In June, a group of former employees of the Scottish craft brewer BrewDog published an open letter accusing the firm of behaving less like a “punk” craft outfit and more like the rapacious multinational macrobrewers it set out to counter. “Growth, at all costs, has always been perceived as the number one focus for the company, and the fuel you have used to achieve it is controversy,” read the letter, which has since been signed by over 300 former workers from the rapidly expanding craft brewer. Calling themselves “Punks with a Purpose,” the authors detailed a “rotten” company culture dominated by fear, greed, and exploitation. “In a post-truth world, you have allowed the ends to justify the means, time and time again,” they said.

The letter marked the latest scandal in a decade-long cloud that stretches over BrewDog’s rise to global prominence in the craft beer industry. Despite a steady drumbeat of controversies, BrewDog, founded in 2007 outside of Aberdeen by partners James Watt and Martin Dickie, has thrived. It is Europe’s leading craft brewer, and its bars and brewing operations can now be found in the United States, Germany, and Australia. The “Good Ship BrewDog,” as Watt (a former fishing captain) is fond of calling it, hopes to build a new brewery in Asia as soon as next year.

All the expansion comes at a cost. If BrewDog’s former workers are to be believed, the company’s remarkable rise has been paid for with their blood, sweat, and tears. More literally, it’s been paid for with money, over $100 million of which has come from sales of shares to rank-and-file drinkers. These “Equity Punks,” as they’re called, have bought into BrewDog’s disruptive outsider model via its powerful, industry-leading crowdfunding program known as Equity for Punks (EFP), with average-Joe fans purchasing stock to help underwrite BrewDog’s international expansion. The program, which has delivered a consistent stream of cash to BrewDog’s coffers nearly annually since its inaugural run over a decade ago, is integral to the enterprise. Watt, the company’s chief executive and frontman, is fond of saying that equity punks are BrewDog’s “heart and soul,” but they also help line its wallet.

Currently, the company is running two EFP crowdfunding campaigns, one in the U.K. and one in the U.S. Both are named “Tomorrow,” a nod to the company’s promise to use the money raised to reduce the environmental impact of its operations. Watt and Dickie have said this will be its last before the Scottish parent company, BrewDog public limited company (plc), becomes a publicly traded company.

What they don’t say — not loudly, at least — is that new investors, especially in the U.S., stand very little chance of seeing a return on their investment if the Scottish brewer goes public. But that is what BrewDog’s financial filings and EFP materials suggest. Those documents indicate that the company is overvalued, and that a major private equity firm’s holdings will cut into plc punks’ returns at an IPO unless the company can keep growing at industry-beating rates. Meanwhile, the structure of its U.S. subsidiary allows BrewDog proper, and its CEO, to grab low-risk cash from credulous American equity punks beguiled by the company’s “anti-business business model” without offering them any clear way of participating in any future public listing.

“It’s just a really bad situation for those punks,” remarked one independent analyst after examining the current American EFP offering.

BrewDog declined to make an executive available to interview for this story. The self-styled renegade brewer also refused to answer any of the 20 detailed questions VinePair sent via email about its EFP program, U.S. subsidiary, and other relevant aspects of its business. But VinePair’s reporting shows that even as the Scottish brewer touts its growth and stokes anticipation of an IPO, BrewDog’s investment offer to American fans is long on risk, short on reward, and overpriced to boot. Here’s a closer look at our findings.

The EFP “secret weapon”

Many have pointed out the naked contradiction of a company marketing itself as “punk” while accepting private-equity funding and engaging in sophisticated financial maneuvers. But few have ever reported on just how sophisticated those maneuvers are.

BrewDog’s ability to convert fans and drinkers into investors who’ll fund its exploits dates back to 2009. After lying their way into a bank loan the year prior, Watt and Dickie turned to crowdfunding to finance the then-small brewery’s growth, bringing in a reported $975,000 from 1,330 investors. This was EFP I, and more would soon follow. Since then, BrewDog has run such a raise roughly every year, refining the model with which it has convinced 200,000 fans to exchange hard-earned cash for shares in the company. Today, EFP is a powerful growth engine that Forbes deputy business editor Kristin Stoller dubbed BrewDog’s “secret weapon.” Secret, the program is not. But it is formidable. At publication, the company’s current EFP rounds in the U.S. and U.K. have raised $585,000 and £27.5 million, respectively; a conservative tally of funds raised in 11 EFP rounds to date puts the total take for BrewDog plc, and its American and Australian subsidiaries, well north of $100 million. “It’s an amazing business model because we don’t see [equity punks] as investors,” Watt told Stoller in January 2020. “They’re advocates, they’re ambassadors, they’re on this journey with us.”

