Italian wines can be confusing and Italian wine law can be even more confusing. Yet Italian wine is some of the most popular wine on the American market and because of this, the Italians will change their laws more often than many other wine producing countries in order to accommodate what seems to be popular, while outlawing wines that have fallen out of style.

The newest legal development in the world of Italian wine? You’re about to see a new wine label from the Chianti hills. Do we feel a disturbance in the Force? We have yet to see, but I am going to try to make this new development as clear as possible. If you are still confused after this post, leave a comment and I will be happy to help further.

Chianti, in Tuscany, is one of the most famous wine regions in the world. Even if you aren’t all that familiar with Italian vino there’s a good chance you’ve seen Silence of the Lambs or at least the iconic scene when our boy Hannibal lecter delivers his monologue about having a disagreement with a census taker and how he, “ate his liver with some fava beans a nice Chianti.”(FttFttFtt).

Although we know the name, do we know what the region and its wine is all about? To give you an idea of how big the Chianti appellation is, it takes up the majority of the Tuscan region – that’s a huge amount of space. It’s so big in fact that it overlaps smaller DOC’s and DOCG’s allowing them to make Chianti if they want in addition to their own regulated wine. WHOA!

But Chianti wasn’t always this big. It all started in the humble rolling Chianti hills just south of Florence, consisting of six townships with varying soils and climatic influence (terroir) that produces blends from local grapes such as Sangiovese, Canaiolo and Colorino. Over time these wines became popular on a mind boggling level, due in part to the region’s proximity to Florence, the epicenter of Italian culture, but also because the wine was very good. In the middle ages the British even had a nickname for it, Chiantishire.

In the 1800’s there was this dude Baron Bettino Ricasoli who, after years of experimentation, decided that Sangiovese was the ideal grape to framework the Chianti blend. The Baron was not only a dedicated agriculturist but was also a dominant political figure who would become the second prime minister of the newly unified Italy in 1861. Ricasoli’s blend soon became the norm and in the 1960’s when Italy had developed its new appellation system (DOC, DOCG, awarding Chianti it’s designation in 1967, the Ricasoli formula was all the rage and it was formally made into the DOC law. But this law also allowed white wine grapes into the blend which was a recipe for disaster.

Over time this large region enjoyed even more success on the American market, until the 70’s when production demand meant using more white wine grapes, thereby diluting the quality. It was a messy time in Chianti, prompting winemakers that were ashamed of the watered down perception to make wines outside the law. Super Tuscans were born. The almost instant popularity of this style overshadowed the Chianti region, leading to an upgrade in 1984 from DOC to DOCG which restricted the laws, doing away with the white wine situation and bringing birth to a new era of quality wines getting more exposure.

It wasn’t just these rebels that were upset. In part, because of the glut of thin juice, winemakers in the original Chianti zone made up of the six original townships decided they needed to disassociate themselves from the larger DOCG. This Classic zone had operated under it’s own set of rules since the 1930’s and they wanted to capitalize on the uniqueness of the area. And so, in 1996 The Chianti DOCG zone was awarded a separate DOCG sub zone, Chianti Classico, encompassing the six original townships located in the rolling Chianti hills.

Since then Chianti Classico has had two levels of wine, Chianti Classico, aged for 12 months before release and Chianti Classico Riserva, aged 24 months before release. In 2006 the Classico region also did away with the white wine ratio, removing white wine from the Chianti blend for good. And so here we are with wines that can be a minimum 80% and up to 100% Sangiovese, while still allowing for other native grapes like Canaiolo and Colorino as well as classic Bordeaux varieties Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot to be blended in as well.

But Classico was still not happy. They wanted a way to highlight specific terroirs. Would they go the way of Burgundy and develop Crus? No, not the Italians. Classico wanted more focus but creating crus was somehow just not on the agenda. Instead they decided to focus on their current two tier quality level and tweak it a bit. They started talking about it in 2011 and as of 2014 we now have Chianti Gran Selezione to add to the mix.

