Last year, demand for Oatly, a Swedish oat milk popular at third-wave American coffee shops, outpaced supply. National shortages ensued. Oatly superfans were devastated, and apparently willing to spend $25 per 32-ounce carton on Amazon.

It’s tempting to write this off as a fluke or embarrassing display of disposable income. But the alternative milk industry has become a true juggernaut — too economically and culturally significant to ignore.

The number of creamy, coffee-adjacent beverages on supermarket shelves and in baristas’ arsenals is growing. In addition to cow, sheep, camel, and goat milks, others made from coconuts, peas, rice, soy, oats, and an array of tree nuts have arrived to entice and confound consumers.

Our cups and the market runneth over. Almond milk sales reportedly surged 250 percent from 2011 to 2016. Cow’s milk is in a “decades-long slump,” according to Supermarket News, but it still comprises 90 percent of milk sales. Meanwhile, alternative milks jostle for position. Some market researchers predict the overall alternative milk market will surpass $34 billion by 2024.

Having so many new options introduces a gallon of important questions. Does one alternative milk taste the best? Are they all expensive? Is almond milk terrible for the environment? Or is that cow’s milk? Which is the healthiest?

It’s never been more difficult to be a conscientious consumer, especially with so many competing priorities. We have access to endless information, but we often can’t verify it. Rules, regulations, and recommendations change constantly. A nutritional or environmental study published in 2013 might be invalidated by 2016. Opaque food conglomerates unveil new products at a startling clip.

All you can do is arm yourself with as much information as possible and make the right decision for you. This definitive guide to the completely undefinable world of milk is one step toward separating the oat from the chaff.

Nothing is black or white in 2019. Not even milk.

The Rise and Fall of Soy

“We took out soy when we found oat milk,” Steven Sutton, founder and CEO of Devocion, a coffee shop with locations in Brooklyn and Manhattan, tells VinePair. “And now it’s going crazy!”

Blue Bottle, the Oakland, Calif.-based coffee chain majority-owned by Nestle, also recently swapped soy for oat milk. They are part of a larger consumer shift away from soy in our ongoing search for the perfect milk.

Soy milk, our first alternative-milk crush, hit the U.S. mainstream in the late 1990s, when a medical study linked it to cardiovascular health. Americans embraced it with a convert’s zeal. By 2008 we were spending $1.2 billion on soy milk.

“There were all kinds of other health benefits attributed to soy,” Nadia Berenstein writes in Serious Eats. “It was supposed to reduce the risk of breast and prostate cancers, protect bones against osteoporosis, temper the symptoms of menopause, and supercharge weight loss.”

By 2015, however, sales had dipped to less than $300 million. New studies had raised health and environmental concerns. (“Is this the most dangerous food for men?” reads a 2009 Men’s Journal headline above a mountain of soybeans.) (It’s not.)

The damage was done. By the late aughts, conscientious consumers had started associating soy milk with unnecessary sugars, hormone imbalances, GMOs, and monocultures decimating the American Plains.

“There is concern about ‘anti-nutrient’ substances naturally found in soy, like phytic acid,” Joy Stephenson-Laws, founder of pH Labs, a national health nonprofit, writes VinePair in an email. “Phytic acid can make it difficult for the body to digest certain important nutrients, like magnesium, copper, iron, and zinc.”

Still, soy milk is not the black sheep we once imagined.

“Of all the alternative milks, soy milk has the highest protein content,” Stephenson-Laws says. “It is a good source of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids which are usually good for cardiovascular health.”

The sugar content of soy milk depends on the label, and most brands offer unsweetened options. The ecological impact of soybean farming also varies enormously. Some commercial farmers are exploring new methods to better protect soil health.

“I have nothing but sympathy for American consumers who have to do so much research to figure out if they’re buying something ecologically sound,” Eve Andrews, who writes the Ask Umbra column for Grist, says.

Almond Joys

Before long, almond milk was starring in our hearts, minds, and latte art. From 2010 to 2015, Americans spent twice as much on almond milk than all other alternative milks combined, according to Nielsen data.

Almond milk appeals because it tastes familiar — the average American casually ate more than two pounds of almonds in 2012 — and is rich in vitamins and heart-healthy fats. Unsweetened varieties are less caloric than soy or cow’s milk, too, Stephenson-Laws says.

On the flip side, almond milk has less protein than cow’s or soy milk, and a lot of people have nut allergies.

It’s also got a really bad environmental reputation. “Lay off the almond milk, you ignorant hipsters,” Mother Jones titled a widely shared 2014 story in which correspondent Tom Philpott calls almond milk “an abuse of a great foodstuff.”

Philpott rattles off a laundry list of almond-related abuses, including how it takes 1.1 gallons of water to grow one almond, and that 80 percent of the world’s almonds are grown in drought-ridden California. Almond milk is more expensive per ounce than unadulterated nuts, Philpott says, but it has a fraction of the nutrients. Commercial almond milk has additives and stabilizers. Almond milk doesn’t love you, and never will.

It’s true that almond farming is terribly water-intensive, but industry analysts raise a counterpoint: A relatively small amount of almonds goes into each cup of almond milk.

