Walking around Manhattan, it’s hard not to notice the island’s deep and rich history. Patinated monuments to famous national heroes, cobblestoned streets — simultaneously delighting sightseers and aggravating cab drivers — and, of course, the architecture, especially as one heads toward the southern tip of Manhattan, the oldest part of New York City.

St. Paul’s Chapel in Lower Manhattan dates back to 1766, and George Washington prayed there after being inaugurated as the first president of the United States just down the road at Federal Hall. Bowling Green is the city’s oldest park, and was even the site where the Dutch “bought” Manhattan from the Lenape in 1626.

These sites and more have made the area a top destination for tourists and history buffs alike, and plenty of businesses have sought to capitalize off this by claiming to be the oldest this and the oldest that. Of interest to me — and to VinePair readers as well — may be the bars claiming to be “New York’s oldest.”

So I sought to find out, once and for all, what truly is the oldest bar in Manhattan.

After many selfless pints, all in the name of epistemological truth and journalistic duty, I’ve narrowed it down to three drinking establishments — which rise above the rest as the oldest and most historic spots on the island.

Fraunces Tavern (1762)

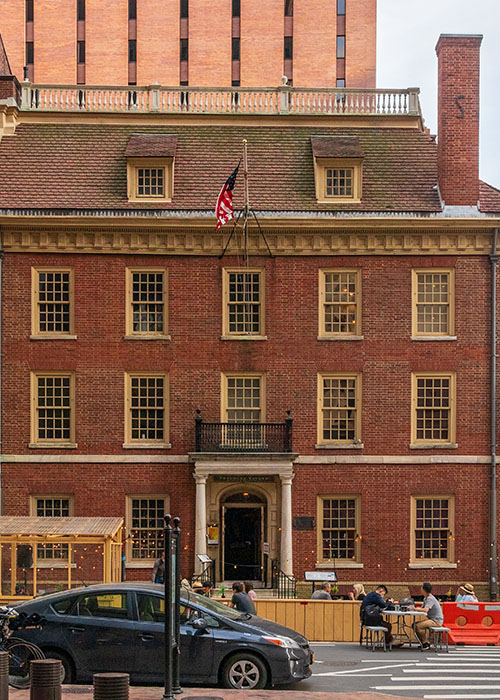

Located at the corner of Pearl Street and Broad Street at the southern tip of Manhattan, just a couple blocks away from New York Harbor, is Fraunces Tavern. Surrounded by streets with other plain, utilitarian names like Water Street, Bridge Street, and Stone Street, the tavern harkens back to a simpler time. It looks like a four-story colonial mansion; half of its facade is made up of red brick, while another wall is composed of yellower brick, closer to gold.

Inside are many gorgeously ornate rooms covered in rich, dark woods illuminated by warm lighting, arranged in a wonderfully asymmetrical warren of nooks and crannies that you only see in older buildings, complete with a whiskey bar, piano bar, and even a formal dining room for private events.

The tavern’s website claims that it is “the oldest and most historic bar in the city.” And it is quite old.

Its name comes from Samuel Fraunces, who opened the tavern in 1762 — although the building itself was erected even earlier, in 1719. Its early years are also its most famous, as the tavern played a notable role during America’s Revolutionary period.

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1776, the New York Provincial Congress hosted a banquet for General George Washington and his staff. According to the tavern’s museum website, the final bill came out to 91 pounds for “78 bottles of Madeira, 30 bottles of port, and sixteen shillings for ‘wine glasses broken.’”

Sounds like a good night!

Then, in perhaps the tavern’s most famous episode, Washington returned again at the very end of the war in 1783 to bid his army an emotional farewell before retiring to Mount Vernon, Va.

Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge wrote about the farewell in his 1830 memoir:

“[Washington’s] emotions were too strong to be concealed, which seemed to be reciprocated by every officer present. … Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.”

How many bars can claim to have hosted such an emotionally charged evening? George Washington in tears? C’mon.