Equity punks are investors by definition. But Watt is right that EFP is an amazing business model. In a world where anyone with a smartphone can easily invest in highly regulated, easily traded securities on mainstream financial exchanges, the fact that BrewDog has been able to convince investors to buy their less regulated, illiquid shares is a testament to the company’s capacity for self-mythology. But it’s not just slick marketing that lures potential investors in. The company used to hawk the shares alongside beers in its bars, and has long offered a variety of perks to equity punks that increase with the size of investment. These bonuses range from very basic (a free beer on your birthday, discounts at the company’s 100-plus global bars) to merchandise, more booze, and exclusive experiences.

For example, a U.S. investor who buys a single $60 share in the American firm today gets a lifetime discount of 5 percent at BrewDog’s taprooms and online stores; if they buy $3,000 worth of shares, they’re entitled to a YETI cooler full of BrewDog beer, among other beer and swag. Of course, equity punks would be hard-pressed to recoup their investment from these perks alone.They’d have to knock back $1,200 worth of BrewDog food and drink at one of the company’s U.S. taprooms (or run up that tab at the company’s online store) to clear the $60 share price. If it’s YETIs they’re after, they could buy 10 of the brand’s popular Tundra 35 coolers for $3,000, and still have enough cash left over for oodles of BrewDog beer and merch, too. But for potential punks intrigued by the idea of investing in a brewery, these loyalty club-style perks sweeten the deal. Or at least they’re supposed to.

Posts on the shareholders-only, company-run BrewDog EFP forum, reviewed by VinePair, suggest that the brewer has at times struggled to deliver on the perks it has promised its punks. A November 2020 thread has become a 2,000-posts-and-counting clearinghouse for equity punks’ grievances, ranging from long-delayed deliveries and reduced “lifetime” discounts, to poor communication from the company in which they’ve invested. “By the way still no EFP beer after waiting nearly 2 years,” posted a frustrated punk. “For a beer company that makes beer, wastes beer, pours away beer, makes more beer … is it really too much to send said beer to it’s [sic] shareholders as promised?”

If the perk problems become too much to bear, punks have just two options to cash out: find someone willing to buy their shares, or engage a dedicated third-party broker that specializes in liquidating BrewDog stock. (Yes, they exist.) Over the past decade, the company also sponsored annual “trading days” to facilitate equity punks buying and selling shares from one another more easily, though the practice was canceled during the coronavirus pandemic and has not resumed this year. At the January 2019 event, the price for BrewDog plc shares settled at around £15, around 40 percent cheaper than the company is currently selling them to equity punks. In fairness, that was over two years ago, and the limited trade volume was such that it’s hard to say BrewDog plc shares were “worth” £15 at that point. Then again, ambiguity around the value of BrewDog equity is a bit of a recurring theme.

The valuation calculation

In 2017, TSG Consumer Partners, a top private equity firm, invested around £213 million for around 22 percent of BrewDog, implying that the firm was worth about £1 billion overall. In marketing materials and press coverage at the time, BrewDog touted the deal as a colossal return on investment for early-adopting equity punks, a validation of its “democratiz[ed]” financing model, and suggested that it paved the way for even better returns ahead. “Our Equity Punks now own part of an independent business that has attracted an awesome partner who will help grow their investment even further,” said Watt in a 2017 statement.

