Half a decade ago, Dick Cantwell coined one of the greatest pejoratives I’ve ever heard: “hate tourists.” It’s how the Elysian Brewing Company co-founder described the craft beer true believers who traveled to Seattle from near and far to cause trouble at the company’s taprooms after news of its sale to Anheuser-Busch InBev hit the headlines in 2015.

“Our service staff took it on the chin. … People were buying beers [at Elysian’s Seattle pubs] and literally dumping them on the floor,” Cantwell told me in an interview a year after the deal. The conversation was part of my reporting for a feature about the rising cultural anguish at Big Beer’s newfound acquisition appetite for craft breweries, which would eventually run under the headline “The Great Craft Beer Sellout.” This was a heady moment. After morphing from crunchy sideshow to full-flavored phenomenon, the American craft brewing industry was growing like mad. Tensions ran high that macrobrewers would co-opt and commodify the sector’s indelible anti-corporate cachet, and those small independent breweries that did deals with the Goliaths last decade were considered as naive as Samson and as treacherous as Judas.

But half a dozen years later, the idea of meeting brewery sales with Old Testament vitriol seems downright antiquated. Over the past 18 months, the craft brewing industry has seen an uptick of acquisitions, roll-ups, and mergers at a pace reminiscent of last decade’s M&A mayhem. The latest, a buyout of the CANarchy portfolio (anchored by Oskar Blues and Cigar City, which remain prominent O.G. craft brands despite slipping sales) even carried a nine-figure price tag befitting a big bad corporate buyer. But rather than scorn for the sellouts, these deals — to macrobrewers, private equity firms, and industry outsiders — have received a decidedly more muted response.

“I don’t know if the best way to [describe] it is diminishing returns or if it’s just sort of exhaustion,” says Chris Shepard, a senior editor of Beer Marketer’s Insights, a trade publisher. “But over time, folks have just sort of understood that that’s the way things go.”

As someone who’s covered the seething angst and vexing contradictions of America’s craft beer industry and culture for over a decade, I find this a remarkable development. Where have all the hate tourists gone? Or, to put it another way: How did a craft beer industry and community so opposed to selling out become so inert in the face of their beloved breweries getting sold off?

Primed pump

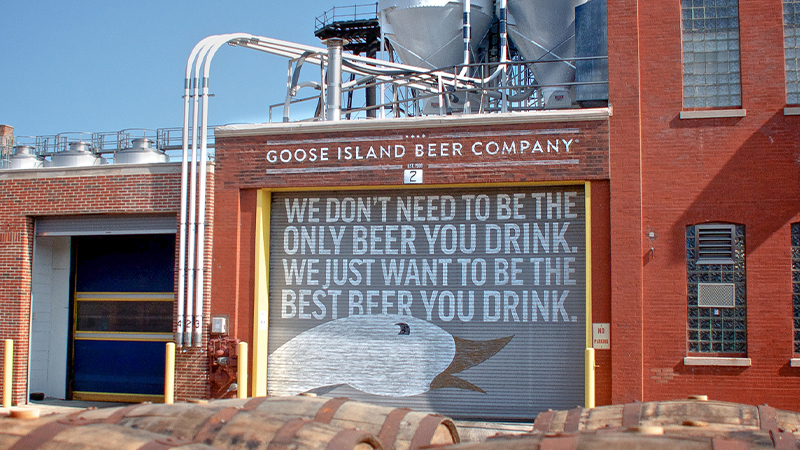

Conversations about craft brewery sellouts usually start with Goose Island’s 2011 acquisition by Anheuser-Busch InBev, which turned out to be the first of 11 deals the world’s biggest beer company would ink in its push into the craft brewing category last decade. Josh Noel, a Chicago Tribune reporter who cataloged ABI’s tear in 2018’s “Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out: Goose Island, Anheuser-Busch, and How Craft Beer Became Big Business,” says that what was then astonishing has since become commonplace.

“It was all fresh and new then, and therefore surprising,” he tells VinePair. “It really was a shift from what craft beer had been to the thing it was becoming, and now I think it’s become that thing. So the ensuing sales are just less jarring.” Time may not heal all wounds, but after a while, the pain of watching Big Beer’s major players buy their way into craft beer’s walled garden became more tolerable — or at least enough of a given that howling about it in public just seemed silly.

The thing craft beer became over that period was “big business,” as the subtitle of Noel’s book spells out. The influx of new players, the spectacular growth, and the undeniable demand from the American drinking public all brought legitimacy, primacy, and new urgency to the craft brewing industry. Bigger craft breweries are more complex businesses, and operating like renegade outsiders at scale is a recipe for chaos. (Just ask BrewDog.) Thus the appeal of strategic partners like ABI, Molson Coors, Heineken, and Constellation, all of which scooped up craft breweries in those years. Whether breweries were acquired, or simply forced to compete with those that had been, it contributed toward a mounting professionalism in the sector — at least compared to its overconfident, undercapitalized, and defiantly grassrooted former self. This corporatization helped to blunt the furor.