After the war, Fraunces leased the tavern to the fledgling government, and it became office space for the newly formed Departments of War, Foreign Affairs, and the Treasury. For the next century or so, the tavern changed hands many times, and endured three damaging fires that left the building almost unrecognizable by 1900.

On the brink of demolition, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Sons of the American Revolution, and the City of New York got involved to save the building. The Sons of the American Revolution ended up with the property and undertook an extensive renovation to restore it to its colonial aesthetic.

The only problem: No 18th-century images existed of Fraunces Tavern.

“We just don’t know what it looked like,” explains local historian Thomas Silk, who runs the popular Instagram account @landmarksofny and published “Hidden Landmarks of New York” in 2024. “Make it look like what Washington would have seen was basically the directive.”

And while some purists may knock the tavern down a peg or two for this, I must say: They did a great job. It certainly feels old — with thick, gnarled floorboards, sumptuous leather booths, and oil paintings lining the walls, pointing to the tavern’s revolutionary past.

As for what they’re serving up, the chicken pot pie is a popular entrée, and there’s an extensive selection of American whiskey, Irish whiskey, and Scotch at their Whiskey Bar. They’ve also partnered with Staten Island’s Flagship Brewery to deliver the tavern’s signature draft beers, including the popular nitro stout and red ale.

Also, as America celebrates its 250th anniversary in 2026, Fraunces plans to honor the occasion with some period-appropriate drinks.

“Ales and good punches is what we were known for [in the 1700s]. The one at the moment is called the presidential punch,” says Eddie Travers, who has owned the bar since 2010. “I could tell you the ingredients, but then I’d have to kill you,” he adds with a laugh.

“We just don’t know what it looked like,” explains local historian Thomas Silk, who runs the popular Instagram account @landmarksofny and published “Hidden Landmarks of New York” in 2024. “Make it look like what Washington would have seen was basically the directive.”

Looking around, it’s hard not to feel the import of the place — there’s even a museum upstairs showcasing the building’s important role in American history.

And while it may not be exactly the same as it once was back in Washington’s day, it’s a pretty darn good recreation. Plus, there aren’t too many places left these days where you can grab a beer and a bite in the same spot as the founding fathers once did.

The Ear Inn (1817)

Located at 326 Spring Street, the Ear Inn occupies a quieter stretch of the city. Off the beaten path a bit, it’s a stone’s throw from the Hudson River near the West Village. I went there on a recent cold winter night — the wind howling off the river — which felt appropriate, as the inn has been a respite and refuge for generations of sailors and dockworkers back when this area of Manhattan was a bustling dockyard.

Seascapes, ship etchings, and other seafaring memorabilia — like a ship’s helm and an old-fashioned life preserver — line just about every inch of the inn, even the ceilings, stretching from the well-worn wooden bar to the dining area in the back room, a nod to the bar’s seafaring roots.

The inn calls itself “one of the oldest operating drinking establishments in New York City.”

And it’s true — the spot has been serving drinks in some manner since the early 1800s under many different names, and its history actually extends back to the 1700s, also with ties to George Washington.

The building was first constructed as the home for James Brown, an African American aide to Washington, who is said to be depicted in the famous painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” to the general’s left.

Later on, in the 1800s, a man named Thomas Cooke ran an inn and sold “home beer and crocks of corn whiskey to a constant wave of sailors,” according to the Inn’s website. Even Prohibition did not deter the place from selling alcohol, and it became a speakeasy.

“They used to make beer and whiskey downstairs in the basement,” says Gary Lawler, whose family has owned the Inn since 1977. “We had a big curtain across the front windows. That’s what they did back in the day [to hide from the authorities].”

Perhaps this surreptitiousness is why the bar remained nameless when it officially reopened after Prohibition was repealed in 1933, although locals referred to it as “The Green Door” for obvious reasons.

It wasn’t until 1977, when Lawler’s uncle, Martin Sheridan, bought the place, that it finally became the Ear Inn.

Because of its age and history, the building is a protected New York City-designated landmark, which has strict rules about altering the facade or the classic neon sign outside reading “BAR.”