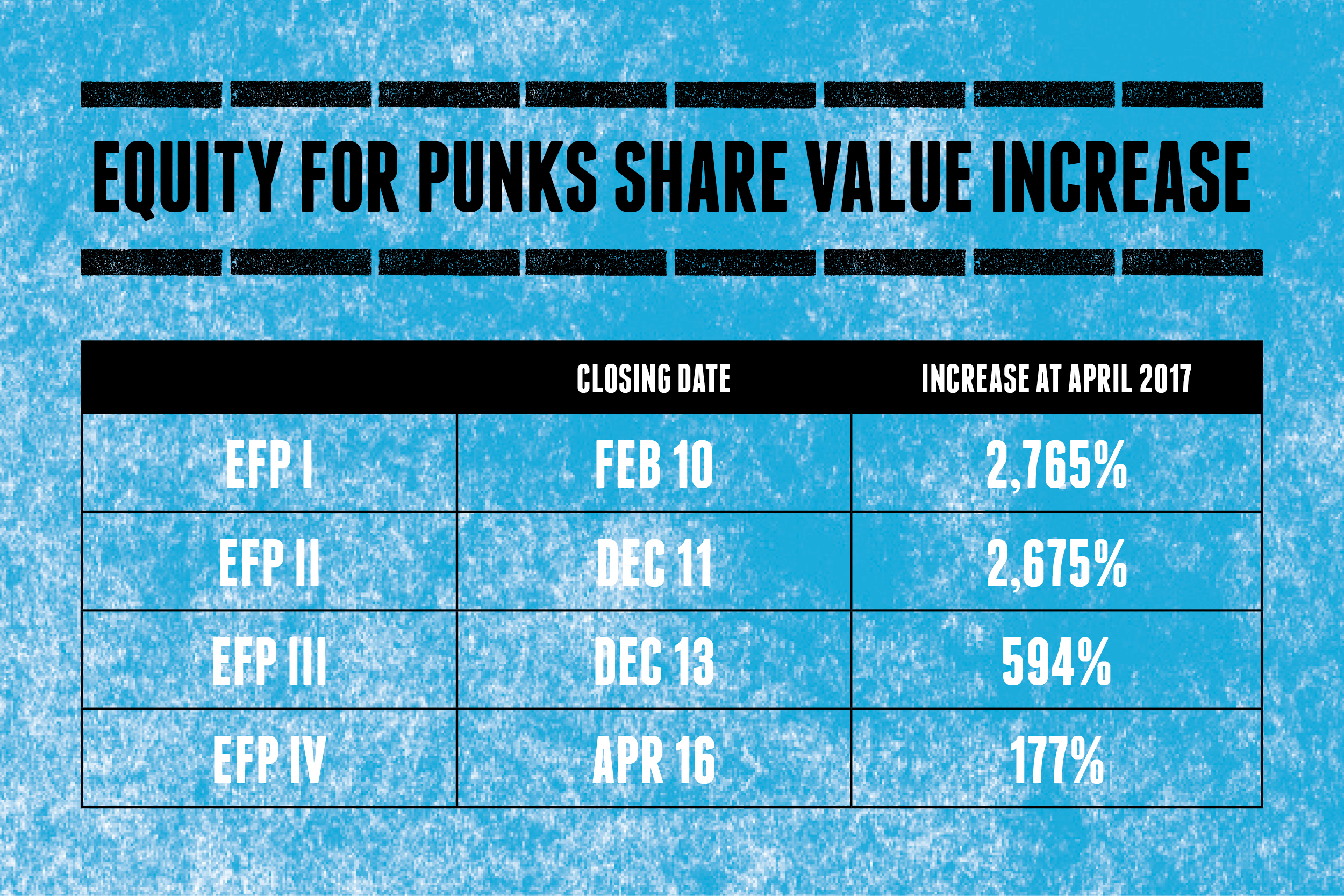

Long-haul equity punks may have enjoyed serious market-beating returns thanks to the TSG deal. The S&P 500 returned one-year investors 18.75 percent in 2017; BrewDog shares bought in that year’s EFP IV round would have returned 177 percent. Punks who got in earlier saw even higher returns, according to contemporary reports, not to mention the chart BrewDog published celebrating the deal. But because they were limited to selling 40 shares or fewer, equity punks couldn’t cash out entirely at that point. Depending on the total they invested, their overall gain may be substantially lower when (or if) the long-hinted-at IPO happens.

BrewDog’s critics decried the deal as a sellout of the brand’s professed anti-establishment ethos, something Watt and Dickie denied. Though the co-founders still remain the company’s majority shareholders, along with other insiders, the pair cashed out around millions of shares at the time, substantially reducing their risk and making tens of millions of pounds apiece in the process.

