Whether you end your day with an ice cold Corona or reach for a bourbon barrel-aged stout, if you’ve cracked a beer anytime in the last several years, you’ve probably noticed a surge in the number of alternatives to macrobrews—those big commercial brewery beers like Corona, Bud, Miller Lite, etc.

These alternatives make up a category called “craft beer.” And while it’s easy to spot the difference between Miller High Life and Dogfish Head Raison D’Etre, defining craft beer generally is a murkier (frothier?) business.

American (Beer) History

The story of craft beer is the story of America’s broken love affair with suds. As we’ve discussed[link to History of Beer], brewing is an age-old art, and actually came to this country before, well, independence, with record of the first known brewery in New Amsterdam (aka NYC) in 1612. (Of course Native Americans were not only here first, they were fermenting first, in this case an early alcoholic beverage made from corn.)

As agriculture and later industrialization took hold of the young nation, so too did a love of beer and brewing. The nineteenth century saw huge growth in the number of American breweries, not to mention an influx of immigrants and other beer styles (including the German import, lager) which took an especially strong foothold). And while there was some evidence of consolidation—small breweries being absorbed into bigger ones—brewing was still a diversified industry in the nineteenth century.

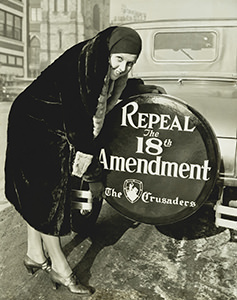

But by 1920, a little thing called the Temperance Movement had mutated into the great, big, federally-mandated monster known as Prohibition. And while alcohol didn’t quite disappear during that time, small American breweries took a major hit. Nor did they entirely recover when Prohibition was repealed in 1933: industrialization saw even more rapid consolidation of breweries, all while lighter lager emerged as the dominant style. Brewery numbers shrinking, light lager appeal growing—bad news for variety in American beer.

But by 1920, a little thing called the Temperance Movement had mutated into the great, big, federally-mandated monster known as Prohibition. And while alcohol didn’t quite disappear during that time, small American breweries took a major hit. Nor did they entirely recover when Prohibition was repealed in 1933: industrialization saw even more rapid consolidation of breweries, all while lighter lager emerged as the dominant style. Brewery numbers shrinking, light lager appeal growing—bad news for variety in American beer.

But then a funny thing happened. With only 45 independent breweries left in 1978 (89 total breweries), a small but enterprising group of homebrewers started brewing beer themselves, reviving styles that were no longer widely available. See, by that point, due to increases in travel and a couple World Wars, Americans had been introduced to the still robust beer drinking cultures of Europe. But when they got home, beer drinking options were extremely limited. Homebrewing – legalized by Congress in 1978 – was the answer.

From Home to Craft Brewing, or Sierra and Sam

Of course, given the revelatory deliciousness of well-made beer, the leap from home to professional “craft” brewing didn’t take long. And while folks like Fritz Maytag took over Anchor Brewing in 1965 and intrepid homebrewer Jack McAuliffe opened what is sometimes called the “first microbrewery” in 1976, the two men most commonly associated with the foundations of the craft industry are Jim Koch and Ken Grossman, aka Sam and Sierra.

Yes, Sam Adams and Sierra Nevada really are two of the pillars of the craft industry. Bear with us… See, in 1978, when there were only those 45 aforementioned independent breweries, an innovative college dropout named Ken Grossman borrowed some money from friends and family to co-found the (then) 10-barrel brewery he called Sierra Nevada. Success, growth, and three decades later, you see Sierra Nevada Pale Ale in almost every refrigerated case of beer. But that doesn’t mean Sierra didn’t begin—or continue—as a craft brewery (basically, a smaller-output brewery that puts quality ahead of quantity, but we’ll get to definitions in a minute).

Yes, Sam Adams and Sierra Nevada really are two of the pillars of the craft industry. Bear with us… See, in 1978, when there were only those 45 aforementioned independent breweries, an innovative college dropout named Ken Grossman borrowed some money from friends and family to co-found the (then) 10-barrel brewery he called Sierra Nevada. Success, growth, and three decades later, you see Sierra Nevada Pale Ale in almost every refrigerated case of beer. But that doesn’t mean Sierra didn’t begin—or continue—as a craft brewery (basically, a smaller-output brewery that puts quality ahead of quantity, but we’ll get to definitions in a minute).