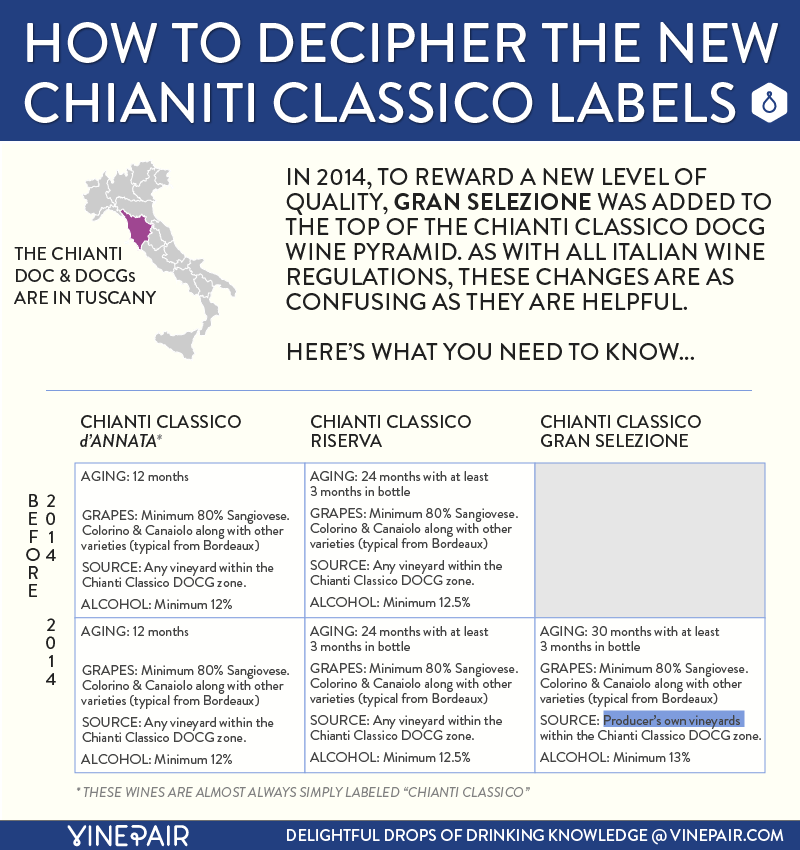

Italian wine laws are crazy, just as we start to understand them they change in front of our eyes. If Chianti is a favorite of yours, you are about to see a new Chianti designation on wine lists and wine shop shelves, so I thought I would let you in on the secret. This new arrangement of quality is supposed to focus on terroir but to me it’s looking more like a marketing scheme to sell more Chianti. Since this new designation has just been put into law we’ll have to see how terroir-driven future vintages will actually taste, as most of the current slew of awarded Gran Selezione wines were vinified before the law was put into place. Here’s the new breakdown both in graphic and text form:

Here’s what the original Chianti rules used to look like:

Chianti Classico:

- Minimum of 80% sangiovese with the allowance of other native grapes Colorino and Canaiolo as well as Bordeaux varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

- Minimum aging requirement: Minimum of 12 months with at least 7 months in oak.

Chianti Classico Riserva:

- Minimum of 80% Sangiovese with the allowance of other native grapes Colorino and Canaiolo as well as Bordeaux varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

- Minimum aging requirement: Minimum of 24 months with at least 3 months in bottle aging.

Simple right? Doesn’t seem to need a reformation does it? There are other aspects to these laws but I don’t want to get too geeky as you are just trying to enjoy the wine.

Here’s what the new rules look like:

The new tweak is mostly about grape source and aging. The allowed varieties stays the same.

As of 2014 there are now three types of Chianti Classico:

Chianti Classico Gran Selezione:

- Grapes must be grown by the winery itself

- Minimum aging requirement: 30 months, including 3 months of bottle aging.

Chianti Classico Riserva

- Minimum aging requirement: 24 months, including 3 months of bottle aging

Chianti Classico d’Annata (meaning yearly wine)

- Minimum aging requirement: 12 months.

As you can see much stayed the same while allowing for the low end to be more approachable and the high end stricter and more focused.

The takeaway from all of this for the consumer is that Chianti Classico really wants you to see them as a separate entity from the larger zone surrounding it. Where they used to promote only the highest of quality, now they want you to know that not only do they have terroir driven wine but they can give all levels of quality within one small romantic subzone.

If this still sounds confusing imagine how it looks in a wine shop. In the Italian section there would be a Tuscan section. Within that Tuscan section there would be a shelving unit dedicated to Chianti. The unit would be split into two parts. Let’s say it has six shelves. The top half would be for the Chianti Classico DOCG wines which would have three levels of quality. The top shelf would house the Gran Selezione and would have higher price points. The next shelf would house the Chinati Classico Riserva, which may have the same price points as the top shelf. On the next shelf would be the Chianti Classico D’Annata, with prices in the more moderate range. The last three shelves would be dedicated to wine made in the larger Chianti DOCG, but not associated with the classico zone.

It’s a lot to digest, but now you know what Gran Selezione means the next time you see it on a wine list or shop near you. And you can decide whether to purchase it, or a Riserva of basically the same quality.