Is any of this punk? Your mileage may vary. But more pressing, from a potential investor’s perspective, is what the structure of TSG’s investment — omitted from the brewer’s triumphal press release about the deal, but detailed in subsequent EFP prospectuses — suggests about BrewDog’s actual value.

The firm, which manages some $10 billion in assets — and, with a portfolio that has included SweetWater Brewing Company and Duckhorn Vineyards, knows its way around a beverage-alcohol company’s books — didn’t buy the same shares that BrewDog was selling to punks (known as Common B), or even the shares held by insiders like Watt and Dickie (Common A.) Instead, the private equity firm bought a new, discounted class of shares called Preferred C, at an average price of £13.18 apiece — nearly 45 percent off the share price BrewDog offered in an EFP round that same year. (In years since, the company has repeatedly raised per-share price; the current shares go for £25.15 in the U.K. and $60 in the U.S.) In addition to being cheaper, TSG’s special shares also entitle it to a guaranteed 18 percent compound annual return in any liquidity event, be it an IPO, acquisition, or bankruptcy. Crucially, BrewDog must pay out the private-equity firm before other shareholders, meaning that punks who buy shares today could lose money if BrewDog doesn’t grow fast enough to outpace its growing I.O.U. to TSG.

Three investment professionals with over 30 years of combined experience analyzing the global brewing industry told VinePair that, while the structure of the private-equity deal was not unusual, the 18 percent “coupon” suggests TSG considered BrewDog an especially risky investment. (Those professionals requested anonymity because they were not authorized by their firms to speak with the media.)

“This begs the question: What did TSG think BrewDog plc was worth?” says Ben Ostrow, founder and lead at Apsara Partners, an investment manager specializing in financing ownership transitions. The former private-equity investment analyst first began exploring the company’s financial filings after being served social media ads that encouraged him to invest in the current U.S. EFP round. (Disclosures: Ostrow and the reporter are personal acquaintances. Ostrow does not hold or manage positions in either BrewDog or any other beverage company.)

“My suspicion is that TSG thought the value of BrewDog was much lower” than the £1 billion figure the Scottish brewer claimed in 2017, continues Ostrow. Through a representative, TSG declined to comment. But the notion that BrewDog is overstating its value to investors comports with analysis of BrewDog’s public filings and EFP documents.

