Jugs of beer are universal, surely; but growlers hold a special place in American history (and hearts). In the early 20th century, growlers spoke to star-spangled industry, delivered to laborers alongside lunch pails. Resourceful urbanites whose thirst outpaced their free time purchased beer by the bucket as early as the late 1800s and as late as the 1950s.

It’s easy to associate today’s growlers — typically, glass jugs, brown in color, and 64 or 32 ounces in size — with the rise of craft beer, and our modern era’s infatuation with all things hand-hewn and lumberjack-adjacent. But what has become a ubiquitous method for transporting beer is actually not a new development.

“The history of the growler points to several important things: the diversity of places people have consumed beer in different eras — in the saloon, at home, and at work — and the fact that children and women were involved in using them, even if not always drinking, to the extent that men have,” Theresa McCulla, historian of the American Brewing History Initiative at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, says.

Growler Lore

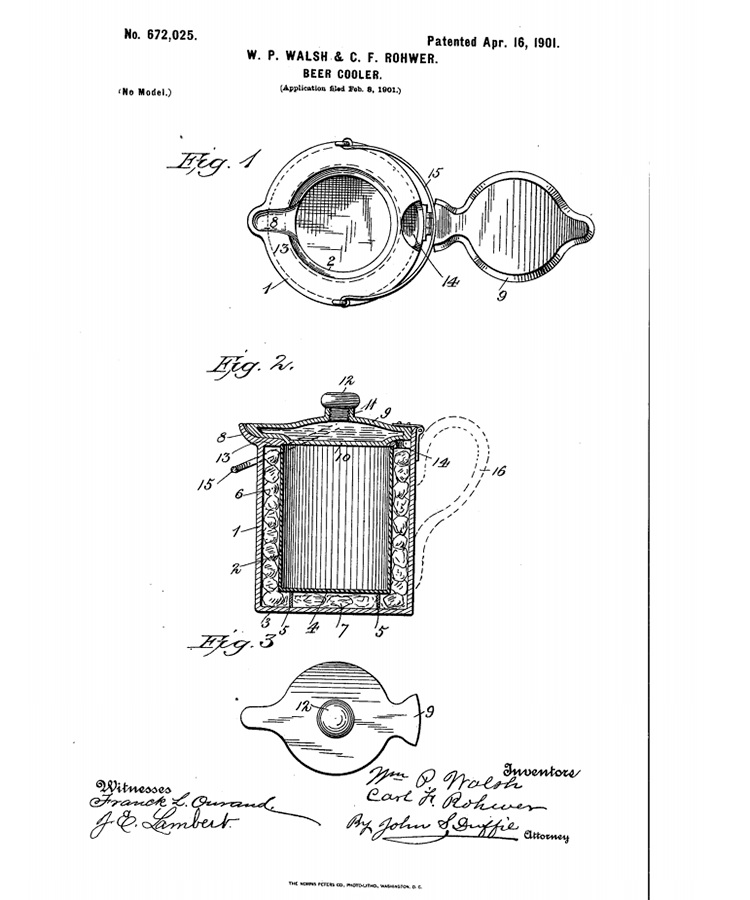

The first patent using the word “growler,” for a “beer cooler,” was registered in the U.S. in 1901. But as early as the 1800s, beer was taken home from local taverns by the pail, often a chore carried out by children.

“Consumers have used growlers to take beer out of where it was produced, whether the brewery or saloon, since the 19th century,” McCulla says. “Consumers would often fill a pail or bucket with beer and take it elsewhere to drink.”

“There does seem to be a history of children and women being sent to the saloon to fill up these containers,” McCulla continues, “and bring them to the place where the fathers or husbands were working, for break in middle of day, or to bring home to be consumed in the home.”

(I can vouch for familial beer distributors — my father, born in 1947, was tasked with bringing beer to his grandmother’s house by the bucket in Brooklyn in the 1950s.)

Rumors abound as to where the word “growler” came from, but the tale told most often is that the lids on these metal pails caused a rumbling sound as they rattled and the carbonation escaped, making a sound akin to a growl. Subsequently, “rushing the growler” and “working the growler” were terms used to describe the errand of retrieving beer from a bar via bucket or growler.

