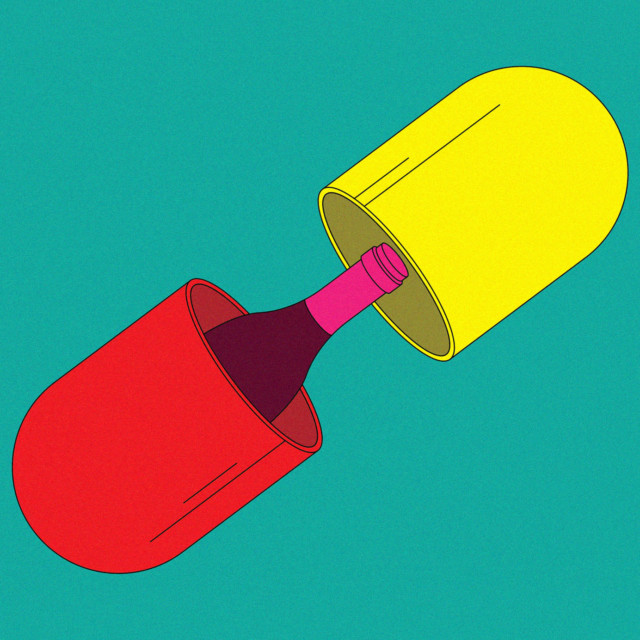

Feeling lethargic and in need of a pick-me-up? There’s a type of wine for that. Or, at least, there was. In the English-speaking world, there’s a long tradition of plugging “tonic wines” to give drinkers a little boost. These so-called tonic wines claimed to offer health benefits and rejuvenate drinkers, either thanks to special added ingredients, or due to the naturally occurring properties of grapes as a result of their terroir. These wines were popular in Britain until the second half of the 20th century, by which point their medical claims no longer stood up to scrutiny.

People have both prescribed and used wines as medication for thousands of years, but with advancements in scientific methods over the 18th and 19th centuries, doctors and wine marketers became more precise in how they described their respective offerings. For example, in the 1860s, a British doctor named Robert Druitt published a book prescribing particular wines for different ailments. He thought light Bordeaux wines were especially good “for children, for literary persons, and for all those whose occupations are chiefly carried on indoors, and which tax the brain more than the muscles.” It’s safe to say that today’s office workers and freelance writers would probably agree with him.

Wine, Your Daily Multivitamin

Long before scientists noted red wine’s potential cholesterol-lowering properties, the drink was enjoyed as a supposed source of vitamins and minerals; In the 18th century, the British Navy supplied its ships with red wine for long voyages with the belief that fruits and vegetables warded off scurvy. We now understand that vitamin C prevents scurvy, but red wine doesn’t retain the vitamin C that’s found in fresh grapes.

Similarly, from the 1920s through the 1950s, one of the major importers of Australian wine into Britain advertised its red wine as a “natural tonic” because its grapes were grown in “ferruginous soil.” There’s no evidence that iron-rich soil results in iron-rich wine, but the discovery of vitamins and the popularization of nutrition science in the 1920s made this a trendy advertising angle. By the 1950s, some wine importers worried that this advertising strategy had backfired, and that Australian wines were associated in Britain with anemic old ladies.

Not a Vegetarian Option

There’s pairing red wine with meat, and then there’s spiking a red wine with meat. In 19th- and early 20th-century Britain, “meat wines” — usually ruby port wines fortified with meat, yeast, and malt extracts —were advertised for convalescent adults and children. Analysis by the British Medical Journal found that most meat wines were around 20 percent ABV. A typical dosage was three small glasses a day for adults and half for children. Meat wines were not produced in bona fide wineries but by British condiment manufacturers who imported wines to use as the base for their concoctions. These manufacturers included Colman’s of Norwich, famous for its strong English mustard, and Bovril, which sold a signature, eponymous meat extract for making restorative broth. Surprisingly, there is no evidence that the Australian industry ever produced a tonic wine by marrying its strong red wines with its beloved Vegemite, which was surely a missed opportunity to create a vegan market for tonic wines with more umami.

Blame It on the Bucky

Long before the Espresso Martini, and simpler than mixing a rum and coke, coca wines were another 19th century tonic that aimed to offer an immediate and powerful boost. Made with fortified red wine and coca leaf extract, these wines offered alcohol, caffeine, and cocaine in a single, sweet sip. Coca wine faded out of fashion by the 20th century as consumers became more alarmed at the effects of sipping cocaine, but its legacy lives on in Coca-Cola, which contains caffeine from the coca leaf, sans cocaine.

Most of these tonic wines ceased production by the middle of the 20th century, as nutritional science and food labeling caught up with the spurious claims of tonic wine’s producers. However, one unlikely tonic wine remains popular in Britain: Buckfast. Created by actual Benedictine monks in an abbey in southwest England in the 1880s, Buckfast is a fortified red wine with added caffeine (and a secret list of other flavorings). Initially a small artisan production, it now sees sales over $60 million a year and is particularly popular in Scotland and Ireland. Buckfast Tonic Wine now carries a disclaimer that it does not offer any health benefits, and its popular perception is quite the opposite of healthy. Relatively inexpensive, loaded with caffeine, and syrupy in flavor profile, the wine has proved an attractive combination for teenagers looking for trouble. In fact, Buckfast has been associated with so much anti-social behavior and violence. The empty bottle has been reused as a weapon, and “blame it on the Bucky” is a common excuse in arrests in Scotland.

It’s an unusual trajectory for a drink, from anemic patients to punk rockers, but it’s fair to assume that few people drank tonic wines solely because they enjoyed the taste. Tonic wines were sold in British pharmacies through the 1950s because they were considered medicinal — not because they tasted like cough syrup, although they probably did. They’re hard to find today, but that’s probably no great loss to the modern drinker. Some things are best resigned to history.