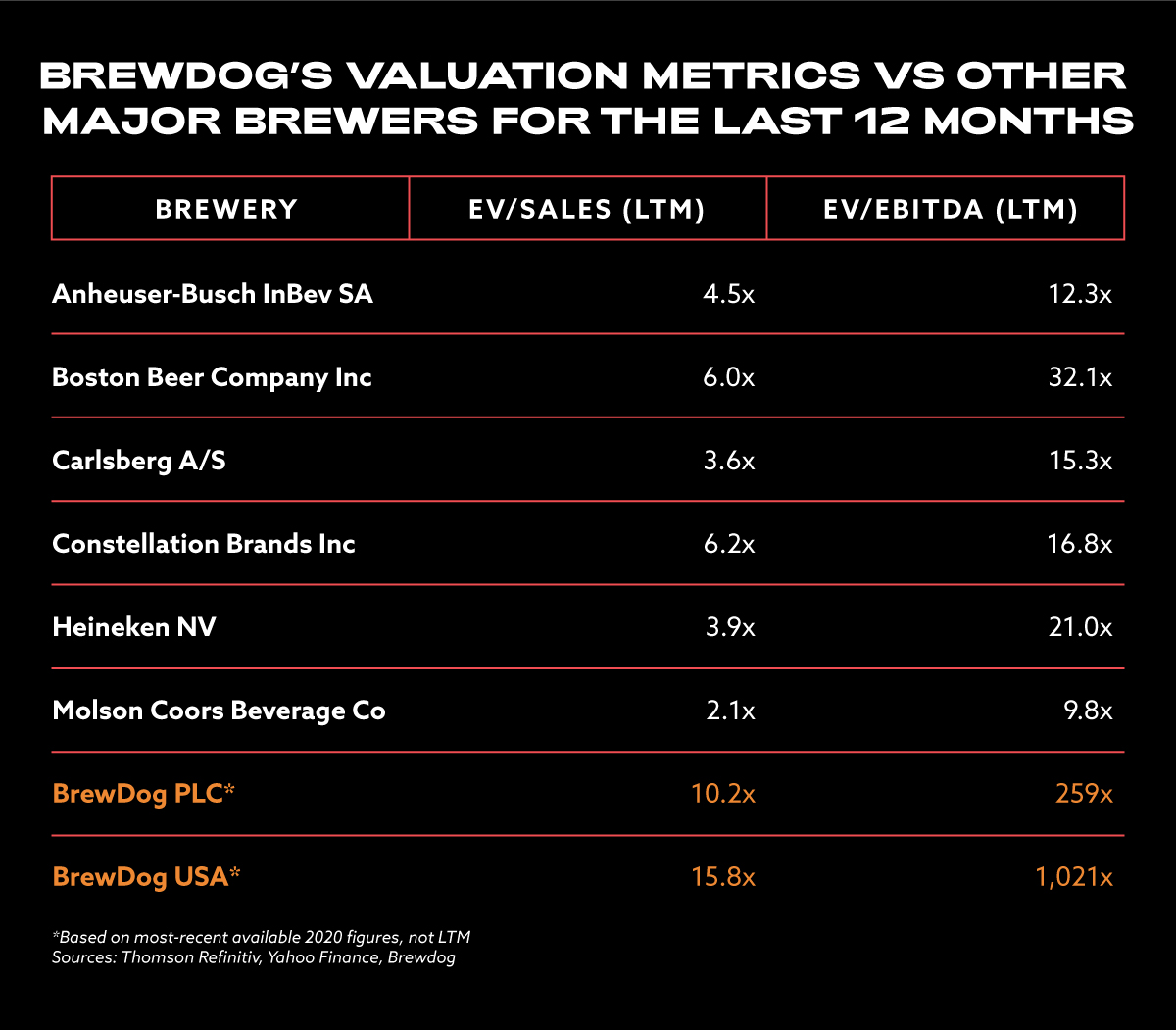

Simply put, the firm’s valuation metrics are out of whack when compared to those of brewers around the world. In its current EFP round, BrewDog plc claims to be valued at around £1.88 billion — over 10 times its net revenue in 2020 (£182 million.) For comparison, top global brewers like Anheuser-Busch InBev, Heineken, and Molson Coors typically trade around three to six times their net revenues.

Comparing BrewDog plc by another metric, EV/EBITDA, yields similarly head-scratching results. (For those unfamiliar, this acronymic jumble stands for the ratio of a firm’s enterprise value [EV] to its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, or EBITDA — a rough proxy for a firm’s operating cash flow.) At an enterprise value of £1.88 billion, the Scottish firm’s trailing EV/EBITDA would be 259x, according to figures from its 2020 annual report. Even Boston Beer Company, which is red-hot these days thanks to the runaway success of Truly hard seltzer, has traded at an enterprise value of just 32.1x EBITDA over the last 12 months.

To be fair, private companies are notoriously tricky to value, and these brewers are all bigger and more efficient than BrewDog is at this stage. But they are also the companies that Watt wants to be compared to. “Our goal is to build the world’s leading beer brand,” he told Fortune in May 2021. “This is about outselling Heineken, and that’s always been the aspiration.” To pull that off, BrewDog will have to deliver more massive growth, more efficiently in the face of post-pandemic reopening challenges and more competition than ever. As one industry consultant told The Financial Times in a June 2021 story about investors’ growing discontent with the brewer’s handling of its worker-treatment scandal: “BrewDog is now a large business and craft beer is maturing — it’s no longer the explosive growth category that it once was […] So achieving that valuation is going to become increasingly challenging.” The paper reported that BrewDog’s net revenues grew just 4.2 percent in 2020 (down from 25 percent growth in 2019), and that the company booked a loss of £7.4 million overall for the year.

If BrewDog’s growth slows down, its punks — some of whom were unaware of TSG’s looming position, according to The Financial Times’ report — may pay the price. Unless the company’s value outpaces the guarantee it promised TSG, equity punks stand to lose money at a public listing, because BrewDog would have to dilute their shares to pay that 18 percent compounding return. As the newspaper notes, “newer investors risk making nothing or losing money even if the company’s value rises.” By the end of the year, Ostrow calculates, BrewDog plc would have to go public at £1.89 billion or higher for new equity punks to break even.

