If being single, and dating in general, is some kind of jungle blood sport (and it is) then singles bars are the cages we all temporarily surrender ourselves to—ideally for the purposes of speeding up/entirely avoiding the thrill of the “chase.” Sure, your friend Amy met her husband when they both went for the same bag of gluten-free granola at a farmers market and just couldn’t stop giggling. But generally speaking, reaching for the same nutritionally trendy cereal items, or bumping into someone and dropping all of your books in a hilarious-but-charming way doesn’t tend to yield nuptials. These days it would probably yield an adorable lawsuit, because people are crazy.

Hence, the singles bar. A bit of a conceptual dinosaur, but an intriguing one, the three-dimensional precursor to the digital singles bar that is the online dating site. Most able-bodied singles don’t run to a designated singles bar—any boozed up establishment is fair game for romantic catch-as-catch-can. But we owe the basic concept of the tipsy public mingle to a pretty weird and unlikely forefather, quite possibly the last place genuinely ambitious singles would find themselves on a Friday night: T.G.I. Friday’s. Also known as the first “fern bar.” But we’ll get to that.

First, good to know, we have at least two things to blame for the emergence of T.G.I. Friday’s: Prohibition, which basically bifurcated the male-female drinking culture (gals you’d bring home to mom weren’t likely to frequent speakeasies, and tended to drink at home); and the seemingly insatiable romantic ambitions of a perfume salesman named Alan Stillman. Presumably, despite spritzing perfume on the wrists and necks of ladies for a living, the essential oils expert wasn’t happy with his ability to meet girls. And as he told Aaron Goldfarb, “It wasn’t easy to meet women and get into bed with them. Believe me, it wasn’t easy for women either.”

And this despite the fact that the Upper East Side in the ‘60s was apparently a font of estrogen, often in the form of models and stewardesses (there was a building on East 65th affectionately/creepily referred to as the “Stew Zoo.”) A resident of the UES, Stillman found his way to those women the way most did in those days: cocktail parties. As he told The New Yorker’s Nicola Twilley, “What would happen is that, on Wednesday and Thursday, you’d start collecting information—things like, ‘On Friday night at eight o’clock at 415 East Sixty-third Street, there’s going to be a great party run by three airline stewardesses. You built up a cocktail list and you bounced from one place to the other.”

Maybe the search for invites, or the hop from block to block, exhausted Stillman? Or maybe he just saw a more efficient way. Either way, there came a day where he knew he wanted to go to a bar, a single designated destination, and be able to expect the company of a variety of single women. A creepy but creative 1960s version of “If you build it, they will come.”

Which shouldn’t suggest single women around New York City were just waiting for some perfume salesman’s invitation to descend upon the ranks of single men*. But bars at the time were still catering largely to the guys, a holdover from Prohibition. Harsh drinks, secret code words, matters of honor and the ability to run from the fuzz in heels (probably?) factored in most womens’ choice to stir up some Martinis, and find revelry in the predictable comforts of a cocktail party.

According to Boston.com, “Before T.G.I. Friday’s,” Stillman said, “four single twenty-five year-old girls were not going out on Friday nights, in public and with each other, to have a good time.” Stillman knew he could draw out the crowds, but needed capital, so he borrowed the money—just $5K at the time—from his mom. And likely never repeated that fact to any of the singles he’d end up meeting.

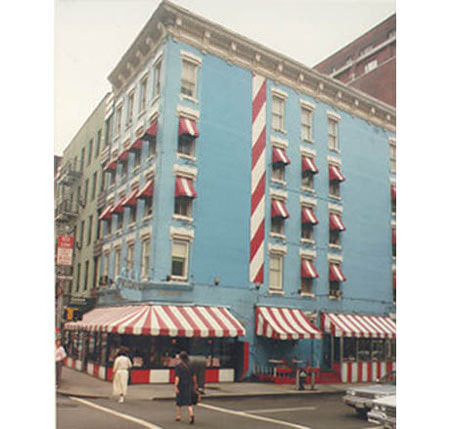

Instead of opening a new place, Stillman refurbished an East Side spot called Good Tavern, “feminizing” it with homey décor, including the ferns that would come to designate this kind of establishment. He also painted it light blue, because apparently any darker colors would terrify women of good repute, chucked those now famous red and white stripes on the awning, and added a few Tiffany lamps—because in 1965 as today, you want to see the person you’re canoodling with, but not too well.

It seems a weird name to us nowadays, but the fact that Stillman named the place T.G.I. Friday’s makes a ton of sense: he’d never been quite shy about his eagerness to reach the drinking festivities of the weekend. And surprise, it was an instant hit, with lines meandering down the block and imitators opening on the same block in less than two years. Even if the era of the singles bar is basically over, Stillman thinks it might have given birth to all the other iterations of nightlife matchmaking we’ve seen since, calling T.G.I. Friday’s, “the first line in the history of bars, restaurants, and discos.”

He sold in the 1970s—and would go on to open Smith & Wollensky’s—which is why the vibe of modern T.G.I. Friday’s has less flirtation than obligatory flair. But in an era where a possible romantic connection can be dismissed by the power of an aggressive leftward thumb-swipe, there’s something honest, and a bit more earnest, about the tacky, glitzy, face-to-face awkwardness of the singles bar.

*Important to note: Stillman was looking for a way to coax single women into the social scene, but that doesn’t imply that the high bar tabs and social indignities of bar-side mid 20th Century courtship were relegated to heterosexuals; alas, nobody escapes, to this day.