So Sheridan had to get creative to forge a new identity for the place.

“He painted the ‘B’ to look like an ‘E,’ and it used to be an inn back in the day. So Ear Inn, it made sense,” Lawler explains.

Like many bars in the city these days, the black stuff is the drink of choice for many.

“We can’t keep enough Guinness in the house,” Lawler quips, before noting some of their popular dishes as well. “We’re known for our shepherd’s pie, chicken pot pie, burgers. Our dumplings are very popular as well.”

Not one to argue, I had an order of the dumplings to go along with a pint of Guinness. And while the food and drink certainly hit the spot, the real appeal for me was just soaking in every little detail of this cozy little spot — the perfect balm for a chilly night.

McSorley’s (1854)

Ah, McSorley’s. Where to begin?

Perhaps the most famous of the old-timey bars in Lower Manhattan, McSorley’s Old Ale House stands right in the hubbub of the East Village, across the street from a towering, gleaming building designed by a Pritzker-winning architect as part of Cooper Union.

It’s a stark contrast — and a testament to the Ale House’s stubborn endurance through the ages. It is “New York City’s oldest continuously operating saloon.”

First opened by John McSorley in 1854, the bar originally catered to Irish and German working-class men who made up the neighborhood — and yes, just men; the bar did not allow women until 1970.

From John McSorley onward, only three families have owned the Ale House. The McSorleys sold it to Daniel O’Connell in 1936. O’Connell’s descendants, the Kirwans, sold it to Matthew Maher in 1986. And that’s it. Maher’s daughter, Teresa Maher de la Haba, runs the place to this day.

Perhaps it is this continuity that gives McSorley’s such a unique and quaint feel — it’s remarkable how stable its ownership has been over the years.

There’s still sawdust strewn across the floor, and some of the strangest memorabilia you’ll see: a flounder next to a portrait of Alfred E. Neuman next to a photo of Babe Ruth next to some dusty old wishbones over the bar from some long-deceased fowl.

A naysayer might call it junk, but I love it.

And almost all of these unusual pieces have a story, and thus, there are oh so many stories swirling around McSorley’s.

“The urban legend was that these wishbones were put up there in 1917 by neighborhood boys being shipped off for the First World War,” says Silk. “Then when you could come back, you’d take your wishbone off. So these remaining wishbones are from men who didn’t make it back.”

After some more research, however, Silk concluded that the true reason for the wishbones’ existence was just a past bartender who liked to collect oddities (surprise!).

But where’s the fun in that?

McSorley’s, too, can be connected to a notable president: Another famous tale claims Abraham Lincoln stopped by for a beer at McSorley’s while he was campaigning for president in 1860.

As for the beer, McSorley’s famously only sells a light ale and a dark ale, ferried around by a couple of gruff bartenders who slam down the mugs by the dozen with a satisfying THUD, sending the frothy heads flying about the wooden round tables that line the place.

While it’s hard to tell how good a deal the beer is ($8 for two mugs of ale), given the small size of the mugs coinciding with the sizable heads on the beer (it makes up about half of the glass) — that’s not really the point.

The point is: Abraham Lincoln liked it. So did John Lennon and Woody Guthrie, along with other “Presidents, residents, authors and thieves,” as the Ale House’s website puts it.

“Wishbones were put up there in 1917 by neighborhood boys being shipped off for the First World War. Then when you could come back, you’d take your wishbone off. So these remaining wishbones are from men who didn’t make it back.”

It’s a fun story, so why get caught up in the details?

—

While each of these spots has its own unique and interesting history — each with its own argument or phrasing that allows it to claim that it is the true oldest bar — there isn’t much point in trying to declare one the true winner.

They’re all old, and they’re all great, and I feel lucky that they’ve all survived the centuries, unlike countless other spots that bit the dust — or the wrecking ball, more likely.

So pick whichever one suits you best, grab a drink, and raise a glass to their enduring charm and legacy.