Whether it could command such an eye-popping figure is anyone’s guess. But for some context, Constellation’s famously frothy $1 billion acquisition of Ballast Point valued that craft brewery at just under nine times its trailing revenue with a projected future EV/EBITDA in the “mid-to-high teens.” The valuation BrewDog plc must aim for in any 2021 IPO to keep new punks whole is over $2.6 billion — more than double Ballast Point’s 2015 price tag, with metrics that suggest it is more overpriced now than the San Diego darling was midway through last decade’s craft beer salad days. (Infamously, Constellation sold Ballast Point, just a few years later, reportedly for dimes on the dollar.)

And remember, thanks to the private-equity elephant in the room, the longer BrewDog waits, the more it will owe, and the bigger its IPO must be to save incoming investors from dilution. The brewer could come up a billion pounds short of its targeted listing, and TSG would still get paid. But the punks… well, as one investor noted on the EFP forum in March 2021: “If BD’s valuation is falling behind the TSG curve then the best time to IPO is yesterday.” On the flip side, a surprisingly splashy IPO is not out of the question for BrewDog plc, and in that case U.K. punks and TSG (which these days also owns around 900,000 Common A shares) would both win out. But it’s hard to see a similar path to profit for their U.S. counterparts.

“Rapid growth with minimal downside”

When Jason Block took the reins of BrewDog USA in January 2020 as the company’s third CEO since 2019, filings indicate his compensation package included stock in BrewDog plc (the parent company) rather than BrewDog USA, the company whose performance he is responsible for managing.

Why? A plausible explanation is that shares in BrewDog USA Inc. — a completely separate company that is nearly wholly owned by the Scottish parent firm — simply aren’t very valuable, and won’t be for the foreseeable future. “Even if the [BrewDog USA] equity was worth something, they would have to give [Block] a ridiculous number of shares” to properly compensate the executive, speculates Apsara’s Ostrow — which, when disclosed, could cast unfavorable light on the true value of the U.S. subsidiary as a whole.

