Chianti has been one of the most ubiquitous wines since even before Hannibal Lecter suggested it as a pairing with liver and fava beans. The wine, hailing from the region of the same name, is known for drinkability, cost-effectiveness, and a flavor profile consisting of red cherry fruit, herbal notes, and a touch of earth. However, there’s more to Chianti than meets the eye, and with eight subregions, hundreds of producers, and an exceedingly picturesque landscape, it’s worth exploring this well-known region in greater depth.

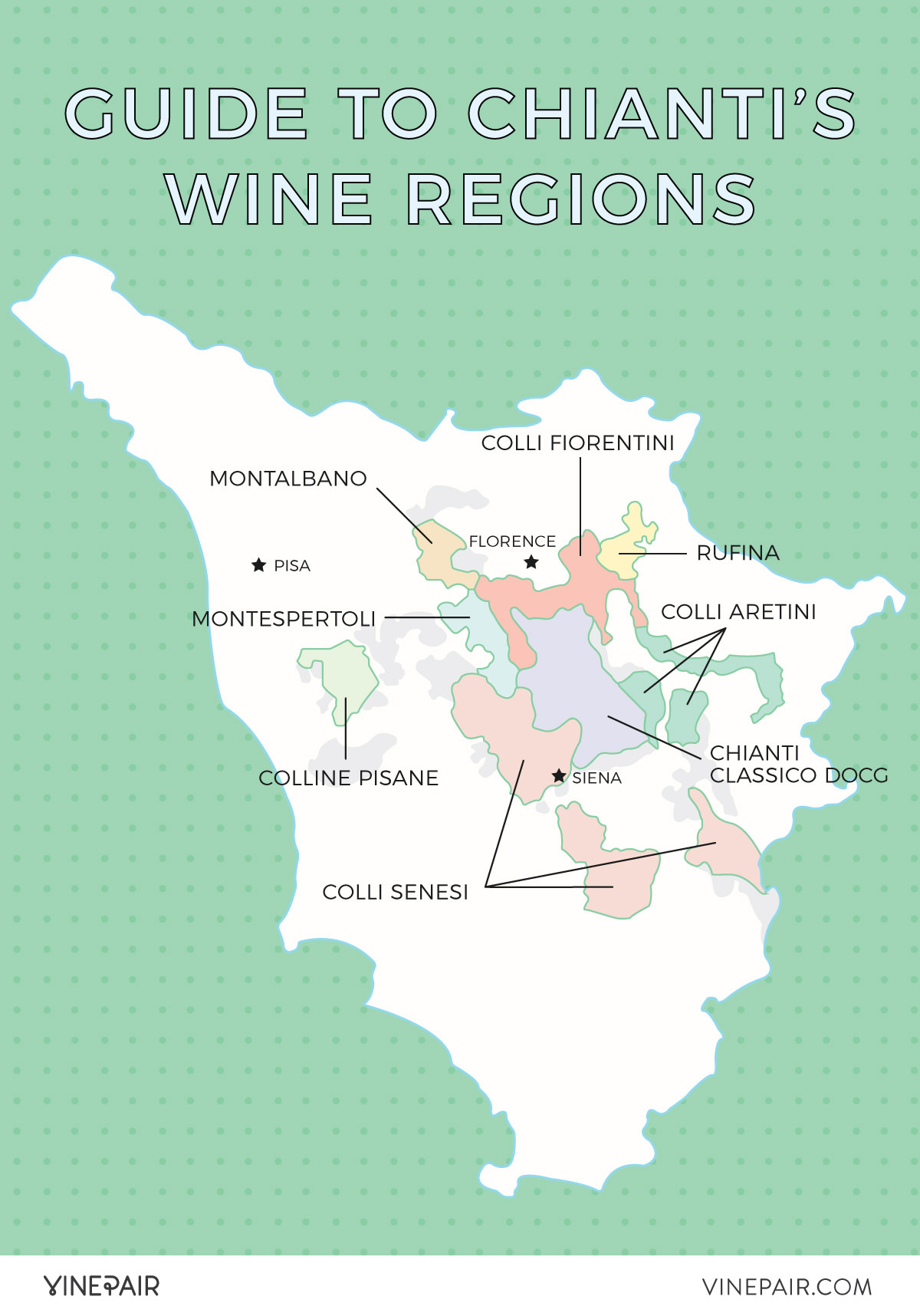

Looking for a detailed breakdown of all there is to know about the regions of Chianti? Keep scrolling beyond our Chianti map!

The Basics

The overall region of Chianti is located in Tuscany, largely situated between the cities of Florence and Siena, with some areas extending toward Pisa. Most would be surprised to see just how large Chianti is; it stretches over 100 miles from north to south and covers much of Tuscany, overlapping some of the region’s most famous appellations. Chianti is always a red, Sangiovese-based wine, and while the historic Chianti blend (credited to Barone Ricasoli in the 1800s) was comprised of 70 percent Sangiovese, 15 percent Canaiolo, and 15 percent Malvasia Bianca (yes – a white grape!), restrictions are less strict now and it may either be a blended or varietal wine. Any of Chianti’s subregions may produce wines in normale, superiore, or riserva styles, all of which have aging requirements that may differ slightly based on the subregion. Most Chianti wines may be released about six months after the harvest, in March, but some subregions specify longer aging.