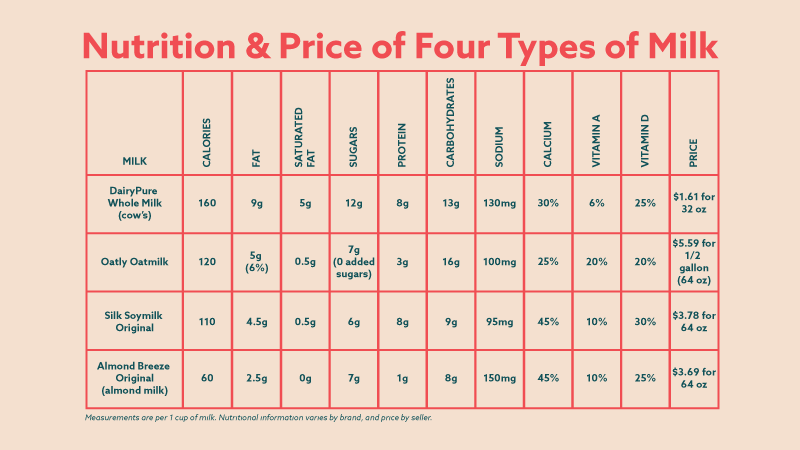

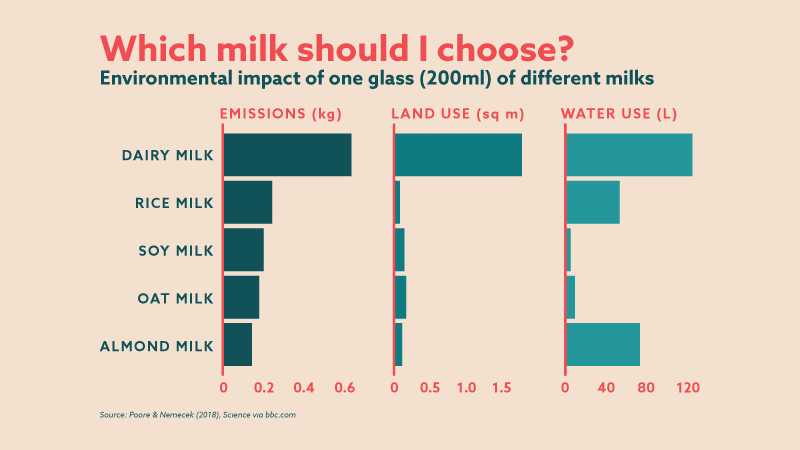

“Per cup, almond milk is less water intensive than cow’s milk,” Emily Cassidy, now a data journalist at The World Resources Institute, wrote in 2018. It takes 10 gallons of water to produce one cup of almond milk, and 64 gallons to make a cup of cow’s milk. Oh, and drought-addled California is the top dairy-producing state in the U.S.

“Cow’s milk is always going to be more environmentally intensive than plant milk because you have to raise a cow and its food,” Andrews tells VinePair.

In addition to water, cows require land, fertilizers, and pesticides (which can also contribute to global warming). A byproduct of cow manure is nitrous oxide, “a climate-warming pollutant 298 times more powerful than carbon dioxide,” according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“The fact is that dairy agriculture produces a lot of methane and plant-based agriculture doesn’t,” Andrews says, “and the atmospheric methane situation is pretty serious, and looking worse by the day.”

Hello, Oats

Oat milk, the newest alternative milk du jour, has a lot going for it.

“Oat milk is delicious,” Stephenson-Laws says, adding that oats can lower cholesterol and blood glucose levels, and may contain anticarcinogens. Very few people have oat allergies or trouble digesting them.

Oatly, those Amazon users’ beloved brand, has no dairy, gluten, soy, or GMOs. According to Oatly’s 2017 sustainability report, it “generates 80% lower greenhouse emissions than cow’s milk. Land use is also about 80% lower.”

Of course, nothing is perfect. Oatly is “comparable to other milk alternatives in terms of sugar content,” Bonnie Wertheim writes in The New York Times, “but relatively high in carbohydrates and calories, with about double those that a serving of almond milk contains.”

It’s also far less nutritious than cow’s milk, which contains all amino acids required by the human body, Stephenson-Laws says, plus calcium, magnesium, potassium, riboflavin, folate, protein, and vitamin B12.

“You can’t really compare cow’s milk to plant-based milk,” Stephenson-Laws says. “If you are hoping to drink plant-based milk and get the same benefits as cow’s milk, this will not happen.”

To Thine Own Milk Be True

Ours is a nation weaned on superstores, and fashion that promises to take us day to night. We want one-stop shopping for peak nutrition and environmental responsibility. We want it to taste great and be affordable. Unfortunately, there’s no one milk that fits all.

“It depends on your value systems,” James Hamblin, staff writer at The Atlantic and author of “If Our Bodies Could Talk,” says. “If you worry a lot about optimizing your health, and it’s going to actually give you a good feeling to know that you got a slightly better fat-to-carb ratio in what you’re taking in, and you genuinely get value from it, that’s one thing.”

If, on the other hand, you care most about how your milk tastes, or how frothy your cappuccino gets, that’s another.

“I don’t think there’s a clear health recommendation for any one unless you have a specific dietary reason you need to avoid something, like lactose,” Hamblin says. “Or if you have an ethical problem with the farming of animals.”

If, on the other hand, you adore cow’s milk but are concerned about its environmental footprint, you can incorporate other climate-conscious choices in your life, Andrews says. Driving less, say, or eating less meat.

Just like the people who produce and consume it, milk contains multitudes. Sadly, Got nuance? doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, though.