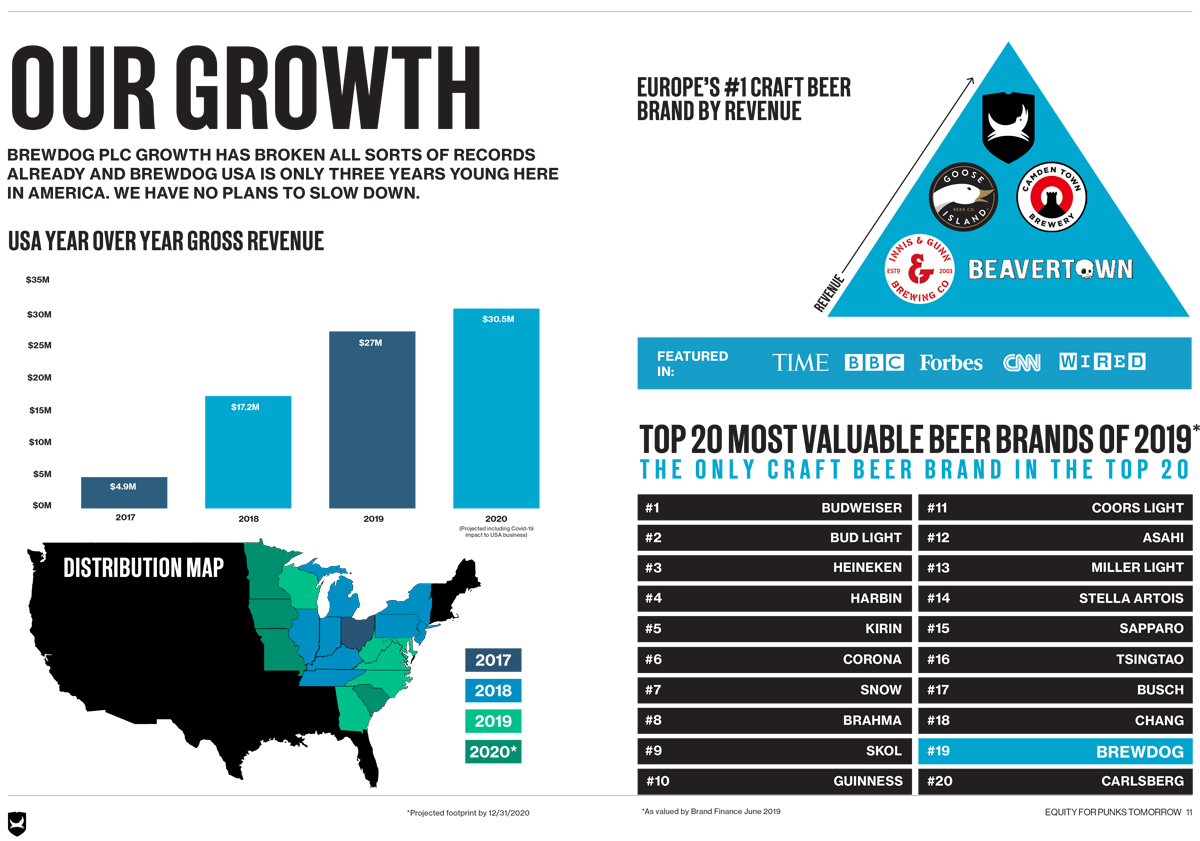

Do regular-Joe beer-drinkers who get served a BrewDog Facebook ad about “own[ing] your own brewery” understand the distinction between the plc and its U.S. subsidiary? Again, it’s not a secret: Everything is disclosed in the EFP prospectuses of both parent and child. But those materials are difficult to parse for lay people, and throughout them, the company also prominently associates the Scottish firm and the U.S. offshoot, to the extent that a reader unsavvy to the companies’ transatlantic relationship could be forgiven for seeing no daylight between the two. “BrewDog plc growth has broken all sorts of records already, and BrewDog USA is only three years young here in America,” boasts one slide of the U.S. EFP prospectus. It shows growing year-over-year U.S. revenues (more on that in a moment) next to charts touting BrewDog plc’s more established bona fides.

If BrewDog plc does go public later this year, it’s not clear that BrewDog USA shareholders would benefit. Per the current EFP circular (a decidedly more dense, picture-free document the company is required to file with each U.S. crowdfunding round), though the subsidiary and plc are discussing ways to let American equity punks get in on the latter’s rumored listing, “[p]otential investors in this offering should not rely on or expect any such IPO to take place, or expect to benefit in any manner from such an IPO should it take place.”

“I read [that clause] as ‘don’t get your hopes up because it would take a special agreement,’” muses Ostrow. “What motivation do they have to do that?”

Who knows! What we do know is that for $60 a share, American punks get whatever perks they’re able to wrangle from BrewDog, plus equity in the U.S. business. But despite rising revenues, BrewDog USA is losing money, and indebted to the parent company that wholly owns it. The setup (as ever, properly disclosed if not widely publicized) seems to allow the Scottish firm and even Watt himself to draw money from the subsidiary as they see fit, with American punks paying for the privilege of offsetting their risks.

Founded in 2017, BrewDog USA consists of an Ohio brewery and a constellation of bars and facilities across the American Midwest, with more locations in the works. On the surface, things seem to be going well. In 2020, the same year it launched its current EFP crowdfunding round, it made its debut on the Brewers Association’s top-50 list of craft breweries by sales volume at No. 41. Based on the $60 share price in the current EFP crowdfunding raise, the U.S. subsidiary is valuing itself at around $391 million; including debt, its enterprise value is closer to $432 million. But the U.S. subsidiary’s total sales in 2020 were around $27.2 million, making its enterprise value around 16 times its revenue. (Ostrow calculates its EV/EBITDA ratio for those trailing 12 months at 1,021x, a figure “almost too comical to say out loud.”)

To look at it another way, if BrewDog USA valued itself at the same revenue multiplier as Boston Beer Company, one of the most popular, diversified, and high-performing U.S. craft breweries of the past few years, it would trade at an enterprise value of around $160 million. But if the subsidiary was acquired or went public at that price, new U.S. equity punks would lose about 70 percent of their investment, while earlier American punks would still stand to lose over half their capital. Now remember that BrewDog USA claims to be over twice as valuable as BBC based on revenue. “It’s just a really bad situation for those punks,” says Ostrow.

