Wine regions are like onions. Peel back the outer layer that represents the region as a whole, and you expose its subregions — Burgundy, for example, pares away into the Cote d’Or, Cote Chalonnaise, and Maconnais. Beneath this layer lie smaller communes, such as the Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits. Within communes are village appellations, which house classified vineyards — a.k.a. the onion’s core.

With each layer, we approach the heart, the concept of terroir — a unique combination of soil, topography, and climate that makes every wine individual and unreplicable. Of course, in cases like Burgundy (and almost all Old World regions), the deeper you go, the pricier the wine gets.

A contrarian example is Argentina, a New World region known for its fruity and easy-drinking, if sometimes unremarkable, Malbecs. Its production hub of Mendoza is a complex, concentrically layered region hidden in plain sight. Within the vast region’s five remarkably different sub-regions lies the Valle de Uco (Uco Valley), the high-altitude home of the nation’s best Malbec production.

A growing number of winemakers there, such as Sebastián Zuccardi and Edgardo del Popolo, among many others, are proving that world-class terroir — the core of the onion — exists in the Uco Valley. They’re doing this by establishing new appellations known as Geographical Indications (GIs), which in turn serve as shorthand for consumers to easily identify some of the best- quality Argentine wines that might go otherwise unnoticed.

For del Popolo, who works across the majority of the Uco Valley’s GIs in his roles as CEO and general manager at Susana Balbo Wines and co-owner of the boutique project PerSe, the importance cannot be overstated.

“As producers, we have to take this opportunity — given to us by regional diversity — to attract consumers and help them understand that Argentina is about much more than just ‘Malbec,’” he says.

Zuccardi agrees. “When you talk about [Malbec], you are talking about a commodity — something that you can plant in every place in the world,” he says. “But when you talk about the place, this is something that is unique.”

The Diversity of the Uco Valley

Among the Uco Valley’s complexities are its variations in altitude, temperature, soil, and sunlight. The area is approximately 45 miles long and 15 miles wide, with roughly 70,000 acres of cultivated vineyards within it — the latter a near-identical figure to Burgundy.

Zuccardi refers to the Uco Valley’s product as “mountain wine.” But, he adds, “just talking about the Uco Valley is not enough because of the difference in altitudes and the variation of soils that we have.”

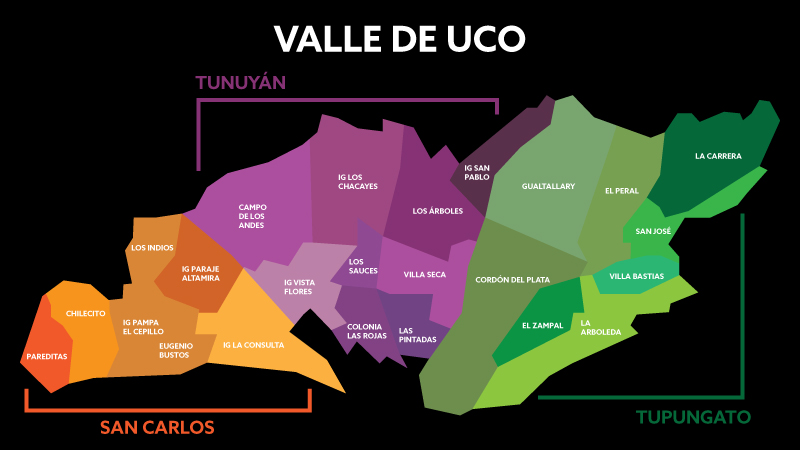

The Uco Valley is geographically split into three departments — Tupungato, Tunuyán, and San Carlos, each divided by the rivers Las Tunas and Tunuyán. Tupungato, the northernmost of the three, ranges in altitude from around 1,600 meters above sea level at its highest point (where it’s closest to the Andes) to around 850 at its lowest (in the east). Tunuyan and San Carlos experience similar, though not quite as extreme, altitude variations.

“This gives you a lot of variability in terms of weather,” Zuccardi says, referencing the temperature differences and varying sunlight intensities. These factors influence the ripening period for grapes and the optimal point at which they should be harvested.

While the entire region is planted on alluvial soils, a blend comprised of a combination of clay, silt, sand, and gravel deposited over many years by running water, compositions vary dramatically across the three departments.