The same story (roughly) goes for Sam Adams (The Boston Beer Company). Jim Koch was a beer lover who, like Grossman, wanted to change what beer was available to the public, so he founded The Boston Beer Company, brewed a recipe of his great-great-grandfather’s that he called “Samuel Adams Boston Lager,” and hasn’t looked back. Again, like Sierra, Sam Adams might not seem very “craft” at this point, given its massive presence in the beer world and generally set roster of styles, but compared to the big guys, Sam is still relatively craft—4.1 million barrels in 2014.

Small, Independent, Traditional (Oh My!)

We know what you’re thinking. Can 4.1 million barrel output really be “craft”? Well, yes, though the answer’s a bit more complicated. And that’s because defining craft beer is hard to do. Even the craft beer advocacy group, the Brewers Association doesn’t define it, but “rather leaves [that] to the beer enthusiast”—meaning you could down a can of Coors Light, crush it against your forehead, and declare it the most delicious, nuanced “craft beer” you’d ever tasted.

“Craft Brewer,” on the other hand, is a term that can earn a brewery certain rights, marketing cachet, and even tax breaks, so defining what qualifies as a craft brewery is pretty essential. And that’s what the Brewers Association does, with three words: small, independent, and traditional.

Of course, what these words refer to has actually changed over time, and for good reason: the craft industry is growing. But let’s take a look:

- Small, for instance, used to mean a production output limited to 2 million barrels per year. By 2014, it was 6 million. And in their update, the BA added an alternative percentage measure—basically a “craft brewery” could only produce 3% of the market, meaning if the market output grows, a craft brewery can grow right along with it.

- Independent means basically the same thing—only 25% of a brewery can be owned by anyone not identified as a craft brewer.

- But traditional definitely changed in 2014, with the BA now defining it has having a “majority of its total beverage alcohol volume in beers whose flavor derives from traditional or innovative brewing ingredients in their fermentation.”

That last change is pretty huge, because it means not only malt but adjuncts (like rice, corn, etc., generally associated with cheap filler used by big bad macro beer companies) can be included in the ingredients of the malt bill that influence the flavor of a craft beer. This is why Yuengling now qualifies as a craft brewery—it also gives the BA access to Yuengling’s bigger budget, which it may use to fight the good fight against macro beers as fights over market shares continue. Of course, the BA has its own non-financial rationalization for allowing adjunct grains into the new definition of craft brewing: “The idea that brewers who had been in business for generations did not qualify as ‘traditional’ simply did not cohere for many members [of the Brewers Association]. Brewers have long brewed with what has been available to them.”

The question is, when does a craft brewery stop being craft?

The question is, when does a craft brewery stop being craft?

The basic issue is growth. And Boston Beer and Sierra Nevada are perfect examples: self-styled craft breweries that found success and grew, paving the way for the myriad craft breweries that followed (there were 3,464 independent breweries in 2014). But now that the market’s teeming with scores of local, idiosyncratic craft breweries, Boston Beer and Sierra seem closer to big business. Which, in a way, they are—because they’ve succeeded. Growth is the goal of most business, including craft. Even the BA wants to take craft beer’s share of the market to 20% by 2020. The question is, when does a craft brewery stop being craft?

Well, Congress may soon have something to say about it. A bill by Oregon Senator Ron Wyden proposes amending the definitions of breweries according to three levels of annual output: 2 million, 6 million, and anything above that. Those in the lowest and middle category would get the tax breaks afforded to craft breweries (the government levies a federal beer excise tax, at a lower rate for smaller breweries). Those in the highest category—which the Boston Beer Company is fast approaching at 20% annual growth—would get no tax breaks, basically equating it with the macro breweries it was founded to compete against.

Confusing, yes. But the basic story is there’s more beer to be had, a good problem. Whether you call a bottle of great, great grandfather Koch’s Boston Lager “craft,” well, that’s still up to you.