“Years ago there were people — whether it was consumers or other industry members — that sort of took some of the deals personally, it felt like an attack,” says Shepard. The excommunications from the craft brewing community that followed those acquisitions were accordingly emotional. Drinkers, whether they ever practiced hate tourism in real life, torched those acquired breweries on social media. Beer bars and craft bottle shops (which were then far more influential in advancing the craft beer cause) canceled the accounts of breweries that had left the fold. Microbrewers turned their backs on longtime friends.

“That big cultural buildup that affected the so-called millennials back when they were still really the hot thing, … you can’t expect that kind of tribal enthusiasm to last that long,” says Maureen Ogle, historian, author of “Ambitious Brew,” and longtime industry observer. A decade of sales, competition, and stiff headwinds have forced industry participants and drinkers themselves to accept a commercial pragmatism that would’ve seemed almost heretical when the money first started flying. “It’s just that the industry has changed, more than the people have changed,” says Noel.

Muddy narrative/different buyers

Meanwhile, drinkers — fickle creatures that we are — who had once feted craft beer for its vast array of flavors, got a taste for beverages beyond the scope of America’s small independent breweries. Hard seltzer, canned cocktails, and other “beyond beer” offerings blurred lines for consumers and producers alike. You and I see this shift in supermarket beer aisles, which are stocked these days with drinks that are only beer by technicality and tax code. But changing tastes have also brought a new set of buyers to the table that place nowhere in the tidy, triumphal David-versus-Goliath narrative that once animated the passions of craft beer fans and brewers.

“Back in the day, there was Big Beer and there was craft beer and there really was a pretty clean line between the two,” Noel says. “The black and white is now pretty gray.”

Consider the companies that are writing the checks to acquire craft breweries over the past year and a half. It’s not craft beer’s arch-nemesis ABI; it’s not even any other familiar beer business heavies. A Canadian cannabis conglomerate picked up SweetWater in December 2020, then long-suffering San Diegan outfits Green Flash and Alpine in December 2021. CANarchy’s new dad is Monster Beverage Corporation, an energy drink behemoth that dropped $330 million for the portfolio in mid-January.

These are different buyers, says Townsend Ziebold, a managing director at Cowen and Company, who focuses on the beverage sector. “The market has moved from high-synergy domestic strategics buying brands, to companies that are looking from the outside at the craft beer industry, looking for a platform.” It’s not that these firms aren’t as sharp-elbowed and corporate as the Big Beer overlords that craft brewers revolted against. Only time will tell on that front, though some brewers are already preparing for the worst. But coming from outside the beer industry, they carry much less cultural baggage, and make for much less obvious villains off the bat.

“We’re just seeing this next level of absurdity in the whole equation, and I think that results in a lot less gnashing of teeth, because who cares?” says Noel. Big Energy buying Oskars Blues? Big Weed buying the company that makes 420 Extra Pale Ale? “Even though there are probably really good structural business reasons to do it … it’s just kinda more silly than anything,” Noel says.

Even the recent buyers that are in the beer business are not the stereotypical bad guys. Kings & Convicts, which took Ballast Point off Constellation’s hands for less than a dime on the dollar in 2019, just relieved Molson Coors of Saint Archer’s production facility in San Diego this month. It’s technically a craft brewery (albeit one with deep pockets) helmed by a hotelier-turned-homebrewer with a remarkable eye for distressed assets. The private equity firm that bought Uinta in 2019 just sold the struggling Utah brewer to U.S. Beverage, a longtime importer/marketer. A different private equity firm bought Catawba Brewing Co.’s Carolina-based empire to round out its Southeastern roll-up. These just aren’t hulking conglomerates that inspire disdain in the general drinking public — to the extent that the general drinking public even frets over which company owns their favorite beer brands at this point.

Some experts think that extent is minimal these days. “Retailers and most definitely the VAST majority of beer drinkers don’t care who owns what brewery or brands,” Bump Williams, a four-decade veteran of the consumer packaged goods business who runs a beer consultancy that bears his name, tells me via email. “All they care about is getting the product delivered to their shelves in time to make a shopper happy to buy it.”

Which brings us to Bell’s.

Sobering realities

In November 2021, news broke that Michigan’s beloved Bell’s Brewing Company would be acquired by Japanese mega-brewer Kirin. (Technically it was acquired by New Belgium, which is a subsidiary of Little Lion World Beverages, which is a subsidiary of Kirin, but you get the point.) Founded in 1987, Bell’s was one of the few pioneers of the early craft brewing era that had remained fully independent the whole time; now it was “selling out” to a corporate player. Reactions to the deal (terms of which were not disclosed) were not categorically positive, but the backlash was nothing on the order of the old days.

“I remember seeing a little [backlash] on Twitter, but certainly a lot less than if Bell’s had sold 10 years ago, and if Bell’s had sold to Anheuser-Busch,” says Noel. “It was like night and day, in terms of that.”

There are two main reasons for this. First, despite being a bona fide macrobrewer, Kirin is far less familiar to — and so strikes far less fear in — the American drinking public than any of last decade’s strategic buyers. “Kirin is Big Beer, make no mistake, but by folding in with New Belgium, it felt very different than jumping into the Anheuser-Busch pipeline to be shot out into every convenience store in America,” Noel says. Despite controlling a plurality of its home market and being one of the world’s largest beer makers, the Japanese conglomerate has made inroads into the lucrative American market without drawing the same ire or scrutiny as its higher-profile global rivals.

