This article is a part of our Matters of Taste series, essays from our favorite writers on the artifacts and abstractions they hold most dear in their drinking lives.

As I write this, I’m sipping a vodka-soda from the finest lowball glass I have ever owned, which may be among the finest ever made. Given these superlatives, you’ll be surprised to learn that it’s also a souvenir glass, obtained “free” with the purchase of the trademark drink served in it. Lest you think such an item unrefined, consider that it’s perfectly proportioned, with nice, thick glass — just a bit wider at the top, with a solid base that assures it won’t knock over easily. Painted along the sides are palm trees and a gazebo-like building on stilts, ocean surf rolling below.

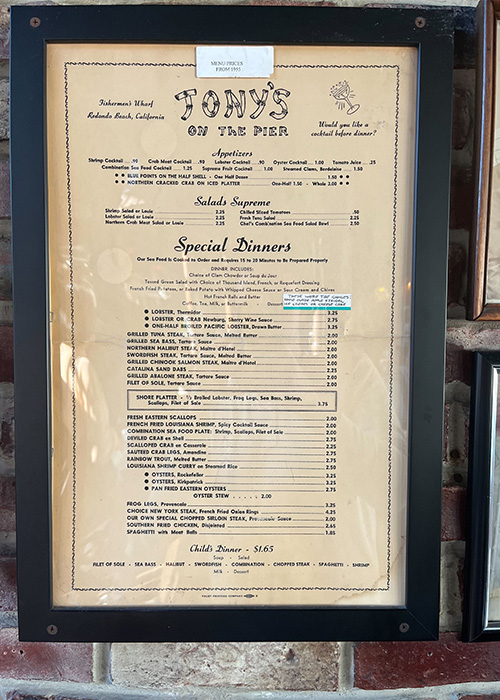

This, as the glass informs in midcentury script, is Tony’s On The Pier, a restaurant and bar in Redondo Beach, Calif. Affectionately known as Old Tony’s, it remains a crown jewel of beachside kitsch, crowded by tourist shops of all description, and advertises the “BEST” seafood of Los Angeles County’s South Bay region. In addition to the main bar and dining room, which allow guests to watch the tide roll in while feasting on a platter of scallops or coconut shrimp, there is a second, octagonal level, or “crow’s nest,” with a shingled roof and panoramic, 360-degree views. Freely flow the grooves of live guitar during happy hour, though the greater draw by far is the clear vantage of the western horizon where, more often than not, the sunset dazzles before it slips into the Pacific.

What else could tie this scene together but a tropical beverage? Tony’s has just the thing: a widely renowned, old-school Mai Tai, poured into a glass just like the one I’d bought. By the time the establishment turned 65 in 2017, the owners estimated they’d served around 7 million of the beloved tiki drinks. (And who knows how many since then?)

But I didn’t know any of this when I found the glass — or “my” glass, as it became in the home I share with my partner fewer than 25 miles from Tony’s, yet a clichéed journey in traffic between here and that vintage, shoreline paradise. The object itself I discovered in a nearby West Hollywood thrift shop, noticing a vessel so charged by nostalgia I wondered how anyone had managed to give it away. I bought it for only $3, or $5 at most, and ceased to drink cocktails from anything else. It gave me warmth from a wonderful place I’d never seen, while being roomy enough for two extra-large ice cubes.

In my pessimism, I imagined Tony’s already gone. Southern California can be indifferent to its landmarks, if not downright hostile, and the fuzzy feeling I got from my favorite new cabinet fixture was delicate. How could I accept that such a haven had vanished, or fallen into ruin, before I was able to visit? Nonetheless, I showed my treasure to a friend, a preservationist who grew up in L.A. She texted back that Old Tony’s was still standing and worth the trip. “I live to recommend restaurants that opened before I was born!” she replied once I thanked her for the vote of confidence.

People here are always baffled to learn that I grew up in the Northeast; that’s how well I’ve assimilated, thanks in part to a collection of colorful tank tops. Tony’s had shot to the top of my “Classic California” must-do list as a venue where I figured the radiant energies of my adopted home were strongest, this dream of an idyll on the edge of the world almost believable. A month later, following a Sunday outing to Rat Beach (don’t worry, it means “Right After Torrance”), we had our chance to confirm. The Redondo Beach Pier was bustling with families — a Father’s Day crowd — and the wait for a table at Tony’s was at least 45 minutes.

Isn’t that the time we’re meant to fill with a cocktail? It’s as if they’d thought of everything. We had admired the tacky neon sign outside, and, indoors, felt at home under fishermen’s nets draped from the ceiling. We studied the wall of autographed photos from guests including Barbra Streisand and Johnny Carson. It was a fine hour to chat, taking in the friendly ambiance while listening to waves pound the wooden landing that held us above their thrilling force. We ordered those famous Mai Tais in view of a wooden sign boasting “Have a Mai Tai / Over one million served.” The numeral “7” had been written over the word “one,” a charmingly thrifty renovation. And we had the pleasure of adding ourselves to those many happy customers: The drink itself is an alchemical triumph served on crushed ice, neither too boozy nor oversweet, a maraschino cherry for garnish.

Even better, the glasses were updated to commemorate a jubilee year. The new design used white paint, while additional text read: “70th Anniversary / 1952-2022 / Thank You.” Looking for history, I’d found more of it than expected.

https://twitter.com/MilesKlee/status/1538934662885625856

The rest of the summer, I ordered Mai Tais anywhere they appeared on a menu, hoping for a version so balanced and pure, so quintessentially itself, that it took me back to the golden reverie before our meal at Tony’s. Of course I was disappointed, again and again, by the ordinary L.A. bars — their tropical beverages were sloppy and saccharine, fit only for a college basement party. I’m willing to admit that the blissed-out surroundings influenced my estimation of the Tony’s Mai Tai, but in truth, the appeal of the rum drink and its natural environment are exactly the same. Both represent the epitome of formula, something elemental and immutable. It works, it has been perfected, and you simply never change it.

Or maybe it’s the glass itself, a heightened expression of boozy leisure, that really transports me. As we paid the tab for dinner at Tony’s, the attentive waiter saw we had every intention of taking our tumblers home as souvenirs, and he wrapped them beautifully in paper napkins. I remembered the care he’d taken when, a week later, the Tony’s glass I’d found in a secondhand store slipped out of my fingers and shattered on the kitchen floor, leaving us with the pair we’d earned on our pilgrimage. The past can be a rosy idea, but our grasp on it is never sure.