“Champagne is just wine,” physicist Roberto Zenit said. “What makes it special is the carbonation.”

It’s true: We love our bubbles. In 2017, the world guzzled 544 million bottles ($913 million) of Prosecco, 307 million bottles ($5.6 billion) of Champagne, and approximately 550 billion bottles ($661 billion) of beer.

Although fermentation naturally imparts some carbonation to beer and wine (thanks, yeast!), a majority of bubbly beverages are force-carbonated to achieve a precise gas-to-liquid ratio. Their appeal is a scientific mystery. Like spicy foods, carbonation triggers pain receptors in the brain indicating we should turn away from such aggressive attacks on our palates. “But,” Zenit and Javier Rodríguez-Rodríguez write in a recent study, “humans appear to enjoy the mildly irritating effects.”

Though we may not know why we love spritzy drinks so much, we at least know this: Our current obsession with Spindrift, and much of the world’s thirst for bubbles, is thanks to Joseph Priestley, an 18th-century genius-of-all-trades.

Bubbles: A Brief History

Priestly was a British chemist, theologian, educator, and author who, along with authoring guides to electricity and grammar, and founding Unitarianism, pioneered the scientific study of “airs,” or gases. He is best known for discovering oxygen and inventing carbonated water.

In the early 1770s, Priestley lived near a brewery in Leeds where he conducted various experiments. He noticed that water left above a beer vat acquired a flavor and texture similar to that of mineral spring water, and he called this phenomenon “fixed air.” Though he did not know at the time, fermenting wort was releasing carbon dioxide into the water.

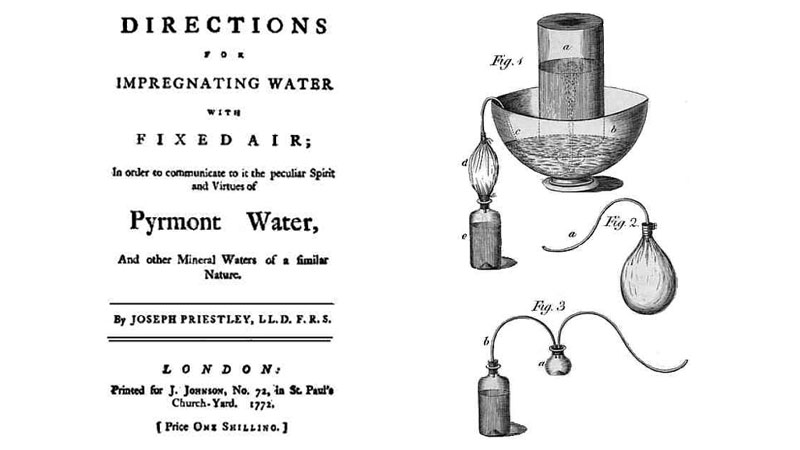

In 1772, Priestley published “Directions for Impregnating Water With Fixed Air,” illustrating how one might force “fixed air” (carbon dioxide) into water, creating effervescence (carbonation) that mimics mineral springs.

Priestley had no plans for commercializing his discovery of carbonation, but another scientist saw the spritzy liquid’s consumer appeal. His name was Johann Jacob Schweppe, and he founded the Schweppes Company in 1793.

Bursts of Joy

Of course, Priestly did not invent bubbles themselves. As early as the 18th century B.C., the “Hymn to Ninkasi” detailed the beer-making process. The earliest chemical evidence of beer was discovered inside 2,500-year-old clay drinking vessels in northern Iraq last year.

And as legend has it, a 17th-century French Benedictine monk tasked with removing excess air from his abbey’s Champagne bottles famously tasted the re-fermented wine and declared, “Come quickly brothers, I am drinking stars!” His name? Dom Perignon, the very monk known for improving the méthode champenoise, as well as becoming the namesake of the eponymous Moët and Chandon tête de cuvée.

Indeed, the world had to wait until 1838 for Cagniard de Latour to discover that yeast adds carbonation to beer, and until the 1850s for yeasts to be understood as microbes responsible for alcoholic fermentation. Until then, brewers and vintners considered fermentation an act of the gods.

But, man-made or magic, the pleasures of bubbles are as mysterious today as their origins were centuries ago. Sometimes the best things come out of thin air.