Malted barley is one of the most important ingredients in whiskey, used for nearly every style in the world from bourbon and rye to — of course — single malt. A millennia-old process, malting unlocks enzymes that make barley more easily fermentable, and that assist in converting the starches of other grains to sugar. Essentially, malting makes the grain — which is almost always barley, though other grains can also be malted — believe it’s been planted in the ground, preparing to grow. It gets steeped in water, then left to dry and germinate to the point of sprouting, at which point growth is sharply stopped with heat.

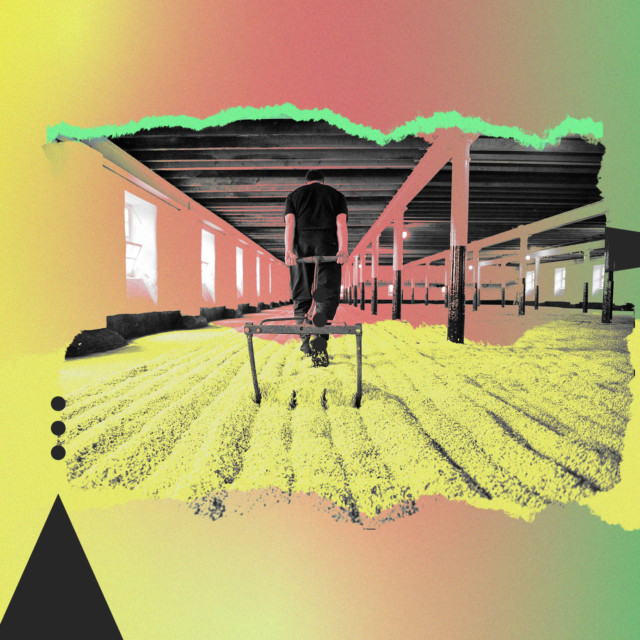

Until the 20th century, malting was a hands-on endeavor, usually requiring a large floor for the germination process, many workers to regularly rake the grains to prevent rot and tangled roots, and a kiln for drying. The labor was backbreaking, with workers often suffering a repetitive strain injury called “monkey shoulder.” After industrialization entered the process widely by the mid-20th century, many distilleries closed their on-site maltings.

These days, commercial malting facilities supply just about every whiskey brand in the world. But a few distillers continue to make their own malt, insistent that it’s worth the effort. “It’s about tradition,” says Simon Brooking, senior ambassador for the Laphroaig and Bowmore distilleries, which both still use malting floors. “And so much of whisky making is about the passing on of tradition.”

Other Scottish distilleries with their own maltings include Balvenie, Highland Park, Springbank, Kilchoman, Benriach, and Glen Garioch, which recently revived its malting floor after nearly three decades of disuse. Distillery manager Kwanele Mdluli says the move not only strengthens Glen Garioch’s historic roots, but gives it another way to differentiate itself, especially as the restored maltings will allow the distillery to make peated whisky for the first time since the 1990s.

Apart from Springbank, none of these distilleries malt all of the barley they need. The proportion ranges from a percent or two of total supply up to 30 percent at the likes of Bowmore and Kilchoman. But malting allows these producers to showcase unique variations on their house styles, such as Kilchoman’s annual 100 percent Islay release and Benriach’s Malting Season, which debuted last fall. “There would’ve been no point in doing this if the [floor-malted] whisky we tasted was the same as the whisky we tasted from the commercial malts that we use,” says Stewart Buchanan, global brand ambassador and former production manager at Benriach in 2012, when the distillery brought its floor maltings back online. “It’s drier, more nutty, not as sweet or fruit-forward [as typical Benriach].”

New World, Old Process

A handful of distilleries outside of Scotland, like Japan’s Chichibu, Bimber in London, Denmark’s Stauning, and Domaine des Hautes Glaces in France, also have malting floors. In the U.S., several craft distillers have adopted the process, too, among them Coppersea and Hillrock Estate in New York, Virginia’s Copper Fox, Maine Craft Distilling, Bently Heritage Estate in Nevada, and Arizona’s Whiskey Del Bac. The Tucson distillery opened in 2011 as a single- malt producer, offering unsmoked and mesquite-smoked expressions, all made on its own malting floor.