(Another hypothesis, printed in the Trenton Times on June 20, 1883, said, “It is called the growler because it provokes so much trouble in the scramble after beer.” More about that here.)

“To rush the growler … was to take a container to the local bar to buy beer,” Michael Quinion, human encyclopedia of the English language, writes on his now-discontinued website, World Wide Words. “The growler was the container, usually a tin can. Brander Matthews wrote about it in Harper’s Magazine in July 1893: ‘In New York a can brought in filled with beer at a bar-room is called a growler, and the act of sending this can from the private house to the public-house and back is called working the growler’. The job of rushing the growler was often given to children.”

The growler at that time was very much a New York thing, and for some, a deplorable one: Referred to as “low tramps’ slang” with “offensive associations,” the word — and the vessel itself — was believed to be a tool of the depraved. On November 14, 1884, the Atchison Globe allegedly wrote: “I have heard that in New York people of the working-class, who live in tenement-houses, send out a pitcher for beer in the evening. They call it ‘working the growler.’ Here in Chicago the best people indulge in the degrading practice, I regret to say.” The following year, a magazine called Puck wrote: “The old, old story. The happy home, loving parents, the growler, the fall and ruin.”

Along with most things that brought liquid joy in the 1920s, Prohibition threatened to end the growler, but, after a brief interruption, its ubiquity returned after 1933.

By the 1950s and ‘60s, growlers got a modern makeover. Metal pails were swapped for waxed cardboard containers, like Chinese food containers. Soon enough, by the late 1960s, bars were able to sell packaged beer in plastic containers, rendering their metal and cardboard predecessors obsolete. After that, the growler softly grumbled away.

The Birth of the Modern-Day Growler: Grand Teton Brewing

Growlers predate the craft brewing renaissance, but, without one multigenerational microbrewing operation in Wyoming in the 1980s, American drinkers might have never re-embraced these large-format vessels. This time, they took the shape we know it now: half-gallon glass bottles.

As the story goes, Charlie Otto, founder of Grand Teton Brewing, Wyoming’s first modern microbrewery, needed a way to sell his draft beer to go. He used a silkscreen machine to fuse his logo onto half-gallon glass cider jugs to-go, and voila. The modern beer growler was born. Charlie owes this revelation to his father, who suggested the growler at a time when his son didn’t even know what it was.

Flash forward to the post-craft beer nation. Today, growlers are still growlers, used to take beer to go from beer bars, taprooms, and breweries. However, keeping up with the times, what was (and often, still is) a simple glass jug has evolved to more sophisticated devices, in a variety of shapes and sizes.

Some offer promises of temperature control, perfectly preserved carbonation, and freshness for weeks, taking drinkers from taproom to trail to beyond. Brands like Hydroflask give growlers tech-savvy facelifts, with bright-colored, powder-coated, and matte-finished options for the outdoorsy types. DrinkTanks features a stainless steel, double-walled, vacuum-insulated vessel with a serious airtight seal.

“The more recent history of the growler and crowler points to American consumers wanting to share beer with others,” McCulla says. “This is especially true of the craft beer phenomenon, in craft brewing and homebrewing. The growler is so important to both of these strands.”

The crowler, or can-growler, is an offshoot of the growler’s resurgence. Invented by Colorado craft brewer Oskar Blues in 2014, crowlers are particularly appealing to up-and-coming craft brewers with small-scale production. They provide an efficient way to share beer with consumers, “especially those visiting from far away who want to take home beer,” McCulla says. Crowlers enable them “to keep beer very fresh and share them with friends and family,” again reinforcing the growler’s importance of sharing. Crowlers are also lighter, more durable, and better for beer in terms of keeping it safe from sunlight and air, McCulla adds.

Are Growlers Obsolete?

As craft beer culture evolves, so, too, has its vessels. Cans are king for craft beer geeks today, particularly the craft beer mongers among us who drink and deal almost exclusively with beer packaged in cans that are smartly designed, 16 ounces tall, and filled with something hazy.

Yet, if the growler’s 19th-century origins, 1980s resurgence, and current adaptations tell us anything, it’s that beer, and tastes, are cyclical. This practical, shareable jug isn’t going anywhere.