The slow, methodical pace of its U.S. craft brewing acquisitions probably helps perception of its posture, too. After buying a 24 percent stake in Brooklyn Brewery in 2016, it acquired New Belgium Brewery in 2019, then Bell’s. By contrast, other firms’ buyouts occasionally gave the impression that the buyer wasn’t sure what they were buying, Constellation’s billion-dollar Ballast Point bust being the chief example. Last decade’s frenzied hoovering unnerved craft beer industry types and diehard consumers at the time. But by moving into the U.S. craft market a bit later, Kirin has benefited from watching its peers go first, avoiding their mistakes while laying sturdy groundwork that demonstrates a coherent strategy for the category. As a result, the Japanese firm looks nothing like a spoiled child clamoring after a shiny toy it’ll quickly tire of, and much more like a disciplined long-hauler.

“The appetite and the possibility for this broader organization in the U.S. is coming into a little clearer light,” says Shepard. Kirin’s Little Lion-led acquisition of the Michigan outfit “sort of helped solidify the fact that this is a company that wants to be a player, or a big player or the big player, in U.S. craft.”

Like pretty much everyone else I interviewed for this story, Shepard considers the Bell’s deal thematically distinct from the others mentioned above. The basis for that belief is also the second reason the sale didn’t draw much beer dumping or cultural lament: Bell’s, a top-10 craft brewer with strong brands and an enviable distribution network, was not an underperforming asset to be unloaded. It was a life’s work that came to a natural endpoint.

The company’s founder and namesake, Larry Bell, was able to go out on top after nearly four decades at the helm with a (presumably lucrative) exit. “Larry, after the last few years, had sort of finally gotten to the point that a lot of founders of the oldest craft breweries in the country have gotten to: “OK, it’s time for me to retire, it’s time for me to move on. What is the solution to that?” Without an heir apparent waiting in the wings, the only realistic move was selling the brewery to his employees or an outside buyer, and Larry opted for the latter.

It’s hard to blame him, says Noel. “If you know the backstory, if you know the landscape, … I mean, what else was he gonna do?”

It’s a sobering reality of the maturing craft brewing business these days. Many of the iconic firms and founders that have built the industry are getting long in the tooth. (“In the top ranks, there’s not many of us left,” Bell told the Kalamazoo Encore in September 2021.) Having built successful businesses, those pioneers must eventually find a willing buyer with enough scratch to send them off to retirement. The only alternative is shutting down, and only the most delirious craft brewing zealots would argue that a closed brewery is preferable to an acquired one.

Another sobering reality: this business is getting harder. While Bell’s was successful and healthy at the time of sale, U.S. craft brewers have an increasingly tough row to hoe these days. There’s pandemic uncertainty, slowing sectoral growth, supply chain issues — you name it. And whether it’s an aging founder or an impatient investor, no one relishes pushing through lean years. “[C]raft breweries were darlings of the beverage alcohol industry just a decade ago, [but] investors are no longer patient with them beyond typical investment timeframes,” wrote journalist Kate Bernot for Good Beer Hunting analyzing the Uinta and Saint Archer deals earlier this year. “Like companies in any other industry, an infusion of money from private equity or multinational conglomerates still means someone is watching the clock.”

The dance goes on

I’ve argued elsewhere that Kirin’s Bell’s buyout signaled the end of craft brewing’s “movement” moment, because it sent one of the last true-blue craft beer pioneers riding into the sunset. There simply aren’t that many first-generation standard-bearers still standing after all these years.

But even if it’s no longer a movement (or ever was), craft brewing is still a business, and a big one. Absent the rending of flannels and the plucking of neckbeards, what can we expect from the Great American Craft Beer Sell-Off?

Almost certainly, we’ll see more sales. Ziebold likens the current craft brewing M&A landscape as a game of musical chairs, in which willing sellers circle a limited number of buyers, looking for an exit. “The music will always play, I think, and there will always be a level of [acquisition] activity,” he says. “But the buyer pool is limited.” In other words, if you’re the founder of a sizable craft brewery hoping to sell, you’ve only got a few potential partners out there. And every new deal in 2022 is one more chair removed from the circle.

The cultural implications are harder to suss out. What will happen now that drinkers (and plenty of brewers, too) have mellowed on corporate ownership and accepted the inevitability of sellouts? “American beer culture is never going to be as entrenched and inbred the way it was with people who emigrated here from Northern Europe, who came from a genuinely beer-dependent or beer-centric culture,” says Maureen Ogle, always reliable for a wide-lens historical perspective. “We’re just never going to have that in this country.”

At its zenith, craft beer might have achieved something close to that kind of social, civic saturation, but those days are in the rearview now. That doesn’t mean full-flavored beers are going anywhere, but the hate tourists showing up to dump them on the floor are pretty much gone. Being mad all the time is exhausting — especially if you’re not even sure who you’re supposed to be mad at anymore.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!