“I was not making very good malt at all [early on],” says Del Bac co-founder Stephen Paul. “But it was good enough to move the project along.” He explains that it was necessary to malt in house because there was no mesquite-smoked malt available commercially at the time, “and I didn’t want to call up a malt house and give away the idea at that point.” Del Bac has since grown and now uses a custom germination and kilning tank for its smoked malt, while buying its unsmoked malt from commercial sources.

In Denver, Leopold Bros. Distillery opened its first malting floor in 2015. Co-founder and head distiller Todd Leopold says that there were a couple of reasons to malt its own barley: First, it has access to the same locally grown, high-quality grain used by brewing giant Coors. Second, it actually ends up being cheaper for Leopold Bros. to make its own malt than to purchase it from elsewhere.

“It’s relatively inexpensive because the volume infrastructure [of local agriculture] is built up,” Leopold explains. Originally educated as a brewer, he has extensive training in malting that informs the way Leopold Bros. handles its grain. The distillery opened a new malt house in 2020, capable of malting 22,000 tons of barley at a time. The two-story design makes the most of a small footprint and includes a bucket elevator that moves the malt up a level as it’s germinating, which helps with temperature control and other issues. The malt house supplies all of the distillery’s needs, and even yields enough to sell to local breweries, like New Belgium, for use in specialty beers.

Flavor First

Leopold Bros. aside, malting in house is expensive and labor intensive, and it tends to produce more variation than industrial methods. “Every batch is different depending on the weather, depending on the temperature of the floor — all these things will play a factor in how that germination reacts or starts its process,” says Benriach’s Buchanan, explaining that milling and mashing are impacted by such variability. “It’s something you have to be on top of all the time. … There’s just more mollycoddling of [the malt] through the production.”

But for both Scottish and American distillers, the benefits of in-house malting are worth it. For one, they get total control over the process. Frey Ranch Distillery in Fallon, Nev., farms all of its own grains and contains the entire whiskey-making process — literally from grain to bottle — on site. “To make a truly 100 percent grown-by-us product, we have to malt our own barley, which is a giant pain in the ass,” says co-founder Colby Frey. “It’d be easier for us just to buy the malt — cheaper — but that’s not who we are.” Frey custom built his own malting drum, which is primarily used for barley but at times also used for corn, wheat, and rye, as well as a silo smoker to impart additional flavors.

The whiskeys made from the malted grains, including a “quad malt” bourbon, are still maturing, but Frey says that in general they are sweeter than their unmalted counterparts. That’s the second major benefit of DIY malting: flavor. It’s especially noticeable if the malt is dried over smoke. Laphroaig’s signature iodine and Band-Aid notes, for example, come directly from its cold-smoked house malt, made with peat that’s cut by hand just a stone’s throw from the distillery. “It’s a fingerprint,” Brooking says. Other distilleries that use their own peat for kilning display unique flavor signatures, too.

At Del Bac, Paul designed the “mesquited” malt specifically to evoke the Sonoran Desert and the common aroma of mesquite that pervades festivals, campfires, and home grills. “I grew up in the desert and have a very profound love of this place,” he says. “It grew out of a sense of place. That’s why we’re here.”

Now that it has two kilns, Leopold Bros. is planning to eventually devote one to Colorado peat-smoked malt. But at the moment, the distillery produces only unsmoked varieties, with Leopold pinpointing richer, more biscuity flavors and aromas through the kilning temperatures, giving him more control over how the eventual whiskey tastes. “I’m chasing flavor first and specs second,” he says. “Our malt whiskey program is based around us making three different types of malts, aging all of them separately, using different yeast, using different barrels. And then at the end of it in 10 years, I can either sell them by themselves or I have a nice way to blend and have fun.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!