Chianti DOCG

The borders of the Chianti region as it is known today were formed in 1932 and were decidedly much larger than the classic heart of Chianti wine production. The region became one of Italy’s first DOCs, created just after the category emerged in 1963, and was elevated to DOCG in the 1980s. The size of Chianti is part of the reason the wine is so well known; it’s easy to produce large volumes of inexpensive wine that can reach restaurants and shops around the world. It is also the reason why the quality of Chianti wine is so variable, as plenty of subpar vineyards are technically allowed to label their wines as Chianti DOCG.

This is why the subregions of Chianti are so important; they can help to distinguish a higher-quality, more terroir-driven wine from a generic one. The best Chianti wines come from hilly areas, which is why it is no coincidence that many of the subregions have some version of the word colli or colline in them; this translates to “hills” in Italian. Driving through Chianti — particularly the heart of the region, Chianti Classico — is a test in road skills and stomach strength, as the roads wind up, down, around, and through the hills that separate one town from another. It’s important to note that other than Chianti Classico, each of Chianti’s subregions do not have their own legal appellations but are all allowed to label their wines as Chianti DOCG, with the name of the subregion included as well.

Chianti Classico DOCG

As the word “classico” typically denotes in Italy, Chianti Classico covers the vineyard area that was historically the heart of Chianti winemaking. Chianti, in fact, was the first zone in Italy to be officially delimited, as it was designated by the Medicis in 1716. This original 1716 designation falls entirely within the modern Chianti Classico zone, covering the four principal villages of Radda, Gaiole, Castellina, and later, Greve, all of which then appended their village names with the words “in Chianti.”

Chianti Classico is by far the most important subregion of Chianti and is the only one to hold its own DOCG, signifying its high level of quality over the other subzones. There is wide soil variation, but the most important soils in Chianti Classico are galestro, a soft, clay-like soil that breaks apart easily, and albarese, a hard sandstone. Overall, the wines from here have the most potential to age of all Chianti wines, with high acidity and noticeable tannic structure despite their medium to medium-plus body. Chianti Classico style depends on the vineyard and producer, but some do choose to age their wines in new oak. As for the four key towns of Chianti Classico, their differing terroirs leads to differences in style as well: Greve in Chianti has full, concentrated flavors; Radda in Chianti is exceptionally high-toned and elegant; Gaiole in Chianti is known for structure and bright acidity due to elevation; and Castellina in Chianti is richer and more plush due to high proportions of clay.

Chianti Rùfina

Located east of Florence, Chianti Rùfina is the smallest subregion of Chianti but also the most well known, consistent, and distinctive area, excepting Chianti Classico. It’s nestled into the foothills of the Apennine Mountains, the range that runs down the spine of Italy, and a pass just north of Rùfina allows breezes to cool the vineyards, particularly in the summer. This leads to wines that are elegant and ageable. Chianti Rùfina may not be released for a full year after harvest, six months longer than the typical Chianti.

Chianti Colli Senesi

Chianti Colli Senesi is a large subregion of Chianti, covering some of the most famed vineyard areas in all of Tuscany, as it overlaps portions of Vernaccia di San Gimignano, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, and Brunello di Montalcino in the hills surrounding Siena. If one were assessing the subregions of Chianti by land quality alone, Colli Senesi would probably surpass Rùfina in terms of importance. The situation is a Catch-22, however; because Colli Senesi overlaps these more famous — and therefore more profitable — designations, the appellation is typically used only for less-prestigious Sangiovese vineyards. Therefore, Chianti Colli Senesi wines are not seen as often as those of other regions. Despite this, the wines tend to have elegance and an easygoing, fruit-forward character with little use of new oak.

Chianti Colli Fiorentini

The area in the hills south of the city of Florence, separating the city from the Chianti Classico zone, is known as Chianti Colli Fiorentini. The wines are generally light, fruity, and easygoing, meant to be consumed young; in fact they rarely make it past the trattorias of the nearby city. There is some influx of new money into these vineyards from wealthy Florence dwellers, but the subregion remains under the radar. Chianti Colli Fiorentini wines may not be released for a full year after harvest, six months longer than the typical Chianti.

Chianti Colline Pisane

While not the most recognizable area of Chianti, Colline Pisane has the most unique location of the subregions, as it is located in the hills near Pisa, set apart from the majority of Chianti. Here the vineyards are lower and closer to the sea, so the climate is milder and has less rainfall. Colline Pisane wines tend to be very light in body and color, with soft fruit and violet notes.

Chianti Colli Aretini

Three non-contiguous regions toward the eastern limits of the Chianti appellations are known as Chianti Colli Aretini. Parts of Colli Aretini border the Classico zone, but because the subregion isn’t very well known, the wine coming from these areas is more often labeled simply as Chianti DOCG. Colli Aretini wines tend to be simpler, with aggressive acidity.

Chianti Montalbano

The small Chanti Montalbano area is located in the Montalbano hills west and slightly north of Florence. The region overlaps with another red-wine appellation, Carmignano DOCG, which overshadows Chianti Montalbano due to its higher proportion of Cabernet Sauvignon and therefore more-intense flavor profile. Sangiovese vineyards on the west side of the Montalbano hills, where there is more sandstone, are often used for Chianti Montalbano, creating a typically light, fruit-driven style of wine meant to be consumed young.

Chianti Montespertoli

Unlike the other subregions of Chianti, Montespertoli was given its own designation in 1997. It was once part of the Colli Fiorentini region and now lies just to the west of it, in the hills around Montespertoli. Chianti Montespertoli wines may not be released until June after the harvest, three months longer than the typical Chianti.