It gets worse. Over $40 million of BrewDog USA’s debt lies with BrewDog plc, which also owns around 97 percent of BrewDog USA’s shares. The arrangement is favorable for the Scottish parent: It allows the brewer to grow its footprint in the U.S. while maintaining a tight claim on the subsidiary’s assets and operations, all while selling shares to American drinkers for over $10 million in cash (so far) that can be flowed across the Atlantic as debt repayment. In 2020, records show, the U.S. subsidiary repaid the plc $1.27 million net, and did net negative $2.68 million in income.

“They’ve set up the structure for [BrewDog] USA to allow for pretty rapid growth with minimal downside to themselves,” says Ostrow. If the American subsidiary succeeds with its ambitious continued expansion into the crowded, maturing U.S. craft beer market, BrewDog plc’s growth gamble pays off and American equity punks’ illiquid shares at least remain whole. But if, worst-case, BrewDog USA fails, the parent company (by virtue of its near-total control of the firm) can bankrupt it, taking ownership of its assets and wiping out its U.S. investors in the process. Heads everybody wins, tails American punks lose.

Maybe most troubling (and least punk), Watt appears to leverage BrewDog plc’s control over the U.S. company, and his prominent position in both organizations, to enrich himself personally. First reported in the February 2020 print edition of British magazine Private Eye, the BrewDog co-founder is the owner of several companies in the U.S. that have entered into real estate deals with BrewDog, BrewDog USA, or associated companies.

For example, the circular accompanying BrewDog USA’s current EFP round shows that Watt wholly owns an LLC named Ten Tonne Mouse, which in turn wholly owns BrewDog Franklinton LLC, which leases bar space to the U.S. subsidiary in Columbus, Ohio. Watt, via these LLCs, had acquired the bar for $657,816 from BrewDog USA itself in December 2017 “with no gain or loss recorded for tax purposes.” Records show the building was purchased for $475,000 just nine months prior. In other words: BrewDog USA appears to have bought the bar, improved it, and quickly sold it to Watt, who began charging the company $12,500 per month to rent it under a five-year, $150,000-per-year lease. That’s a sweet 23 percent annualized return for the BrewDog cofounder, paid for by the U.S. company and its shareholders.

“It’s not suggested that any of these transactions are illegal or improper,” wrote Private Eye, which also found similar deals between Watt-owned LLCs and BrewDog plc. “The question is whether they are appropriate for a company with 100,000 other shareholders.” (In its latest annual report, the plc claims double that number of punks.) BrewDog declined to address VinePair’s inquiry about Watt’s real estate deals, and declined to explain them to The Financial Times, telling its reporters only that they were “tangential.” But Ostrow offered another potential explanation: “It just seems to be a transfer of value from [BrewDog USA] and its shareholders to Watt.”

BrewDog’s “Tomorrow”

In late June, as this story was being edited, BrewDog found itself in the headlines again. This time it was because the brewer had issued, Willy Wonka-style, a handful of “solid gold” beer cans that, upon closer inspection, turned out to be made mostly of brass and likely worth only a fraction of the value it had advertised.

Promoting something that looks like an asset that under scrutiny winds up being nothing more than an overvalued gimmick designed to part credulous fans with their beer money? As far as metaphors go, it’s pretty on the nose. But subtlety has never been BrewDog’s strong suit.

The “gold can” scandal drew attention from the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Agency; that regulator’s review joins one over BrewDog’s B-corporation certification on the list of oversight actions the brewery triggered in June alone. They’re the most recent signs that the disparity between how the company markets itself and how it actually behaves may result in consequences for its business.

But how long will that reckoning last? Watt, who walked back his initial response to the scandal with a statement accepting responsibility for failing his former workers, remains in control of BrewDog plc along with Dickie thanks to the pair’s shares (though due to the outrage over Punks with Purpose’s letter, a TSG exec now chairs the brewery’s board). With an IPO rumored for later this year, bars reopening in the U.S. and U.K., and TSG’s entitlement growing all the while, there’s plenty of reasons to “hold fast,” as Watt himself likes to say — to plow ahead with the plan in hopes of putting the latest scandal in the rearview and beating out the private equity firm’s bite with a mammoth listing.

Whether the company can win that race and turn EFP brass into IPO gold remains to be seen. But even if “the Good Ship BrewDog,” with Watt at its helm, can pull off that kind of financial alchemy while navigating its latest crises and a shifting market, American investors may still find themselves… well, punked.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!