production. While production didn’t completely collapse in the face of this lack of knowledge, the second reason for the decline made remedying this skill gap a pointless exercise. Despite decades of soaring wine production in Algeria, a local market never developed, as the non-French population were then and are now Muslims whose religion prohibits the consumption of alcohol. The European immigrants in Algeria, who did consume the local wine, fled the newly independent country, drying up the only source of local demand. Algeria exported virtually all of the wine it produced. And prior to independence the vast majority of that wine went to France, for consumption and for blending.

Following independence, the French government promised to continue purchases over a number of years, on a large scale, but under domestic pressure, those promises were never met. Further, the French government banned all non-French wine from being used in blends, a regulation adopted throughout the rest of Europe in 1970. Looking for an export market, a year earlier the Algerian government had turned to the Soviet Union. The nations hammered out a massive seven-year contract – for 5 million hectoliters of wine annually – but the price was too cheap for Algerian winemakers to eke out a profit. With no profitable export markets remaining, production collapsed. In 1962, Algeria produced 15 million hectoliters of wine, and exported 14.8 million of that. Production came in at 600,000 hectoliters in 2008. The year before exports were measured at 18,000 hectoliters. To all but a few a few of the world’s drinkers, Algeria, once the world’s greatest wine exporter, is today a source of trivia.

If you want to learn about the wine being produced in Algeria today, visit the ONCV, which controls much of the nation’s modern industry.

Source: The Rise and Fall of the World’s Largest Wine Exporter (And Its Institutional Legacy), Giulia Meloni and Johan Swinnen (Warning PDF!)

Images via Shutterstock.com