With such impactful geographic and climatic variations, it seems farcical that, when recognized at all, the Uco Valley continues to be viewed as just one cog within the Argentine Malbec machine. The absurdity of this idea is compounded when compared to obsessed-over Burgundy — not in terms of quality or prestige, which Burgundy wins, but in pure numerical and scientific terms. Both account for roughly the same area of cultivated vines, though one is microscopically analyzed at vineyard level, while the other is often viewed as a homogenous mass.

Putting GI on the Map

In 2008, Familia Zuccardi, along with bodegas (wineries) Chandon and Catena Zapata, sought to have the Uco Valley’s Altamira district recognized as a standalone appellation by the country’s National Institute of Viticulture (INV).

Located within the San Carlos department, the southernmost within the Uco Valley, the Altamira district was already home to 100-year-old vines and some of the most varied soils within the valley. The bodegas commissioned the National University of Cuyo to research the soils and climate, and produce satellite mapping to demarcate a new GI.

In 2013, after five years of research, the INV approved the 3,500-acre GI, officially recognizing it as La Indicación Geográfica (IG) Paraje Altamira, or IG Paraje Altamira.

“We have been working with great scientists and professors in edaphology [a branch of soil science] and have been able to learn and share research that forms an important base for the future of Argentine wine,” Luis Reginato, Catena Zapata’s head of viticulture, said in an interview.

The process proved to be forward-thinking: Multiple districts within the Uco Valley have since been granted GI status following the extensive work and research of local bodegas. These include La Consulta and Pampa El Cepillo, also located within San Carlos; and Los Chacayes and San Pablo in Tunuyan. Two of the four, Pampa El Cepillo and San Pablo, were granted GI status this year.

Many other applications are in the pipeline, most notably Gaultallery in Tupungato. Although domestic (Argentinian) consumers have been enthusiastic about the developments, del Popolo says, “It’s been a learning curve for all. As producers, we’ve learned to give more importance to soils and to divide regions, which we might not have done in decades gone by.” Meanwhile, the next challenge is communicating that message to international markets.

“Many times I’m asked: ‘What is coming after Malbec in Argentina?’” Zuccardi says. “The answer is more Malbec, but communicated in different ways.”

Five Uco Valley Winemakers to Try

While terroir-driven bottles from Old World regions such as Burgundy are prohibitive at best, geographically specific Malbecs from the Uco Valley are widely available on the market. They’re a slight upgrade from mainstream Malbec, but many retail for around $25 in the U.S., providing an affordable intro to the concept of terroir and a glimpse at the future of Argentine winemaking.

Altos Las Hormigas

Altos Las Hormigas makes terroir-driven wines by practicing minimal-extraction vinification; using neutral oak and natural yeast; and adding very little sulfites. Look out for its “Appellation” series of Malbecs (Gualtallary, Paraje Altamira, Vista Flores). Average price: $40.

Bodega TeHo

Co-owners and co-winemakers Alejandro “Colo” Sejanovich and Jeff Mausbach offer two stunning expressions of the Altamira GI in the form of their “TeHo” and “ZaHa” Malbecs. Average price: $35.

Catena Zapata

With over 100 years of winemaking experience in Mendoza, the Catena family played a pioneering role in developing high-altitude winemaking in the Uco Valley. Like Altos Las Hormigas, this bodega also offers an “Appellation” series of Malbecs, with its Uco Valley bottlings arriving from La Consulta, Paraje Altamira, and Vista Flores. Average price: $20.

Familia Zuccardi

Familia Zuccardi offers a wide range of Malbecs designed to highlight the unique location in which the grapes were grown. The Poligonos line, comprising the Tupungato Alto Malbec (from Gualtallary), Paraje Altamira Malbec, and San Pablo Malbec, is vinified in concrete tanks to allow the purest expression of fruit and place. Average price: $25.

Michelini Brothers

The Michelini name is fast becoming synonymous with terroir in the Uco Valley, with brothers Gerardo, Juan Pablo, and Matias offering a range of geographically specific wines through multiple projects across Gualtallary. Seek out any of the Malbecs from their SuperUco and Zorzal wineries. Average Price: $15-$35.