Three barrels found along the River Vesle in France have quickly taught researchers about ancient barrel production.

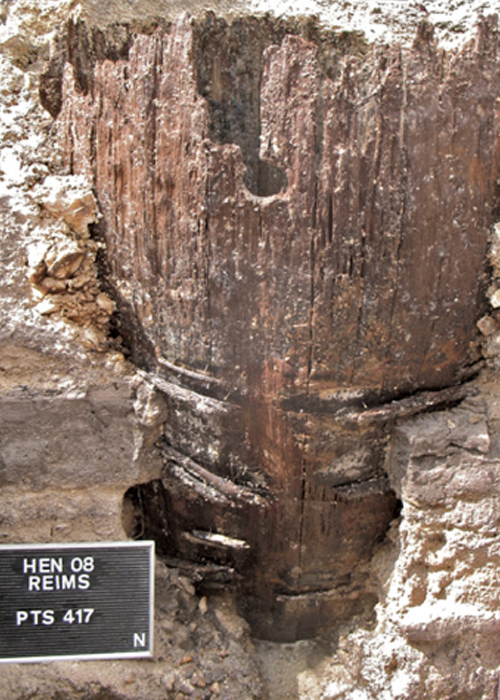

A team of archaeologists working in Reims (the largest city in the Champagne region) first uncovered the barrels in 2008 and traced them back to somewhere between 100 – 400 AD, according to The Drinks Business. The team emphasized that the barrels were found in an “outstanding state of preservation,” which allowed them to easily identify how and why they were produced.

While the barrels were believed to have served as water butts at the end of their lives, they were also clearly used in the wine trade for years before. Part of this was shown in remains of malic and tartaric acids, which are often left behind by alcohol fermentation. However, a series of 45 identification marks on the barrels allowed the team to dive even deeper.

Each mark signified a step in the barrel making process, researchers believe, as well as the route the barrel took once completed. The marks are unique and specific to the different craftsmen who shared a role in producing the barrel, and were added at different points from creating the staves to assembling the final product.

Further along, the wine merchant who owned the barrels then marked them before sending them to the wine supplier who was required to brand the barrels after they were filled. At times, these stamps indicated the type of wine included and differentiated barrels sent to the army, tavern keepers, and merchants.

In reading through these markings the team eventually concluded, “that many different agents in the wine sector were involved. This network brings together winegrowers, craftsmen, merchants, sponsors, transporters and sworn agents in circulations of remarkable geographical, provincial and economic scope.”

Even the barrel’s materials were sourced from around the continent, with European silver fir used for the staves, hazelnut saplings for the hoops, and a species of Mediterranean grass found to fasten the barrels together.

Given the organic nature of these materials, it’s amazing they were unearthed in such immaculate condition. Perhaps best of all (for those who live in the Champagne region at least), the remains are now on show at an exhibition in Reims that’s being funded by Champagne Taittinger.