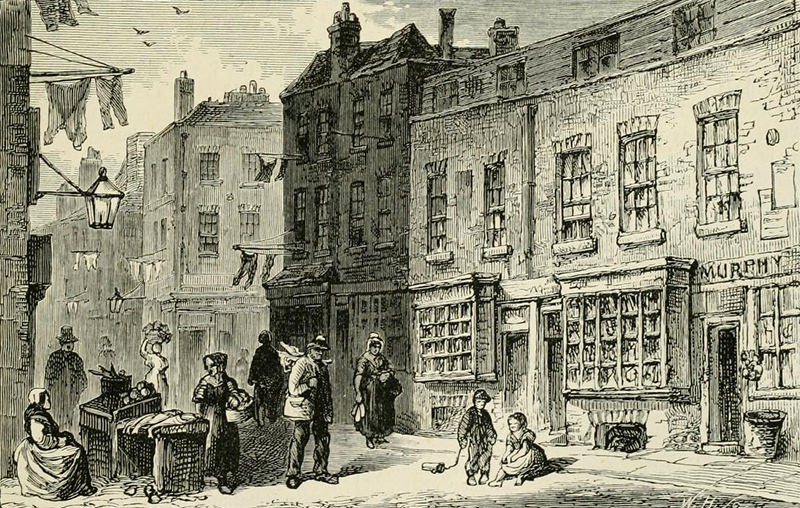

October 17, 1814 started as a day like any other in London. Most of the men in the parish of St. Giles, a poor working-class London neighborhood, were off to work. A group of women were holding a wake to comfort a friend who had just lost her two-year-old son, and a mother and daughter were having tea. And just around the corner, the brewery of Messrs. Henry Meux and Co. was brewing a batch of their acclaimed porter.

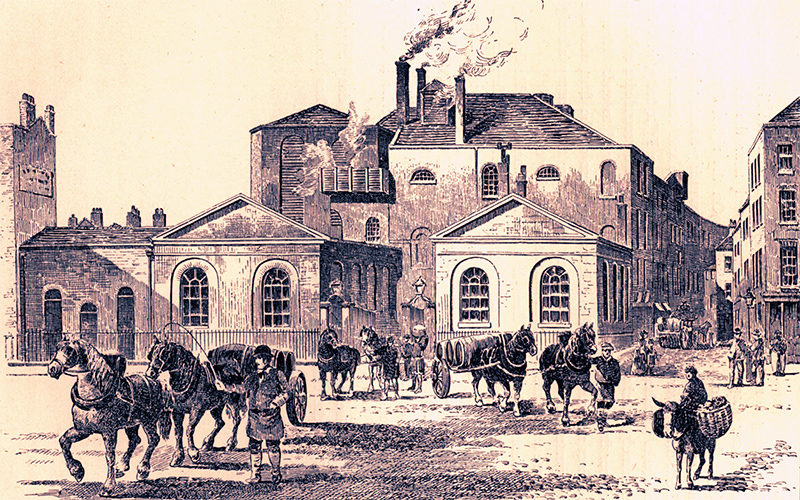

The Horse Shoe Brewery was founded in 1764 and quickly became a major producer of porter. Over the years it grew to become the fifth largest brewer in London, producing over 100,000 barrels of beer a year, passing through the hands of multiple owners. Henry Meux, part-owner of another brewery, purchased the Horse Shoe in 1809. Disaster would strike five years later.

On October 17, 1814, storehouse clerk George Crick was making his rounds in the brewery, inspecting how the fermentation was going in the most recent brew, when he noticed that one of the large 700 pound metal hoops that helped secure one of the wooden fermentation vats had slipped clean off the large barrel. There were 135,000 imperial gallons of beer inside the vat — nearly 1.3 million 16 ounce pints — so the fact that the barrel was missing one of its metal hoops was an issue. George Crick alerted his superiors.

The beer vats in question looked a lot like wine and whiskey barrels only they were much larger and these barrels not only had to hold the weight of all that beer, they also had to contain the ferocious fermentation activity that was going on inside. Fermentation isn’t a gentle occurrence, it can be incredibly violent as the yeast churns away eating all of the brews sugars, and this rumbling needs to be contained inside a sturdy vessel. It’s not wonder Crick was concerned.

But when Crick reported his observation to his superiors, they informed him that unfortunately no one was around that day to fix the fallen metal loop. On their own inspection, however, those above him weren’t as concerned as Crick and they suggested that best thing he could do was leave a note for his fellow employee so that he could fix the barrel when he returned to work the next day.

Only a few hours later, the barrel burst, sending the 135,000 imperial gallons surging through the brewery. This torrent of fermenting beer set off a chain reaction, the force and sheer momentum of the beer causing the other barrels in the brewery to burst as well. In total, more than 323,000 imperial gallons of beer went flooding out of the brewery and into the streets.

The first casualty was Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant who was scouring pots at a water pump on the other side of a large brick wall that was next to the brewery. The force of bursting beer caused the wall to topple, falling directly on top of young Eleanor.

Residents scaled tables and walls to get out of the way of the oncoming beer, but it surged forth, out of the brewery and into the street. The beer flowed down New Street and since the streets had no proper drainage, the liquid had no place to go except into people’s homes. That’s how thousands of gallons wound up filling the cellar of an apartment building, the same cellar where the women were holding a wake for a two-year-old boy. All sadly drowned.

It was in that same apartment building where a few floors above, the mother and daughter were having tea. As the beer entered the cellar, the foundation shook and the building collapsed, killing the mother and daughter as well.

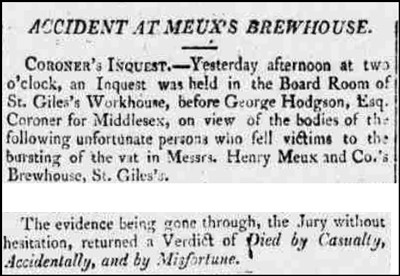

Eight people perished in what would become known as the London Beer Flood. Community members waded through waist-high porter to salvage what little of their belongings they could, and they mourned their dead.

The brewery was eventually taken to court for the flooding, but after examining all the evidence, the court ruled that the flood was not due to negligence, but instead was an “Act of God.” The brewery and its employees were absolved from the incident, however, the brewery never quite recovered. Though the government waived the excise taxes the brewery had already paid on the spilled beer, the brewery’s brand would always be known for the flood and the death of eight people. In 1922, it shut its doors for good.